Updated: April 2017

Published: November 2013

Canadian technology dominates world market

Matching bullets with crime guns is both a science and a money-maker

By Warren Perley

Writing from Montreal

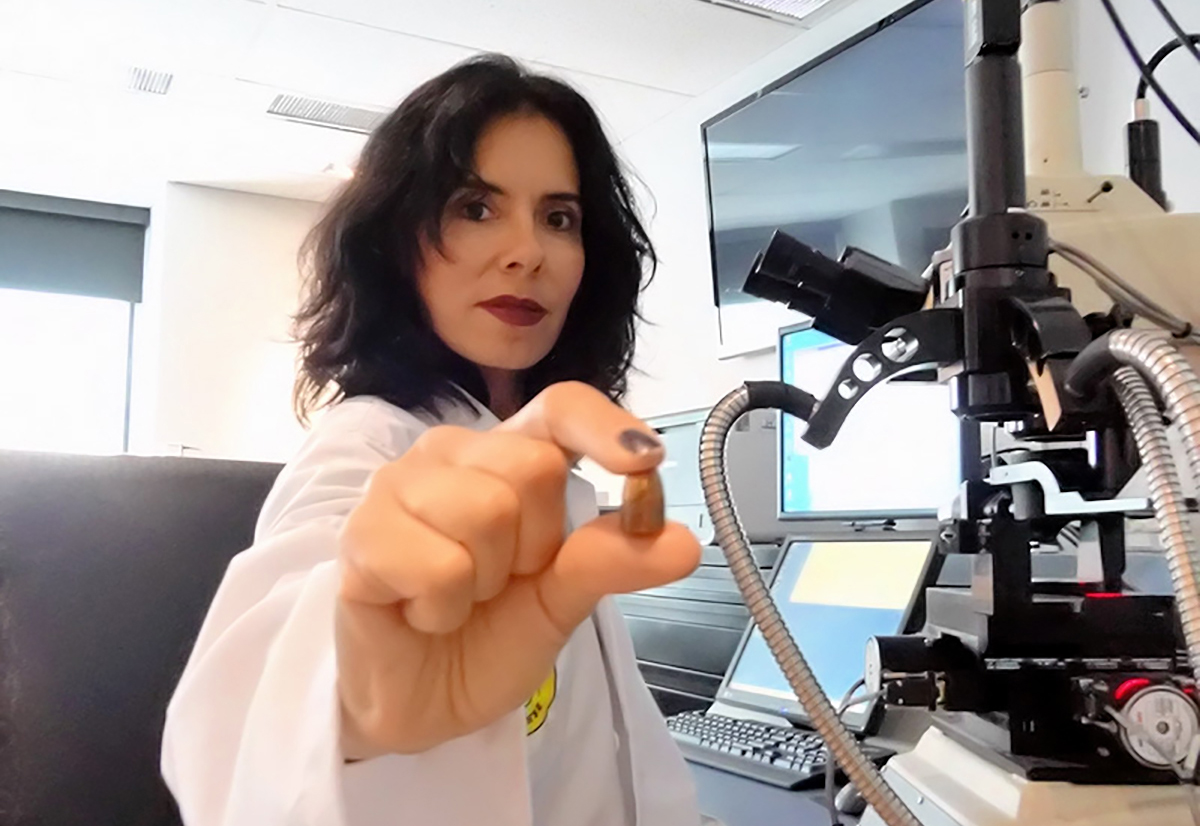

A jar of bullets on her desk is a tipoff to Perla Jasso’s passion for her career training police forces around the world in the use of a cutting-edge, digital technology used to solve gun crimes.

Jasso, a naturalized Canadian born in Mexico, works for Montreal-based Forensic Technology, which developed the technique known as the Integrated Ballistics Identification System (IBIS). Matching the unique markings of bullets and cartridge cases found at crime scenes with the guns used to fire them, it has evolved over the last two decades into a game-changer in the battle to arrest and convict violent criminals.

Crimes which used to go unpunished are increasingly being solved as police forces around the world, with technical support from Forensic Technology, use IBIS to create databanks containing the unique markings of crime-scene bullets and cartridge cases which can then be matched against guns that have been test-fired by police.

The key is an ever-expanding database as police in about 70 countries use the IBIS system to share data among themselves and — increasingly — with Interpol, which held a seminar in Montreal in May 2013 to promote IBIS and the expansion of such data-sharing.

Privately-held Forensic Technology says it has over 95 percent of the ballistics identification market worldwide with annual sales of $50 million.

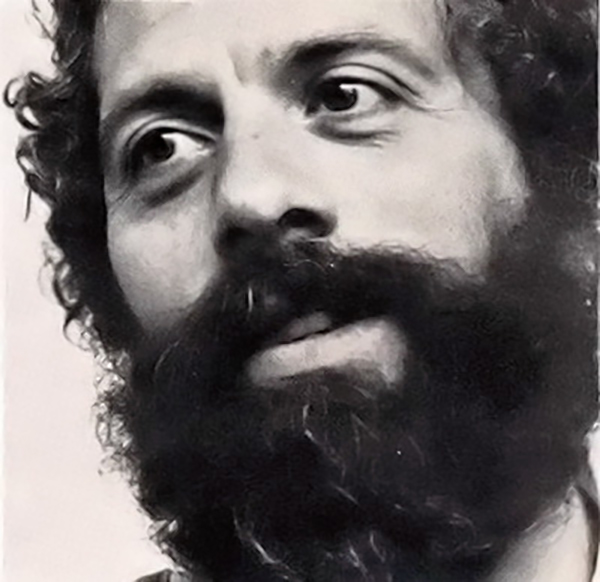

Jasso likes to relate to visitors what she calls “noble stories” about how her company’s technology has brought a measure of justice and closure to families of shooting victims. Victims such as Argentinian singer, songwriter and philosopher Facundo Cabral, who was shot dead en route to La Aurora International Airport in Guatemala City from where he was supposed to fly out in the early morning hours of July 9, 2011 after performing at a concert the night before.

