Updated: Date

Published: September 2015

Beyond death, a writer’s words live on

Memories of a special friendship preserved amid notations in books

By DAPHNE LAVERS

Writing from Toronto

Browsing through the bookshelves in my living room at the lake a couple of summers ago, I was looking for nothing in particular for a sunny-day, cottage-summer read. On one of the bottom shelves, I came across a strange and unfamiliar book I’d never read and knew I’d never bought.

The Life and Loves of a She-Devil, written by English novelist Fay Weldon, was a book I’d heard of years ago. I knew I’d never bought or borrowed that book, yet there it was, somehow, inexplicably, sitting in my bookshelf.

Curious and surprised, I sat down on the floor and began to leaf through the paperback. It is the story of a dutiful but unappreciated, long-suffering wife whose incremental rejection by her husband leads to a years-long, purposeful and eventually-successful journey of reinvention and, ultimately, a classic and definitive feminine revenge.

I turned to the inside cover page. There, in a so-familiar and definitive script, was hand-written a simple notation: “Erewhon.”

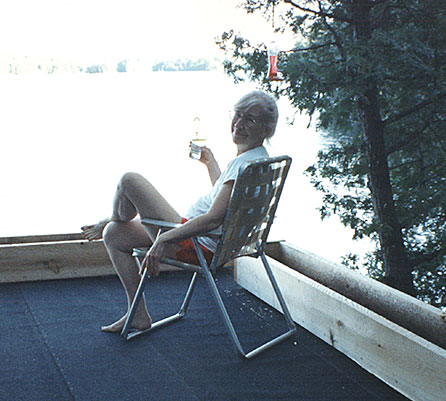

She-Devil was one of Nat’s books, part of the ever-changing library she had built up over the years at her wilderness retreat, Erewhon. As I sat on the floor, memories of Natalie flooded through my mind: the laughter, the jokes, the shared exchanges about friends, husbands, work, children – in Nat’s case – and sun-drenched, lazy days on the deck at Erewhon, built right out over the water….

Nat’s retreatNatalie Edwards – Nat to her friends and “Gnat” when she was feeling particularly mischievous – died on March 1, 2013, a year or so before I discovered She-Devil in my bookcase. Finding one of her books at my cottage in the North Kawarthas felt like a small, temporal gift; a reminder of her presence. Still keenly aware of the loss, I had also lost a number of other friends who had suddenly and astonishingly passed away within a too-short period of time.

Natalie, a writer, editor, an early-adopter computer whiz and attentive mother of five, lived for many, many years in Rosedale, one of the very tony areas of uptown Toronto, with her then-husband. But Nat spent entire summers, months on end, at her simple three-season cabin on Eel’s Lake. She called it Erewhon after the utopian book of the same name by Samuel Butler…a whimsical choice, as those who have read the book know that it’s more or less the word “Nowhere” spelled backwards.

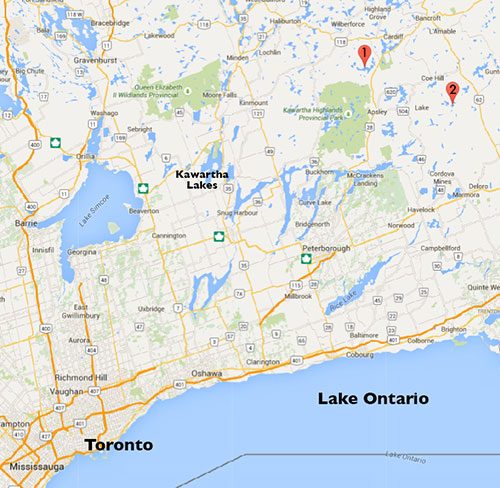

A young Natalie and her then-husband purchased two lots on Eel’s Lake in the 1950s when the province first opened the Kawartha area of Crown land to cottagers. Eel’s Lake is about 2 1/2 hours northeast of Toronto, an hour and a half north of Peterborough in the heart of ancient Canadian Shield rock. My own wilderness retreat is an hour further east, in the area called North Kawarthas, on a smaller lake called Lake of Islands.

I’ve discovered that the main cottage, which I and Nat’s friends always called “The Big Cottage”, was the original Erewhon, the first structure on the property where Nat spent summers with her five children.

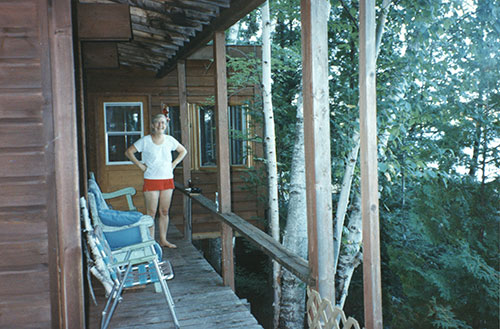

The small cottage on the adjacent lot, originally referred to as the guest cottage, “toofer” and finally “la mienne”, began life as a single, large, long room set crosswise on the hill, built on two-by-10s resting on concrete pillars or large stones. Meant originally, I think, as extra sleeping space for an overflow of guests, when through divisions and changes “the children” took over responsibility for The Big Cottage, Erewhon became Nat’s own place – at least to her friends and visitors.