Cabral’s white Range Rover was attacked at 5:20 a.m. on Liberation Boulevard, a normally busy thoroughfare which was deserted at that early morning hour. Gunmen wearing bullet-proof vests and sporting AK-47s attacked in three vehicles, peppering the Range Rover with at least 20 bullets, killing the 74-year-old Cabral and wounding his agent David Llanos and Henry Fariñas, a Nicaraguan concert promoter and nightclub owner.

A vehicle carrying bodyguards was unable to prevent the attack, which authorities later determined was aimed at Fariñas, who was wounded. Guatemalan prosecutors alleged that the hit on Fariñas was ordered by Alejandro Jimenez Gonzalez, the Costa Rican head of a gang of drug smugglers, because he believed that Fariñas, who had laundered money for him, had stolen one of his cocaine shipments. Fourteen months later, Fariñas was convicted of money laundering, drug trafficking and organized crime by a Nicaraguan judge. Meanwhile, Jiminez, also known as Palidejo, was being held in a Guatemalan jail awaiting trial for Cabral’s murder. He also faced charges for drug trafficking and money laundering in Nicaragua.

InSight Crime, a website supported by the non-profit Open Society Foundations founded by American billionaire philanthropist George Soros, speculated in June 2012 that Jiminez might also be the name blacked out in a U.S. indictment issued by a New York court in 2006 for drug trafficking charges in America.

Gabriel Maldonado Soler, a former Mexican federal police officer and head of the Los Charros gang that is believed to have killed Cabral on orders from Jiminez, was sentenced in Nicaragua in 2012 to 30 years in prison for drug trafficking, money laundering and other organized crime activities. Fourteen of his gang members received sentences ranging from six to 30 years.

IBIS technology solves crimesCarlos Enrique Gonzalez, who manages the IBIS system for the Institute of Forensic Sciences in Guatemala, says the firearms captured by police when they arrested Cabral’s killers were tested-fired and led to matches with bullets used in Cabral’s death, as well as numerous other crimes in his country. Guatemala has a population of 14 million with about 5,000 to 5,500 violent deaths annually, 85 percent of them caused by firearms.

“Facundo Cabral’s murder was like the key that opened the door to nab the [criminal] organization,” he told an Interpol seminar held in Montreal in May 2013. “…It is good for Guatemala at an international level to know that crimes get solved, which before IBIS [2010] was difficult; it was a dead end, we had no clues.…If our authorities had purchased IBIS between 2000 and 2002, I don’t think we would now have 5,000 deaths a year.“

Close to 20 percent of his institute’s annual budget has been invested in buying and maintaining the IBIS system, he said, with some critics having questioned why such a large percentage of disposable income was being used for such a specific program. The results, he said, have “completely satisfied” both him and his critics that they invested “in something which is state-of-the-art technology, which is helping and giving us hope…to build a more peaceful society.”

The international scope and impact of drug trafficking, as illustrated by the Cabral case, is another reason why Forensic Technology’s IBIS is so effective when international police forces are able to share ballistics data via Interpol.

“We bring justice to mourning families who otherwise would not have found it,” Jasso told me in an interview, referring to her company’s crime-solving, “nano-focus” technology, which can examine bullet details as small as one millionth of a millimeter in size.

When fired, every gun — manufactured anywhere in the world — leaves unique microscopic markings on the surface areas of bullets and cartridges. Called “toolmarks”, they are caused by the passing of bullets through the firing chamber and barrel or by the striking of the cartridge case by the firing pin, extractor and ejector. This ballistic signature is similar to a human fingerprint.

There is a better transfer of markings on cartridge cases, which are made of brass and get less damaged in the firing process than lead bullets, which are encased in copper jackets. But it is increasingly difficult to find cartridge cases at crime scenes because some criminals, who have become aware of such incriminating evidence through the CSI shows, often take the time to collect their spent cartridge cases. In some cases, Jasso told me, shooters even attach bags to their guns to catch the cartridge cases as they are ejected.

The Forensic Technology process works as follows:- Bullets or cartridge cases which have been recovered from a crime scene are scanned in high resolution into the IBIS system.

- A powerful server employs a mathematical algorithm to extract unique signatures from the bullets or cartridge cases.

- A correlation server compares all bullets and cartridge cases recovered from a crime scene with those test-fired from various seized weapons to see whether there is a match.

- Firearms examiners, also known as ballisticians, then examine under a microscope the Top 10 or Top 20 probable matches to see which one is the closest.

The IBIS technology has been endorsed by the International Association of Chiefs of Police, an organization over a century old representing 20,000 law enforcement professionals from 100 countries. Aside from the speed of the system in clearing backlogs by correlating pieces of evidence in hours rather than years, police management likes the system because less highly-trained (and less highly paid) technicians can operate the computers and present the most likely matches to more highly-trained and higher-paid firearms examiners who make the final call on whether there is a match between munitions and firearms.

Ammunition made by different manufacturers won’t produce a 100 percent match, but it is usually close enough for courts to accept it as forensic evidence when presented by a qualified firearms examiner. Once bullet and cartridge case details are scanned into the computerized database, it takes about four hours to correlate one million exhibits — bullets and/or cartridges cases — to determine whether there is a probable match between them and munitions from guns which have been test-fired by police. Working manually with a microscope, — which is the way such ballistics work was done from the turn of the 20th century until Forensic Technology brought their computerized technology to the fore 20 years ago — it would take one firearms expert four lifetimes to examine half that number — 500,000 — exhibits.

Bulletproof and BrasscatcherBullets are more time-consuming and complex to image than are cartridge cases because it’s rare that you recover a pristine bullet at a crime scene. Officials of the company — incorporated as Forensic Technology in 1992 —first developed a system of scanning and identifying bullets only. They trademarked the system as “Bulletproof”. In 1994, the company developed a similar system to scan and identify cartridge cases, calling it “Brasscatcher”.

Before Forensic Technology’s computerized database system, police firearms examiners could do nothing with bullets recovered at the scene of a crime unless investigators also happened to find the firearm nearby. Then they would test-fire the gun and compare the markings on the spent bullets with those recovered from the body of the victim or from the crime scene environment.

But with the encouragement of Forensic Technology, police forces in countries around the world have quietly been building their databases for the last decade, test-firing guns seized during routine arrests and storing the results in IBIS databases which are increasingly being shared by police forces across provincial, state and national boundaries.

The company’s first and largest client — the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) — came aboard in 1993 and now manages over 130 Forensic Technology systems throughout the U.S., most paid for by it. Their system is called the National Integrated Ballistics Information Network (NIBIN) and contains two millions exhibits. The only states which don’t have their own systems are Maine, Vermont, New Hampshire, Kentucky, North and South Dakota, as well as Montana.

Of the approximately 130 NIBIN labs in the U.S., between 15 and 20 belong to major cities, including the largest one owned by the New York City Police Department. The Boston Police Department also has its own NIBIN lab and is known to make heavy use of it.

The extensive use of the NIBIN system in Massachusetts may explain why police there were quickly able to match a gun seized in a car accident near Springfield, Massachusetts on June 21, 2013 with the killings of two young men one year earlier in a drive-by shooting in south Boston.

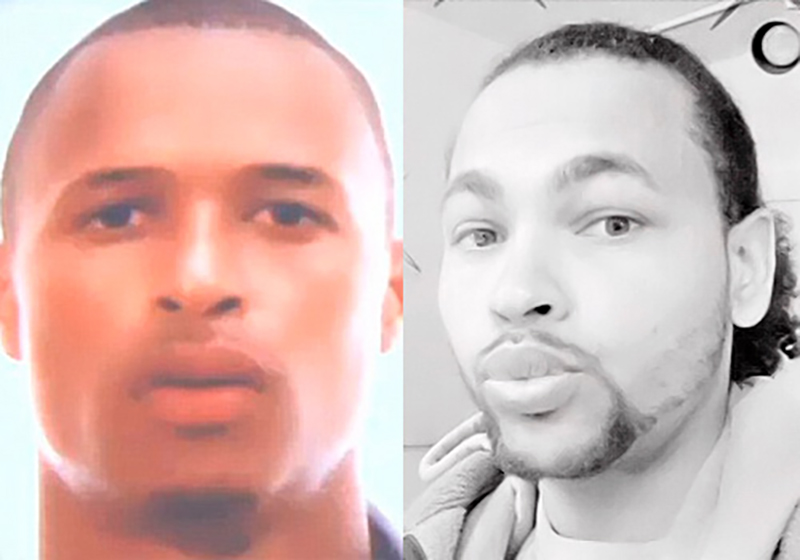

The shootings at 2 a.m. on July 16, 2012 left Daniel Jorge Correia de Abreu, 29, and Safiro Teixeira Furtado, 28, dead after they reportedly got into an argument in Cure Lounge, a south-end nightclub in Boston’s theatre district, with a group that included New England Patriots tight end Aaron Hernandez.

As Abreu drove away from the club in his BMW with Furtado in the front passenger seat, a silver or grey SUV with Rhode Island license plates pulled up next to the car and opened fire, according to witnesses, police said at the time.

Nobody was immediately charged in the case, but in early September 2013 “multiple law enforcement sources” told WTIC, the Fox television affiliate in Hartford CT, that police had surveillance footage from the club showing Hernandez, 23, with the two men who were later shot.

The case heated up again on June 21, 2013 when Jailene Diaz-Ramos, a 19-year-old woman who comes from Hernandez’s home town of Bristol, Connecticut, was involved in a multi-vehicle crash on I-91 near Springfield, and police found a .38-caliber Smith & Wesson Model 52 semi-automatic pistol in a black briefcase in the trunk of her car. Diaz-Ramos, who faced three illegal firearms charges in the case, told police that a football player, known by the nickname of “Chicago”, left the gun in her car.

Gun tied to killingsMassachusetts State Police tested the gun and found it matched the bullets which killed the two men in south Boston in July 2012, according to television station WSHM, the CBS affiliate in Springfield, which reported this in August 2013. The NIBIN system developed by Forensic Technology is the only computerized system used by the Massachusetts State Police to tie bullets and guns to crime scenes.