Innovative Nattie, adventuresome Nattie, remarkable Nattie, added a 10 foot x 10 foot dining area on the front, with sliding glass doors onto a shingled outside deck and casement windows on either side. The dining room was atop an aging 10 foot x 10 foot room built originally as a waterfront boathouse, with a large wide front doorway that allowed one to leap directly into the water.

Nat also added a room of similar size on the hill side of the cottage, with its own small doors front and back, and a lake-facing deck. Built five or six stairs up from the main part of the cottage, this room served as M’lady’s bedroom and writing chambers.

The first meetingNat was, in a classic sense, more of a writer than a journalist per se, but it was journalism which provided her daily living. She wasn’t a journalist in the strict daily newspaper sense of ambulance-chasing or scandal-digging. For a time she wrote for the Toronto Star, as well as for international cinematic publications, had her own dining-out column in one of Toronto’s three big newspapers and was associate editor for Cinema Canada magazine. But she wrote mostly for broadcast and video production trade magazines. That’s how I met her, back in the mid-1980s, on a bus at the Calgary airport, heading for the Banff World Television Festival (now known as the Banff World Media Festival).

I had never been to the Banff festival, my previous professional incarnations having focused on communications technologies and cable television. But as the newly-minted editor of a national broadcast trade magazine, the trek to Banff was seen as one of the perks of editorship.

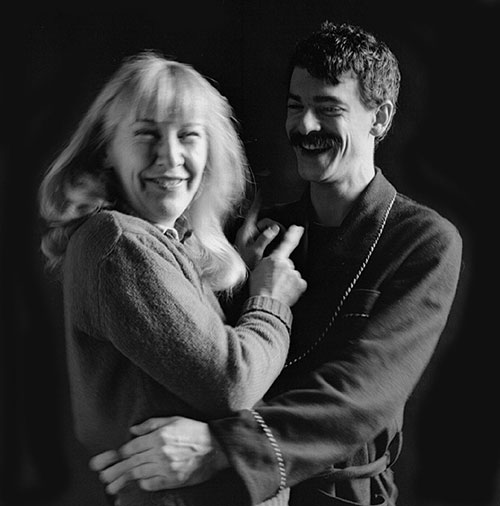

The festival sent charter buses to the Calgary airport to pick up journalists from all over the world and drive them into the mountains to the Banff Springs Hotel. As I walked down the aisle of a fairly full bus looking for a seat, I noted an empty aisle seat beside a petite, elegant woman with long fine blonde hair. She was studiously staring out the window and looking more like an artist or a hippie than the button-down suit and white-shirt business types we shared the bus with. I asked if the seat was taken; in her soft, articulate, honey-silk voice she said no and invited me to sit.

We didn’t talk much to begin with. After a while, following introductions and a bit of small-talk and professional-exchange conversation, Natalie allowed as to how she usually didn’t speak to any seatmate she found herself beside. Usually, she said, people were tiresome, tedious, talked the entire distance and were, most often, supremely uninteresting. I laughed out loud; I felt exactly the same way. We realized that neither of us was “that” kind of seatmate and that we might actually enjoy each other’s company!

I took Nat for a contemporary, such was the timelessness of her character, conversation and appearance. To my considerable surprise, I discovered she was about three decades my senior. She was, in fact, not only a mother, but actually, and fairly recently, a grandmother. I was astonished. And her now-altered position in “society” evoked stereotypes she found rather less than comfortable – at least for her – though her delight in her grandchildren was clear and evident. It was a brief mention, one that caught me quite by surprise, and the conversation moved on.

The days of the festival are somewhat vague memories at this point, with press conferences, screenings, announcements, press releases and people watching, deal-making and schmoozing.

One memorable afternoon, Natalie shepherded me to the screening room desk. She had attended the Banff festival for years and was an old pro at knowing what was where, how to secure the necessities of journalistic requirements and much else. We picked out perhaps four or five documentaries, movies and television programs, booked a screening room and snaffled Cokes and popcorn before settling in for an entire decadent afternoon of watching various new video productions – just the two of us. It was a wonderful and unique afternoon of laughter, of critiquing, and of learning a bit about the vast ocean of knowledge that Natalie Edwards carried about in her beautiful, blonde-haired, blue-eyed head. And thus began a remarkable and fascinating 25-year friendship.

Into the wildernessIt was some years later that Nat invited me to Erewhon for a few days. On my very first visit to Erewhon, decades before I had my own northern cottage but several years after first meeting Nat, I wasn’t sure my small four-by-four truck would actually make it through the wilderness.

A campground turn-off from Highway 28 north of Peterborough led down a one-and-a-half lane, barely-paved road. Nat’s intricate instructions then directed visitors to a turn onto a forest access road, a wide one-lane road from which one peered at the roadside trees for half-hidden signs. The forest access road turned into a single-lane gravel road, then into a barely-one-lane dirt road and finally into the almost invisible, overgrown donkey path to Erewhon.

Almost an hour off the highway, I finally found the grassy parking area off the donkey path marked by a tiny hand-painted sign “Erewhon”. I unloaded the stuff I’d brought and struggled down the steep, rocky wooded hill behind her “rustic” cottage, carrying luggage, coolers and whatnot, reaching the flat area behind her wood-sided cabin.