Neither the Massachusetts State Police nor the District Attorney’s office in Bristol County, which handled the Hernandez investigation, would go on record to answer a series of questions submitted by BestStory.ca.

Hernandez was charged with the first-degree murder of semi-pro football player Odin Lloyd on June 17, 2013 near Hernandez’s home in the Boston suburb of North Attleborough. He was arrested and jailed without bail on June 26, 2013. He pleaded not guilty.

The murder weapon in the Lloyd homicide, believed to be a .45-caliber Glock pistol, was never found. But given that police had a definite match via the NIBIN system between the .38-caliber Model 52 pistol seized in Springfield and the double homicide in south Boston in July 2012, they concentrated their efforts to build a case against Hernandez for the Boston shootings.

Fox 25 TV in Boston aired an interview on October 1, 2013 with one of three passengers wounded in the back seat of the BMW shot up in Boston on July 16, 2012. The unidentified man, whose face was not shown, told the Fox 25 reporter that he recognized Aaron Hernandez as the gunman in his case after he saw media reports of Hernandez’s arrest for the shooting of Lloyd on June 17, 2013.

On May 14, 2014, Hernandez was indicted for the murders of Daniel Abreu and Safiro Furtado by a grand jury, which heard evidence from the witness interviewed by Fox 25 TV and from Alexander Bradley, a former colleague who claimed that Hernandez shot him during an argument in February 2013, leaving him blind in one eye.

The indictment against Hernandez alleged that he and Bradley followed Abreu and Furtado after they left Cure Lounge on July 16, 2012 and pulled their SUV up next to the victims’ BMW at a nearby stop light, at which point Hernandez opened fire with a .38 caliber Smith & Wesson revolver. In exchange for immunity from prosecution, Bradley, 34, testified that he was driving the SUV, with Hernandez in the passenger seat, when they pulled up next to the BMW and Hernandez opened fire on the two men killing them.

Abreu, the driver of the car, died of a gunshot wound to the chest, while his front-seat passenger, Furtado, died from a bullet to the head. Hernandez pleaded not guilty to both charges, with his lawyers arguing that it was Bradley – and not Hernandez – who pulled the trigger.

While investigating Lloyd’s death in the summer of 2013, police seized an SUV fitting the description of the silver/grey vehicle used in the Boston shooting in July 2012. It was rented in the name of Aaron Hernandez and parked in the Bristol, Connecticut garage of his cousin Tanya Cummings-Singleton. Police also found ammunition in the SUV for a .38-caliber pistol.

Cummings-Singleton, a 37-year-old widowed mother of two who was battling breast cancer, pleaded not guilty in Suffolk Superior Court in Boston on June 2, 2014 to contempt of court charges for refusing to answer questions by the grand jury about her cousin’s alleged role in the shooting of Abreu and Furtado.

The Massachusetts State Police report from the car accident on I-91 in Springfield on June 21, 2013, listed John Alcorn , another Bristol resident who is related to Cummings-Singleton’s late husband, as the possible owner of the .38-caliber pistol seized at the time and later matched through NIBIN with the double homicide in Boston a year earlier.

At the time of the Odin Lloyd shooting, police sources told the Boston Globe that the connection between the shooting of Lloyd in June 2013 and the two men shot to death in Boston the year earlier could have been that Lloyd knew too much about the Boston killings, including the identity of the triggerman.

In April 2015, a jury found Hernandez guilty of shooting Lloyd in a field a mile from his North Attleboro, Massachusetts mansion. He was sentenced to life in prison for the Lloyd murder. But on April 14, 2017, another jury found Hernandez not guilty in the shooting deaths of Daniel de Abreu and Safiro Furtado, concluding there was doubt as to who had pulled the trigger. Despite that acquittal, five days later – on April 19, 2017 – Hernandez was found dead in his prison cell of an apparent suicide. Due to the fact that his appeals in the Lloyd murder conviction had not been exhausted before he died, that conviction was immediately voided under an arcane English common law principle –known in Latin as abatement ab initio – followed in Massachusetts and some of the other 13 original U.S. states. Dating back over 200 years and translated to mean "from the beginning", the effect of this legal principle is to render the defendant (Hernandez in this case) who dies before all his legal appeals are heard as if he had never been charged and convicted of the crime in question.

Police share dataAs illustrated by how the test-firing of the .38-caliber automatic pistol seized in Springfield in June 2013 was tied to the 2012 double homicide in Boston, the strength of the Forensic Technology system relies on police forces around the world routinely test-firing guns seized during arrests and then feeding the results into national databases, which can be shared across state, provincial and national borders.

In Canada, the system, with tens of thousands of bullets and cartridge cases in its database, is known as the Canadian Integrated Ballistics Identification Network (CIBIN). It has been connected electronically to the NIBIN system in the U.S. since an agreement signed between the two countries on November 16, 2006. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) also pays Forensic Technology for maintenance and to train police technicians on how to use the technology.

Set up in about 2005, CIBIN has produced since that period approximately 3,500 matches, known as “hits”, bringing together crime scene bullets or cartridge cases with the guns that fired them. By comparison, the ATF had 50,000 hits by 2013 since implementing the U.S. system in the mid-90s. Each hit normally links at least two crimes and sometimes more.

The RCMP has purchased and installed Forensic Technology equipment and software in cities across Canada including Halifax, Montreal, Ottawa, Toronto, Regina and Vancouver.