And there was Nat in a bathing suit, her long blonde hair tied back in a ponytail halfway down her back, wearing an old tattered sunhat and sitting splay-legged on her backside, on a brand-new deck finished right up to, and beside, the back door of the cottage. It was a wide, wooden square deck with two steps up to another brand new flat deck which served as a landing in front of the back door to her bedroom.

It was a hot summer day, and Nat had clearly been working away for some time. She stopped when I thumped down onto the new deck, looked up with her enchanting smile and said in that low, honeyed, beautifully-articulate voice, “Hello, darling, I’ve built a deck!”

And she had. Did all the measurements for a two-level deck, drew out exactly where it should go, figured out the steps up and the supports for the steps, along with the smaller deck off her bedroom; drove around the lake by car to the big hardware-lumberyard in the village of Apsley, ordered just the right amount of lumber and materials, helped the lumberyard guys (who floated the lumber across the lake from the far landing) to get all the lumber up behind the cottage, and then set about building it. Herself. None of her adult children were at the lake that week, or had been for several weeks.

And after laying out all the lumber, securing the framework and supports, she had parked herself on her butt most of the morning, tanned legs extended out in front of her, hammering nails into the boards between her knees. Carefully.

It was a big open two-level deck under the trees. Eventually, a roughed-in, waist-high tabletop held a washstand complete with mirror, wash basin and pitcher. A couple of wooden racks held drying bathing suits and towels; pails of water were there for rinsing bare feet covered in pine needles and dirt before entering the cottage. A clothesline strung from the cottage to the trees was added to the flat space, used for storing coolers, recycling and other such things.

A very special womanNat was special for a number of reasons, not the least of which, for me, as I often sensed on a personal level, was that she “felt like blood”. By that I mean that she felt like blood kin. We had the same hair – long, perfectly straight, light-coloured, and fly-away – though Nattie was far more skilled at putting her tresses into chic French buns and other elegant arrangements; the same light skin type, though Nat was rather more slender, petite, pale, refined; the same hands, with long, strong fingers and defined finger joints. We shared a Western background – she grew up in Saskatchewan while I grew up in Alberta – a camaraderie that others in this huge country don’t always seem to grasp. We had U.K. antecedents – both of us Scots and in Nat’s case, Irish as well; her maiden name was Harrington. Like me, she was also a writer, but she was focused both on writing and business, with far more experience and a gentle, elegant tenacity that served her well over the years.

Much to my delight, Nat and I were sometimes even mistaken for sisters, such were our physical similarities. One year, during another sojourn at Erewhon, one of her very beautiful small grandchildren looked up at us both standing side by side and with wide eyes, asked, curiously: “Are you two sisters?”

We both grinned. “We’re pseudo-sisters!” Nat answered, her eyes twinkling. And that’s what we remained, for years to come.

I wondered, that summer at Lake of Islands, whether Nat had inadvertently left The Life and Times of a She-Devil at my place; I thought to bring it back to the city when I’d read it and to return it to someone in her family.

But only a couple of months later, while again perusing my small library around the cottage, I found, again to my surprise, another book I’d never read nor bought.

An Actual Life by Abigail Thomas was a book I’d never heard of, a “coming-of-age story of a young woman and her new husband, both surprised by the turn of events that brought them together.” Inside the front cover in pencil, Nat had written, “Funny yes, but sad too, even getting tragic” with arrows indicating the book had originated with a friend Barbara, then had gone to Nat, and then, though I hadn’t added my name yet, to me.

More literary treasuresI became certain the act was deliberate and smiled when I envisioned her cleverly and surreptitiously bringing books from her bag in the guest room, on those few occasions she had come to visit, and slipping them into the bookcases in my living room when no one was looking.

One of the very first books ever brought to my cottage, more than a dozen years previously, was A Field Guide to Eastern Forests, part of aseries created and edited by renowned ornithologist Roger Tory Peterson (1908-1996). Long a staple of nature enthusiasts, outdoors folk, cottagers and hikers, it was also a staple of nearly every household in my family including my own grandparents who would answer almost all questions with the directive: “Look it up...” often in a Peterson’s Field Guide.

The Field Guide was of course, a gift from Natalie, and it was a standard in her home as well, growing up on the Prairies and at Erewhon. On the inside page of the Field Guide was a handwritten note: “At last, I’ve found the perfect house-warming gift for your cottage – an answer to (almost) all your questions…Love from Natalie, 2004.” The Eastern Forests field guide covers birds, mammals, trees, flowers, insects, reptiles, fungus – most of the subjects I’d queried Nat about extensively during my visits at her cottage.

And her knowledge was extensive. One of the many unique and eclectic friends she had brought to Erewhon one year was German, and had spent summers in the woods and fields of that country with her family, learning about everything wild and edible. She taught Nat about mushrooms; about Mother Nature’s trick of often creating two similar-looking mushrooms, one which was edible, the other which was poisonous. Nat learned well – I never caught on. She could wander through the woods around Erewhon and pick wild chanterelles, fry them up with vegetables and chicken, creating the most delicious dinners.

A wilderness retreatErewhon was a true wilderness cabin, with no power, even decades later when power lines eventually reached that part of the Kawarthas. Constructed of siding slats nailed over framing posts, it had no insulation, large screen-covered windows across the front of the cottage and a narrow deck in front of the windows with a door from the far end and another door beside the dining room.

Erewhon also had no running water. Nat kept huge jugs and buckets of water at the back door which were refilled from the lake several times a day for washing up. On the way into Erewhon, Nat would stop at a spring-fed pond where all the original cottagers stopped, to secure clean, fresh drinking water. The pond was fed by an age-old, fresh-water spring and had a small, convenient plank across one corner, thoughtfully placed there by the owner of the property for ease of communal water collection. In addition, Nat kept a large commercial 5-gallon water bottle with a manual pump mounted on top.

For heating, Erewhon had the old ski chalet standby, an orange 1960s-era acorn fireplace. An ancient propane stove and a single propane-fuelled lamp above the kitchen sink were the primary “mod-cons”. For decades, Nat used an antique ice box complete with the large steel box for the requisite block of ice to keep food cool, if not cold. These accoutrements provided the survival tools for her months-long summers.

She had an old-fashioned chamber pot – known laughingly in the old days as a “thunder mug” – in her bedroom. Guests were provided with flashlights for nightly treks up the short but fairly steep hill behind the cottage to the outhouse. On the wall of the outhouse, hand-written and mounted in a picture frame of Nat’s handiwork, hung a short poem by Gerard Manley Hopkins:

What would this world be, once bereft

Of wet and wilderness, let them be left,

Oh let them be left, the wild and the wet!

Long live the weeds and the wilderness yet.

One of the first things I did with my own northern retreat was to reproduce that poem and hang it right inside the front door, illustrated with cattails and a single ladybug. It was a touch of Erewhon at Lake of Islands.

Evolution of NatalieNatalie had a calm, quiet elegance, a Vogue-turned-hippie-turned-environmentalist knowledge, a personal and unique style of both dress and attitude, and a cosmopolitan world view tempered by experience. For a while, she worked at the United Nations in New York, as a newly-married young woman. She attended the Cannes Film Festival in France for years running and never missed the Toronto International Film Festival, both of which she reported on extensively. And she upended her life and moved to Vancouver to work in the film and television production industries.

Vancouver documentary filmmaker Peg Campbell wrote in Cineworks Beginnings – A Personal Chronology: In about 1979 “Natalie Edwards arrives from Toronto to set up a western branch of Canadian Filmmakers' Distribution Centre in Vancouver. CFMDC was started in Toronto by experimental filmmakers who wanted control over distribution of their work, and, frankly, to create the possibility of distribution for their films.”

She was a regular contributor to Playback, the upstart film and television trade magazine that became the de facto publication of record for the industry. And by that time, she had already begun to compile what was most likely the most comprehensive database on film and television production in the entire country.

Nat was that rare combination of both knowledge and wisdom. Decades before the current caution about aspartame, saccharine and other new chemical sweeteners, Nat had grown curious, done the research using original scientific data and discovered the studies that indicated this stuff is not at all good for humans. Her knowledge of mushrooms and other wild edibles, as noted, was fairly extensive. From the old remedies of ginseng tea to the more-recently discovered benefits of large doses of Vitamin C, Nat’s life included endless learning.

Nat was game for just about anything. I arrived one summer afternoon for what had by then become my annual precious few days at Erewhon and discovered that she had pondered, as usual, a totally-optional “work project” for us. She had decided that the 10 foot x 10 foot dining room addition on top of the boathouse should have a tongue-in-groove cedar ceiling. If I was interested and up for it, we would complete the ceiling. I was and we did.

Ceiling work is about the toughest and most demanding of indoor projects. I’d never worked with tongue-in-groove and had never worked on a ceiling in my life. I don’t believe Nat had either. Hands over your head, arms tire, fingers slip and shoulders ache. Fortunately, 10 foot x 10 foot is not a large space; between the two of us, taking turns on the ladder, we slid and shimmied and tapped that ceiling into place over the course of the afternoon. A finishing touch of quarter round around the joining edges to the wall finished it all beautifully – mostly. The very last one or two boards, we discovered, were simply beyond us; we couldn’t get them to fit, couldn’t get them into place no matter what we tried, and Nat finally conceded that she would persuade her eldest, a professional painter and contractor, to do those final two small boards. It was one of the toughest, most challenging, rewarding and fascinating projects ever.

But even more challenging was the year of the Findlay Fire Box, an antique wood cooking stove which had been the main source of heating and to some extent cooking in the Big Cottage for decades.

The Findlay Fire Box is well known to those of certain generations or those whose parents grew up in the Great Depression. It was a standard in the homes of Canadian pioneers, including one set of my own grandparents, long after their Manitoba home was outfitted with an electric stove, fridge and all the “mod-cons” we take for granted.

The Findlay Fire Box is a cast-iron stove, the bottom divided into two sections, one to feed wood into, the other for baking. The cast iron top surface had either two or four cast-iron burners, lifted off the stove by means of a hefty handle that fit neatly into the simple burner slots. You could feed wood or any combustibles into the fire box, and it would keep the room warm all day, including a kettle for hot for tea at any time.