The police department in Calgary bought its own Forensic Technology system in 2011, officially opening it in October 2013 and linking it to the CIBIN database. At the opening ceremony, Alberta Justice Minister Jonathan Denis described the advances in ballistics and forensics technology as “absolutely incredible.” Calgary Police Chief Rick Hanson said the CIBIN system has “allowed us to link firearms and ballistics to criminals and various crimes.”

Calgary has used the technology with great success, but one unidentified ballistician told reporters at the opening ceremony in Calgary that it’s “a tough job,” adding “its not as glamorous as the CSI fellas make it out on TV.”

Although most of the Canadian equipment made by Forensic Technology is owned by the RCMP, any police force in a province where an RCMP lab has been set up can send material to be analyzed there. In Quebec, the RCMP has an agreement with the Sûreté du Québec to run the Montreal lab. The Toronto lab is in the Centre for Forensic Sciences run by the Toronto Police Department.

In Vancouver, Ottawa, Regina and Halifax, the Forensic Technology equipment is set up in RCMP labs. If there is no lab in a province, police from that jurisdiction have no choice but to send their cartridge cases and bullets to an RCMP lab in the closest province.

However, the CBC reported in winter 2012 that the RCMP planned to shut down its labs in Regina and Halifax in 2014 for budgetary reasons, which would present a big blow to crime-fighting and would create a gap in the CIBIN chain in the Maritimes and Saskatchewan. There is a question of where the equipment from those two cities will end up. The bigger question for citizens worried about law and order might be why there are such cutbacks in Canadian forensics capabilities at a time when the federal government subsidizes such crime analysis systems for Third World countries.

Ironically, the RCMP was one of the last national police forces in the world to buy the Canadian-based Forensic Technology system in 2005, and to this day Canadian revenues represent only 1 percent or $500,0000 of the company’s worldwide annual revenues.

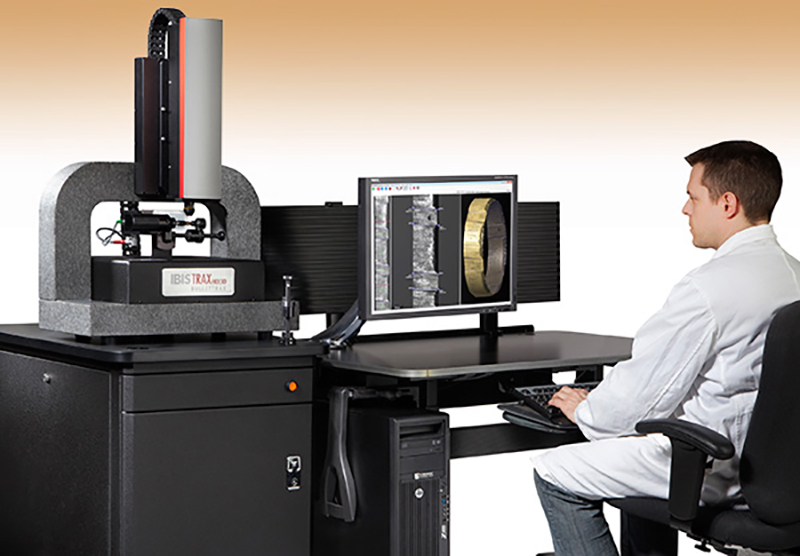

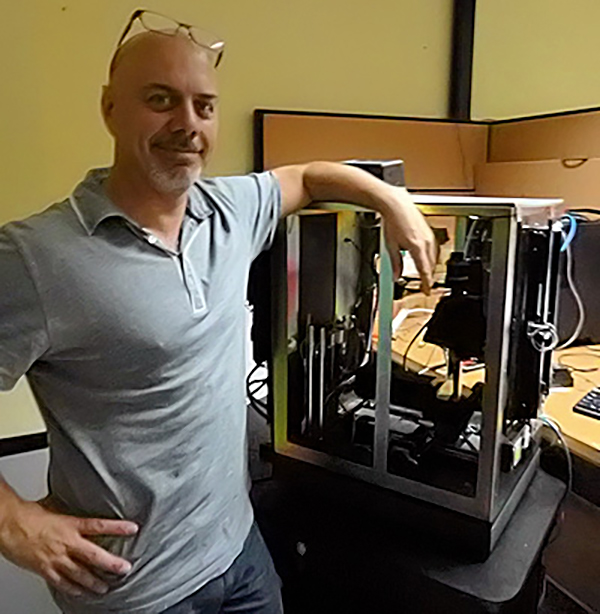

To stay on the cutting edge, Forensic Technology employs five PhDs in R & D at its Cote St. Luc office, which has resulted in major upgrades of the system three times in the last 20 years. For example, until five years ago, all American installations were the original Heritage system introduced by the company when it started out in the mid-1990s. By 2013, all but about 40 of the American labs had switched to TRAX-3D a three-dimensional scanning system introduced in 2007. In 2013, the company introduced its latest high definition upgrade called IBIS® TRAX-HD3D.

Individual installations can run from $250,000 for an analysis unit for cartridge cases only to $1 million for a setup to analyze both cartridge cases and bullets with two large servers, one to collect data and one to co-relate it using an algorithm tied to test-firings. Of course, big clients such as the ATF can negotiate discounts based on bulk purchases.

In 2008, the ATF and U.S. Justice Department signed a five-year contract in excess of $60 million (U.S.) for Forensic Technology to provide technical support for over 130 NIBIN labs in the U.S., with options for modernization upgrades, its fifth contract with Forensic Technology since implementing the IBIS system in 1993. In October 2013, they signed a new five-year contract worth $73.4 million.