The Findlay Fire Box in the Big Cottage had eventually been replaced by an air-tight stove. The fire box had been moved out of the Big Cottage and a few feet along the pathway that led to Erewhon. But now Nat wanted it in her cottage.

When I arrived that summer, there it was, sitting on the slightly-sloped hillside in the woods on its solid cast iron legs, weighing probably close to 300 pounds. Nat figured that if I was up to the challenge, between the two of us, we could manoeuvre it bit by bit over to Erewhon. And I figured we could too.

Now Nat was about 5 feet tall and perhaps 100 pounds soaking wet. I’m about 5 feet, 4 inches, and at that time I weighed about 110 pounds. By August, after months at Erewhon, Nat was in fine form from trekking up and down the hillsides and to the lake, hauling water and firewood. I was in fairly good shape, and fully in for this ludicrous task. We laughed aloud, wondering if we could actually pull this one off.

Inch by inch, edging and turning, tipping the fire box first on one foot and then on another, we tugged and hauled, and pushed and pulled for half the afternoon. And at the end, we had it; up on the back deck of Erewhon, close to the back door. She had already arranged for a long-haired, motorcycle-riding, jack-of-all-trades neighbour to cut the hole in the back wall of the cottage for the right-angled chimney exhaust for the chimney pipe and to connect up the fire box. She was delighted.

Tattoo with a messageWhile Nat could move equally well among the circles of the high-brow, cosmopolitan elite as well as homeless, street people, she also had what some might call her own peculiar determinations and whimsies. One of the first I witnessed was one summer at Erewhon when she hosted one of her grandchildren who wanted hot pink streaks in his jet black hair.

“Of course!” Nat agreed at once, deciding immediately to do the same with her own blonde-white, long locks. It looked gorgeous on both of them, but turned heads in Toronto. The pink was a brilliant, electric pink and Nat’s streaks, limited in number, were unmistakably eye-catching.

And then, in 2001, when she was in her early 70s, there was the tattoo. Nat had long conversations about transplants and the need for organ donors, about the state of Canadian medicine and simple things everyone could do that could make a difference. We had also discussed the idea and she put together a proposal for a magazine article on the possibilities.

“A few years ago during an email conversation with a West Coast pal,” she wrote, “the subject of organ donation came up, and as we worried over the need for more available organs and discussed the problem with various friends, gradually a concept formed for a tattoo that would make our position on the subject clear to those dealing with our bodies, and couldn't be lost or denied. The final plan involved a design using the three green recycling arrows surrounding a red cross on which our blood type would be noted.”

Nat wanted a permanent fixture on her skin that would make it clear, when the time came, that anything of her corporeal self that might be of use to anyone else should be so used. We’d discussed the idea and came with the notion of a tattoo kit for prospective donors, which would include definition of blood type.

“On Easter Monday, almost on a whim, I found myself describing this to the clerk at Way Cool Tattoos, a tattoo parlor on Queen (Street) West (in Toronto). A few days later I was 'getting inked.' I now wear just such a tattoo on my upper arm. I'd like to tell that story,” she wrote in her magazine proposal.

She did end up telling the story about her shoulder tattoo – a green recycling triangle with her blood type, “A” inked in bright red in the centre – for an online writing group to which she belonged. That story in Nat’s own words is reproduced as a sidebar to this article.

More discoveries and treasuresStaying in the wilderness for periods of time with someone who’s a natural in accommodating the absence of “mod-cons” teaches you invaluable lessons that come in handy when those modern conveniences we take for granted – power, heat, running water et al – are suddenly gone.

My wilderness retreat is very different from Nat’s. Constructed of 8-inch x 8-inch solid pine beams, it is a four-season, fully-insulated home with a foundation sunk into Canadian Shield bedrock. As at Erewhon, the wilderness is right outside the door on Lake of Islands – thick old growth forest on the numerous islands dotting the lake, and massive pine trees on the south shore.

On her first visit, Nat observed that the absence of giant pines on this north shore must have resulted from a forest fire – an astute observation eventually confirmed by long-time area residents. Running water, indoor plumbing, fridge, stove and fireplace make literally for all the comforts of home.

These are very different living spaces sharing the same appreciation of silence, books and solitude. But when the power goes out, as it does more often than one would imagine, all the conveniences of modern day life go out the window. And if you’ve learned to live as Nat did, then you can get along almost as well as Nat.

Although I don’t have propane, I have flashlights and candles for light. My air-tight fireplace provides enough heat to warm the cottage entirely and to heat water for washing and dishes. Although I never did put in an outhouse – a prudent move I had originally planned – buckets of water from the lake will flush the toilets and provides a close source of water for kitchen tasks.

And curiously, when the power goes out, in the absence of electricity I find myself living more in tune with the seasons, as Nat did at Erewhon. While not quite rising with the sun as she did, but close enough, I often retire for the night shortly after sunset, with candlelight for evening reading.

And I discovered the cleverness of the heavy velvet curtain Nat had hung over her short staircase close to the fireplace, leading up to her own bedroom. The heat rose all evening, warming her bedroom, and when the embers burned low, closing that velvet drape kept her bedroom warm and comfortable. I understood when I saw Nat’s cleverness why the old Scottish castles (and English too, no doubt) were hung with heavy tapestries on both walls and windows. I followed suit, sewing heavy velvet drapes for the windows in the bedroom at Lake of Islands. They keep the warmth inside on cold nights, and keep the bedroom cool during hot summer days.

The summer I first found the book from Nat in my library, I subsequently discovered there were even more literary treasures my dear friend left behind for me to find.

I discovered The Irish by Sean O’Faolain, a paperback on the history and mindset of the Irish, of which Nat’s heritage was in large part comprised, and inside the front cover, simply “N.E. 2000” – Nat’s initials and the year she read it. Then The All-True Travels and Adventures of Lidie Newton by Jane Smiley, a novel about the pre-Civil War American south, reflecting Nat’s partial American heritage and knowledge. The inscription inside the front cover read only Nat’s name, Toronto address and a note to herself - “Feb. ’99, read again – some day!”

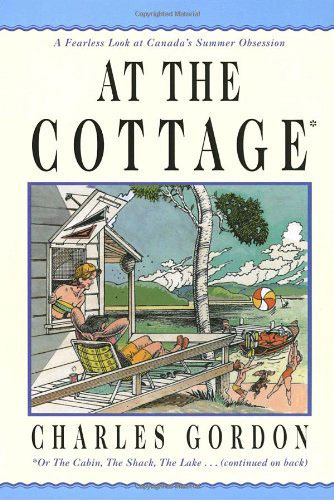

And another treasure, At the Cottage by Charles Gordon, the consummate recital of the joys of cottaging, but the inscription in this book is: “Here’s looking at summer, 2000! From Christmas, ’99. Hope you enjoy. Love Murray.” I caught my breath in surprise; Murray was Nat’s long-time, one-time husband, a university professor from whom she had separated 30 years prior. Murray had moved to the West Coast and they had over the years worked into a different relationship, on good terms and as good friends, with shared memories.

And since those first delightful discoveries, there have been several other surprising treasures I’ve discovered among my books; The Road from Coorain by Jill Ker Conway, a story and biography which starts in Australia and ends in the U.S., with an inscription to Natalie from one of her oldest and best friends, Nadia. It was marked “Christmas, 1994, for the long trip east.” Fascinating, adventurous Nadia, one of many of Natalie’s friends who had spent much time at Erewhon with Nat, had died at an unfairly young age only a few years prior.

There are two by Mary McCarthy, The Group and The Company She Keeps. Also Mordecai Richler’s Solomon Gursky Was Here.

The Lonely Plough by Constance Holme, I believe is the story of an English farmer, though I haven’t yet read it, with the inscription, “Love Aunt Winty, Aug. 1953.” I knew from long-into-the-night conversations that Nat had American relatives who summered in the mountains in the Eastern U.S. and who led adventuresome lives for ladies in the wilderness.

Then I discovered Lillian Hellman’s Pentimento, a book I had read decades earlier about reminiscences and brilliant observations of the playwright and novelist. I thought the paperback edition in my bookcase was mine, but I pulled it out, just to see. It wasn’t; there in Nat’s writing was a note: “June 1999 – A treat to re-read, especially now that I am continually writing and so much more aware of her discipline, ease and natural gift of story-telling – seems to just hum along…. N.E.”

Each time I found another treasured book Nat had quietly and thoughtfully slipped unnoticed into my bookcases, it was a gentle, heart-warming reminder of an exceptional person who had once been a large part of my life. It’s been several summers now since Nat died, and I continue to find small treasures she pondered, considered, and slipped into her suitcase for her visits to Lake of Islands.

At the end of the summer of 2014, another treasure hidden this time in the loft bookcase, an old, unfashionable and now politically-incorrect novel, Uncle Remus, His Songs and His Sayings by Joel Chandler Harris, one of those classic children’s books we had both grown up with. Originally copyrighted in 1880, this edition is 1935, one of many numerous editions. Nat believed both in political correctness – in the sense of there being no need to offend or insult gratuitously – but also, as a writer herself, in the almost-sacred integrity of original literature. This ancient hardcover and now politically incorrect historical novel, the page edges frayed but the binding intact, has a simple personalized Natalie bookplate, a stylized “Ex Libris” with her full name professionally printed in the same beautiful teal blue.

I realize, as did Nat, that things are only things and often purposeless, physical accoutrements everyone can mostly live without. So be it, but there are other treasures from Nat both at my cottage and at my place in Toronto that evoke both memory, knowledge and smiles: a brass Cape Cod fire lighter – a brass pitcher which held coal oil, with a brass-handled ceramic ball used in the old days to easily and quickly light logs in big old stone fireplaces; a very warm and soft, old, thigh-length sweater, given to Nat by one of her friends, worn for years and then brought to Lake of Islands to keep me warm on cool fall evenings.

In the early years of my visits to Erewhon, Nat had fished out of the lake a particularly beautiful piece of driftwood, an ancient interestingly-shaped piece of driftwood she knew instinctively I would admire that sits on top of my bookcase in the city. Even more precious was learning her practised knowledge of how to run a home without running water or power; but perhaps most of all, the treasure trove of books that she scattered about my cottage on Lake of Islands, knowing that eventually my curiosity would lead me to find them all.