Mexico will soon be No. 2 on the list of clients with 40 Forensic Technology systems to be installed in 2014, replacing South Africa which had been No. 2 on the list recently with 28 such systems. But the U.S., with tens of thousands of annual shooting deaths, will likely always be the No. 1 client for Forensic Technology. In one city alone — Chicago — there were 214 shooting deaths between January 1 and August 14, 2013, most of them gang related.

ATF was a believerOne of the first ATF agents to become a believer in Forensic Technology’s system was Pete Gagliardi, who met company president Robert Walsh in January 1993 in Washington D.C. at a 1 ½-hour luncheon meeting organized at the Canadian embassy to showcase the company’s bullet identification system.

For Walsh, a mechanical engineer by training who had graduated from McGill University in 1965, this was a new business. Since 1969, he had owned and operated a company of architects and engineers called Walsh Process Control, which in 1987 became Walsh Automation and specialized in setting up automation services for manufacturing plants throughout North and South America, as well as Asia. His expertise was creating computerized systems to control temperature, air flow and pressure in manufacturing facilities. What did he know about guns and bullets? Not much at that time, but he did recognize a business opportunity when an ex-RCMP agent who had become a firearms examiner approached him in 1990 to ask whether he could set up a system to automate ballistics analysis. The ex-officer explained that police labs could not keep up with the workload created by more gun crimes attributed to an explosion in drug use in the 70s and 80s.

So Walsh called his cousin Bill, an FBI agent, who organized a meeting in Washington in December 1990 with senior FBI officials who confirmed that police could not keep pace trying to match bullets, cartridge cases and guns used in crimes. Evidence sometimes remained locked away in cabinets and drawers for years without ever being tested.

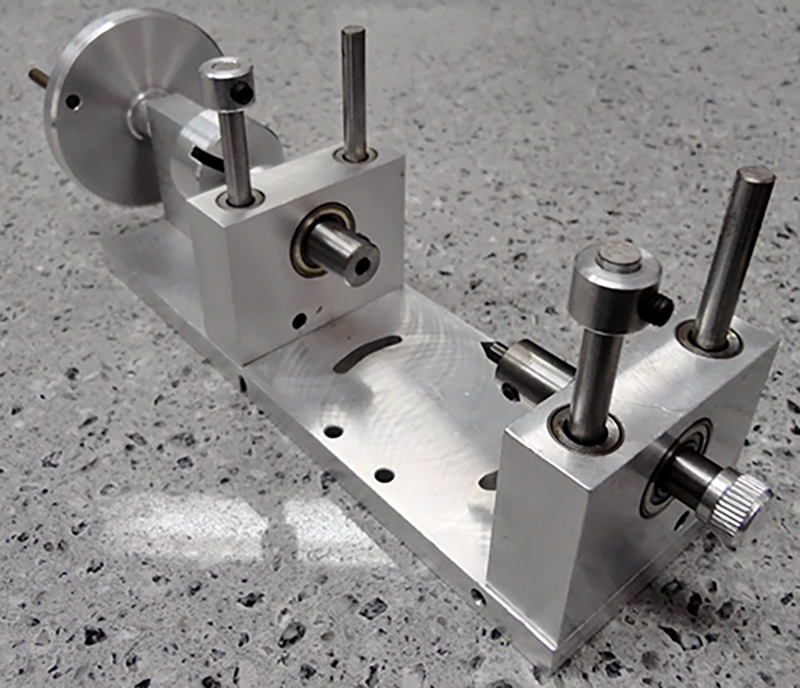

So in early 1991, Walsh consecrated some company resources to R & D, coming up with a prototype of a rotating device to hold and scan bullets, with the bullet markings fed into a database and an operator able to view the details on a monitor. It created quite a stir that year at a Texas meeting of the Association of Firearms and Toolmark Examiners, also known as ballisticians.

Walsh was smitten with this novel, “fascinating” switch in business direction. So he incorporated a new company called Forensic Technology in 1992 to develop and market the business full-time.

When he found himself at the Canadian embassy in Washington, D.C. on that January day in 1993 sharing a chicken luncheon with 15 law enforcement officers from the ATF, FBI, U.S. Justice Department and RCMP, he had confidence that he could elicit interest with a video of his new product.

It didn’t take long. About 90 minutes after the presentation, the ATF called the embassy and asked for a Bulletproof model machine which they could try out. Within six months, they had bought it. They also bought a machine for the Washington Police Department and in short order were getting “hits” or matches from exhibits stored by the ATF and the Washington police.

What makes this Canadian success story even more amazing was that the FBI was developing its own computerized analysis system at that time in 1993 — known as Drugfire — for cartridge cases.

The ATF, using Forensic Technology’s Bulletproof model for analyzing bullets, called its system Ceasefire. The ATF’s system was financed by the Treasury Department, while the FBI’s system was supported financially by the Justice Department. The two systems competed for a few years for funding, as well as for the attention of state and local law enforcement officials.

Walsh recognized that he had a tiger by the tail and decided to jump in with both feet, selling to police forces across the U.S., Asia and Europe while at the same time starting work on a system to analyze cartridge cases, which were usually less damaged than bullets fired from high-powered assault weapons such as AR-15s, AK-47s and Uzis. The cartridge system called Brasscatcher and the bullet system called Bulletproof were combined into the 2D system called IBIS (Integrated Ballistics Identification System) in 1995.