The rule of threeThere are still other treasures, incorporeal, and gifts from Nat, one of which is “the rule of three.” She learned the rule from her father, she told me, an agricultural geneticist whose workplace/playground in the 1930s was Saskatchewan, where he practised his knowledge in the ancient real-life custom of cross-breeding plants to enhance beneficial traits.

Nat was building a fire one night at Erewhon in the acorn fireplace, and stacked three small logs in a tee-pee formation with kindling from the forest outside.

“The rule of three,” she said mysteriously, that enchanting half-smile accompanying a glance in my direction. “And what’s that?” I asked, of course. “It’s a way of doing things that makes most things easier,” she said, “in a whole bunch of areas.” The three logs in formation with the kindling below caught fire almost at once, and began to burn perfectly.

She drew the mesh screen across the front of the fireplace.

“It works in many, many circumstance,” she said, “Just watch when you’re doing things.” And in fact, I have. Building fires is only one; folding sheets, pillowcases, tea towels is another. Planting daffodils or even small fir trees I’ve found is a third. Even friendships can work well with a trio of friends – though as Nat wisely observed, it does not often hold up well in intimate relationships!

Nat’s philosophy most often emerged in stories and she joined the Storytellers Group, a collective of people who meet, gather audiences and tell stories, an oral tradition that imparts context and meaning far beyond the written word. One of Nat’s wisest philosophies, which she shared with me, is about the existence of basically two kinds of people in the world; we examined and, in a way, deconstructed, the meaning and personification of both.

One kind of person stands, looks deeply and delighted into your eyes, arms open, palms up and says, heartfelt and warmly, “There you are!”

The other kind of person stands, looks deeply and delighted into your eyes, arms open, palms up and says, heartfelt and warmly, “Here I am!”

These are two opposite life views, opposite world positions, opposite personal presentations to the world. From these two presenting positions, two divergent worlds vie with each other in our lives.

“There You Are” (TYA) first acknowledges the existence and instantly, the presence, of another; subsequently says, unarticulated, I’m delighted to see you, to be with you; and thirdly, again, unarticulated, the world stops for this moment while you are here and recognized.

“Here I Am” (HIA) acknowledges first one’s own existence in this instant; calls attention to one’s immediate presence, and demands recognition of that presence.

Subsequently, TYA says, also without words, Talk to me. Tell me about you. I am here, I am ready to listen and I am pleased with your presence.

The unarticulated subtext of HIA is a demand: “Notice me and pay attention to me!”

A few medical issuesAn affinity for books, for culinary explorations, for climbing across the rocks to get to the water for a swim, a long-standing curiosity about many different things, a similar background of growing up on the Prairies, and the fact that we were both writers, continually strengthened a decades-long friendship.

But she was a different generation and several years ago began having some minor – in her words! – medical difficulties. She had some kind of heart valve problem since she was a child. Only now, in her later years, it began to be bothersome, especially with the exertions required to live alone at Erewhon.

As she was a senior – although ageless to me – several doctors refused to do the operation that would correct the heart valve problem that now made her breathless on occasion, a condition she found most irritating. She found the refusal by physicians to do the corrective surgery even more irksome – one of the aggravating examples of ageism in an evolving society – and continued her search for a doctor who in effect wouldn’t disqualify her from such surgery because of her age.

She found one; the surgery was conducted at one of the big, well-known hospitals in Toronto. It was lengthy and although successful, there was some issue about an incorrect procedure during the surgery that necessitated more surgery the next day. It was the second round that was most difficult and most physically destructive. Nat was basically in a coma for about six weeks. Against all odds, she made it.

I went to visit her in the rehabilitation hospital where staff were teaching her what her life would be like from then on; not crossing her legs (in a typically lady-like fashion!) because that could cause blood clots; recovering her appetite; relearning some fine motor skills.

I walked into the room filled with both patients and staff all working studiously at lunch tables, with walkers, with various paraphernalia of recovery. On the far side of the room Nat almost immediately saw me; her face lit up, as I’m sure did mine. I walked across the room, we hugged and sat down.

“I wasn’t sure you’d make it, Nat,” I said gently. Her clear blue eyes gazed back at me with kindness, unflinching honesty and delight.

“Neither was I, Daph.”

But she did.

She could not, however, drive anymore. Her ancient Buick which she named, of course – Bucky - was now parked behind her Cabbagetown flat which she had rented after finally selling the big house in Rosedale. Years ago, I’d driven her to Ottawa, to purchase Bucky second-hand from a mutual friend.

“I always wanted a Buick,” she said by way of explanation. She’d had small compact cars which she kept for years, and at last, wanted to finally drive a big, comfortable North American car. She drove Bucky for years, back and forth to Erewhon, and all over Toronto.

But now, she could no longer drive. One of the peculiar side-effects of heart surgery, Nat told me, was that many times, people end up with damage to one optical nerve. Sometimes it’s minor damage; sometimes it’s total blindness in one eye, something she’d never heard of and was a tad miffed she hadn’t been told beforehand. But true to form, Nat never obviously carried a grudge and also true to form, Nat found the impossible humour in the situation.