By 1997, the ATF and the FBI decided to unify their Ceasefire and Drugfire systems into the program known as NIBIN (National Integrated Ballistics Information Network). The three-member NIBIN Executive Board was composed of the FBI, ATF and the Boston Police Department, representing state and local law enforcement.

The intent was to make the Drugfire and Ceasefire systems interoperable, but after extensive research by the National Institute of Standards and Technology, it was determined that the two systems were not compatible. The NIBIN board of directors selected the ATF’s Ceasefire system — based on Forensic Technology’s IBIS system — as the preferred choice to become the sole national operating model for ballistics imaging among U.S. law enforcement.

In 1999, some of the features of the FBI system were incorporated into Forensic Technology’s new Remote Data Acquisition Station, which replaced the original IBIS and Drugfire systems, becoming known as the 2D Heritage IBIS. It was agreed that the new Heritage system would use the secure, high-speed telecommunications network of the FBI and the Department of Justice.

By 2005, the 2D Heritage IBIS system had evolved into 3D and by fall 2013 a new HD3D system was available.

By 2000, Walsh had sold Walsh Automation to concentrate full-time on Forensic Technology. One of the people he never forgot was ATF field agent Pete Gagliardi, who had been one of the first and most fervent proponents of the Forensic Technlogy system during the Washington luncheon at the Canadian embassy in January 1993.

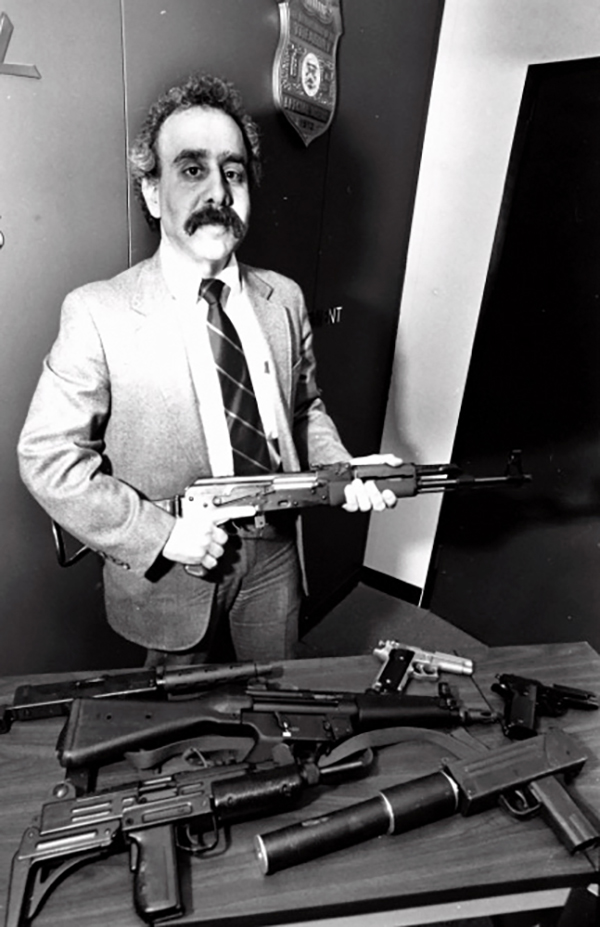

Short, smart and sassyAfter retiring in October 1999 after 24 years as a senior investigator with the ATF, Gagliardi was hired by Forensic Technology to travel the world giving symposiums to police and prosecutors on how to integrate the IBIS technology into their investigations.

Like trainer Jasso, Gagliardi’s passion for his career at Forensic Technology jumps out at an interviewer who is charmed by his rhythmic Boston cadence as he relates episodes from his life-long pursuit of criminals.

It wasn’t always easy being a 5 foot, 4 inch cop (he exaggerates to most people, telling them he is 5 foot 5) on the beat of the tough streets of Boston and New Haven, Connecticut where he started his career in 1969 as a crime scene technician with the police. “Fighting wasn’t my go-to thing,” he recalls.

He was too short to be accepted as a police officer with the New Haven Police Department, but when the federal government opened up an inner city housing project there shortly after, there were no height restrictions for its police officers, so he was hired.

In 1976, he joined the ATF where the brass immediately recognized his potential as a plain-clothed undercover investigator for the simple reason that he didn’t look like a cop. He quickly learned that a sharp brain and a quick tongue are worth at least 12 inches in height as a combat advantage.

There he was one evening in 1978 en route to meeting an informant in a Quincy, Massachusetts (a Boston suburb) restaurant when he saw his man in a nearby parking lot talking to three or four characters he didn’t recognize, including an hombre holding a sawed-off rifle with a silencer.

Suddenly he hears a voice shouting: “That’s the guy who ripped us off. Shoot him!” His hand instinctively feels for the .38 caliber, Charter Arms, five-shot revolver tucked in his pocket.

Rule No. 1: Don’t panic. He keeps walking towards the menacing man holding the rifle who is making the noise. Now Gagliardi lets his tongue take over, asking why the man is upset. Seems that Gagliardi thought that he had bought a shotgun from him a couple of weeks earlier, but the man considered it a rental, not a sale.