“I see double now,” she said, “which is irritating when you go to reach for something. But I went to the ballet and instead of one prima ballerina on stage, I saw two! I saw two of everything, the stage was filled with dancers and it was quite beautiful!”

She was also, strangely, diagnosed with Parkinson’s, a disease neither of us knew much about. “Paralysis agitans,” the Latin designation, “is a relatively common malady which produces such a striking picture that almost any observant person can recognize it at a glance,” according to the 1960 edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica. “The stooped posture, the slowness of movement, the carriage of the arms in front of the body, the short-stepped festinating gait, the fixity of facial expression and the tremor of the hands are the characteristic signs.” But most significantly and thankfully, “The senses and the intellect are preserved.”

Finally, the nimble, agile, risk-taking Nat was forced to move more slowly and more carefully. Describing to me what she knew of the disease, she smiled, characteristically, as she demonstrated how those with Parkinson’s will invariably raise their arms and hands to waist-level, almost as though fending off unseen obstructions.

“Almost like the small raptor dinosaurs in Jurassic Park, the velociraptors, with their hands, claw-like, ready to seize unsuspecting prey!” She immediately dropped her arms to her sides. And from then on, Nat’s walk became, for us, her “raptor-walk”, and yes, even that was cause for laughter.

Her world shrank only somewhat after her recovery. She continued with her Boxing Day all-day parties; she would go to Erewhon when she could be driven and have company; and she continued with both her book club and her volunteering at the nearby Riverdale Zoo gift shop.

After some time, though, she confessed, laughing and amused as usual about the situation, that she was now having trouble with simple arithmetic – a necessary ability when working in a gift shop. She laughed with the youngsters who helped her do basic addition and subtraction – they never knew, of course, that this was the woman who compiled the most comprehensive, computerized database in the country on film and television production long before any of them had ever used a computer! To Nat, it was not ironic, it was hilarious.

But it was years later that Parkinson’s disease took Nat, who died peacefully on March 1, 2013, surrounded by family and friends in her home and with her cat, Beau, asleep on her feet. Out of the country, I missed her by one day. I’d seen her at Christmas, bringing my shortbread and probably Christmas cake for our usual warm, wonderful and marvellous chats. By then in her 80s, she only seemed to move a bit more slowly, taking the stairs one at a time and holding onto the handrail then. Her coterie of angels, a group of women from the Philippines, had changed shifts from daytime to day and evening, and then to 24 hours as Nat imperceptibly declined. They were all friends, serendipity that worked like magic, and came to know and love Nat like all of her other friends and family.

A week or two later, The Gathering was held at Nat’s flat in Cabbagetown, a huge collection of family and friends, of children and elders, of artists and writers and business people and actors, exactly the same kind of come-and-go that Nat held every year on Boxing Day and in earlier years, on May Day to celebrate spring.

There were, I noticed, a few surprised glances and double-takes when I walked in; our physical resemblance was more pronounced than even I had guessed. Nat had, some time earlier, put together a booklet that she called Pseudo-Sisters, photos of Nat with all her treasured women friends over the years which was out on a side table along with a host of treasures and memories. On the cover, though, was a photo of Nat and me, looking almost as though we could be twins.

(A year or so later, one of her daughters gave me one of the most treasured of gifts; she wrote to me that I was the sister Nat always wished she’d had.)

And I read the free-form poem that has become a touchstone in my family when yet another soul passes from here to beyond, and hope, somehow, there is some truth in this.*

I am standing on the ocean shore

Watching…as a ship set sail

She is an object of

Beauty, strength, dignity, and truth.

I watch

Till soon she is on the horizon and passes from my sight.

Gently, softly, someone comforts me and whispers

“There, she is gone.”

“Gone?”

Gone from me only.

She is as she was

And

She is as she will always be…

At that moment, when someone whispers,

‘She is gone’…there were others

On the other side, on the far-off shore

Waiting to take up the glad shout…

“There, she comes!”

Editor’s Notes:

A variant of this poem, which compares the experience of death with the voyage of a magnificent sailing ship leaving the port of life for that of the celestial afterlife, has appeared under different titles with varying attributions over the years. It is most often attributed to Henry Van Dyke, (1852-1933), an American Presbyterian clergyman who was an accomplished author, poet and literary critic, under the title, A Parable of Immortality.

But a version of the poem titled, What is Dying? was published on July 13, 1904 by the Northwestern Christian Advocate weekly newspaper which credited it to Luther F. Beecher, a New England clergyman who died on November 5, 1903 at age 90. Later in 1904, two other publications published the poem with attribution to Reverend Beecher: Northwestern Christian Advocate on July 13, 1904 and Religious Telescope on August 21, 1904. In March 2012, Google Books digitized a book titled, 52 Things Sons Need from their Moms, which reproduced that version of the poem which had appeared in the Northwestern Christian Advocate in 1904 with attribution to Reverend Beecher.

For those wondering, Natalie’s wish that upon her death parts of her body be used for patients in need of transplants was never fulfilled. Part of the reason was her illness and the fact that she died at home, which would have caused time delays in harvesting her organs.