No problem, says Gagliardi. He’ll return the other gun. Meanwhile, would El Loco (“The Crazy One” in Spanish) be interested in selling the sawed-off rifle with the silencer? Turns out the dude had a love affair with his sawed-off firearm and insisted on demonstrating at a nearby park how well it worked. Gagliardi returned to the park later the same night and discreetly picked up the expended .22-caliber cartridge cases, taking them to local police who issued an arrest warrant for the Fearsome One on charges of possessing a restricted weapon. The guy ended up in jail, ensuring that the cover of Gagliardi’s informant remained protected.

“I made sure my height was to my advantage,” Gagliardi recalls of his days in undercover work. “I made sure to be completely disarming. I was confident I could always talk my way out. That was my golden ticket. I’m sure that’s why the ATF hired me. They found out I had a brain.”

The same brain that Walsh later hired to give symposiums to police technicians worldwide based on a book he has written called The 13 Critical Tasks involved in solving gun crimes.

Gagliardi, who has four grown children and lives with his wife on Cape Cod, has not strayed far from his crime-fighting roots in this his second career at Forensic Technology. He calls his five PhD colleagues a “warehouse of knowledge” about crime-fighting “which they don’t teach in schools.”

This crime-fighting technology has spread far and wide. On a recent visit to the company’s offices in the Montreal municipality of Cote St. Luc, I saw components awaiting shipment in boxes addressed to Jordan. The company, which is incorporated in Canada, the U.S., Brazil and Ireland, offers 24/7 global support to its clients through an office in Largo, Florida (near Tampa).

Forensic Technology employs software developers, electro-mechanical engineers and researchers to keep the company on the cutting edge, emphasizing R & D to deal with new ammunition and firearms coming on the market.

Like most consumer markets, ballistics have not been immune from disruptive technology. For example, who would have believed a few years ago that 3D printers costing between $1,500 and $5,000 could create a plastic gun capable of firing real bullets? In May 2013, the U.S. government ordered a Texas-based company to remove from its website blueprints for a plastic handgun which it said it had made on a 3D printer and had successfully fired.

On October 25, 2013 British police announced they had seized from gang members components of a gun made from plastic on a 3D printer and were testing to determine whether it was a viable weapon. In Canada, the federal government announced on October 21, 2013 that it has asked the RCMP, the Canada Border Services Agency and Criminal Intelligence Service Canada — which coordinates criminal intelligence among police forces across the country — to study the issue of 3D technology as it relates to guns and to determine whether software controls could be imposed on such printers to prevent guns being made. Paul Murphy, a South African-born, Forensic Technology firearms examiner with 28 years experience in the field, said in a telephone interview in November 2013 that he was present when a 3D printed gun was test fired; it blew up during the firing of the first shot because the barrel was not made of sufficiently hard material to withstand the pressure of a bullet passing through it. He was aware of other 3D printed plastic guns that blew up during test-firings, but he said he was also aware of 3D printed guns that were successfully test-fired.

Murphy said he has heard claims that a plastic gun could work if a metal sleeve was inserted into the barrel, but that he had not yet had a chance to test such a customized firearm.

If a gun made of sufficiently hard plastic could be made to work, it would prove challenging to find identification marks on a bullet passing through its barrel, he said, because the copper or other metal that bullets and bullet jackets are made of is generally harder than the material of the 3D printed guns. He went on to say that if the barrel diameter of a printed plastic gun was bigger than the bullet (projectile), it would be that much harder to find any suitable marks on a fired bullet because the bullet would not come in contact with the whole barrel — only parts of it, comparing such a situation to a bowling ball rolling down a bowling lane.

In November 2013, California-based Solid Concepts, which produces 3D commercial prototype systems, raised eyebrows for being the first to use a 3D industrial printer to manufacture a handgun made of stainless steel and Inconel 625, a corrosion-resistant alloy that can withstand the high pressure and kinetic energy exerted by a bullet exploding out of a gun barrel.

The 3D steel gun is based on the M1911 semi-automatic pistol with .45 ACP [Automatic Colt Pistol] cartridges, which was the standard-issue sidearm for the U.S. armed forces between 1911 and 1985. The 3D steel gun barrel successfully withstood chamber pressure above 20,000 pounds per square inch during every one of its 50 test-fires, the company said.

Murphy told BestStory.ca that such a 3D steel gun “should work like any regular factory-manufactured firearm.” It would also leave easily identifiable marks on fired bullets for ballistics experts seeking to follow a crime-scene trail.

But for anyone thinking of purchasing an industrial 3D printer capable of producing such a steel gun, Solid Concepts noted that it would cost more than a college education, putting it well into the six-figure range.

So while 3D steel guns are out of most people’s price range and plastic 3D models have yet to be proven reliable, there is a plethora of traditional handguns readily available to the public at a low cost. This means that 3D handguns are likely to be relegated as a novelty item in the immediate future rather than as a weapon of choice. But it’s still a development that has to be monitored by ballistics analysis experts, such as those at Forensic Technology.

It’s such challenges which keep company founder Robert Walsh motivated and as enthusiastic about his career at age 70 as he was when he first laid the foundations for his company more than two decades ago.

It’s an industry which is part high technology, as exemplified by the company’s multi-million-dollar annual R & D research budget, and part old-fashioned gumshoe perseverance and street smarts as personified by former undercover ATF agent Pete Gagliardi. who still works on behalf of Foresnsic Technology with police forces around the world on best crime-fighting practices.

“Not a day goes by that we don’t hear of a success story about our crime technology helping to put a murderer behind bars for life,” Walsh told me. “It’s very rewarding.”