Updated: NOVEMBER 2012

Published: JULY 2012

Canada’s toughest cop tells all

Little Albert’s whacky world of bullets, beatings and bad guys

By WARREN PERLEY

Writing from Montreal

Editor's Note: Albert Lisacek died of colon cancer on November 20, 2012, 4 1/2 months after we posted this profile on him. An account of his last days in the hospital can be found in Notes From The Editor in the public section of our website.

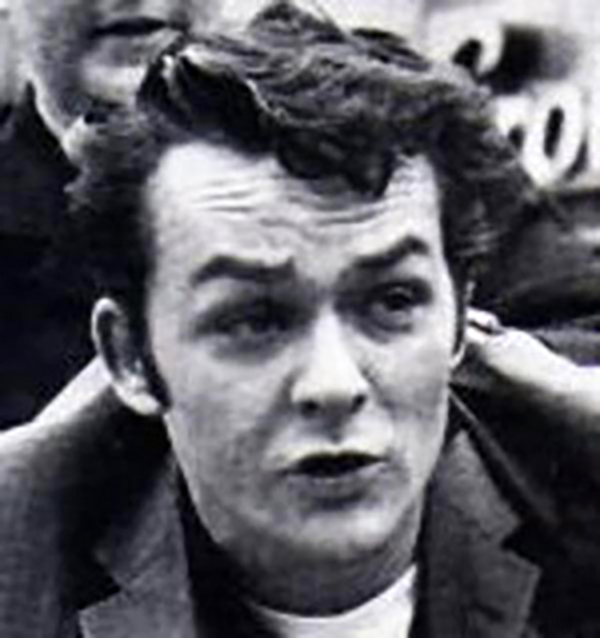

It’s no fun losing your testicles in a shootout with Canada’s toughest cop. But then again, Det.-Sgt. Albert Lisacek was never known as a guy with a sense of humour during his 25 years on the job with the Sûreté du Québec (SQ).

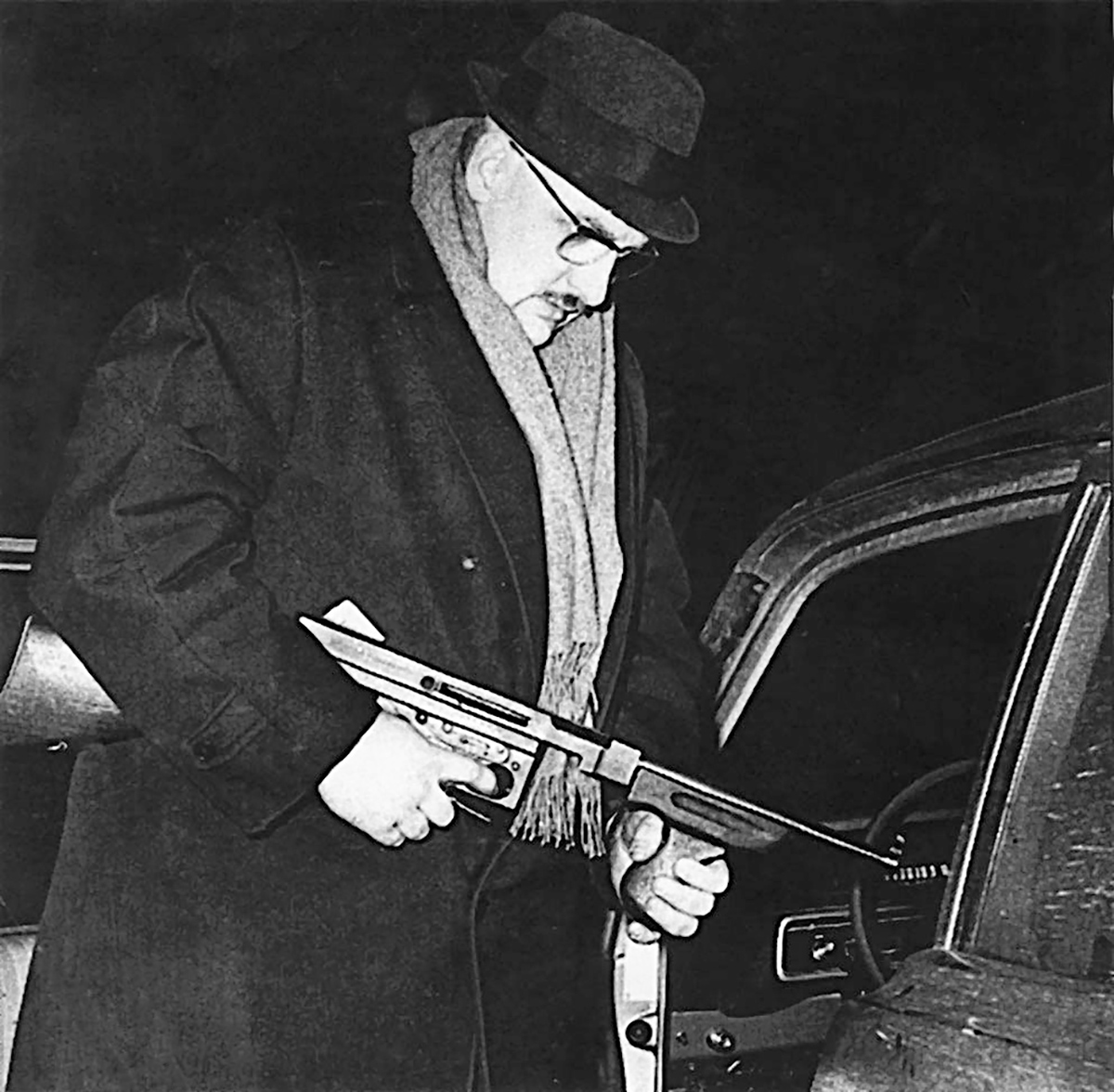

It took me 40 years to find out what happened to the robber who went from a baritone to a falsetto with one squeeze of Lisacek’s beefy finger on the trigger of his 1926-model Thompson submachine-gun. It’s the same type used by Eliot Ness and his Bureau of Prohibition agents, known as The Untouchables, in their 1929-1931 battle against the Chicago mob of Al Capone.

It was November 1972, and I had been on the job six months as a rewrite man in the Montreal bureau of The Canadian Press when one of our reporters scanning police communications picked up word of a shootout between the SQ — Quebec’s provincial police force — and three robbers. “One suspect down; Lisacek is pursuing the other two,” our police reporter yelled into the newsroom.

My editor told me to call Lisacek’s then-wife, Claudia, at their house, seeking reaction from her to the shootout. Nothing in my English literature studies at McGill University or my writing the occasional sports article for the McGill Daily had prepared me for this boffo slice of newsroom life. What could, or would, a wife possibly say when informed that her husband was involved in a shootout?

“Just, do it,” my editor ordered. “Here’s their private number. She’s always good for a quote when Lisacek is shooting.” With trembling fingers, I dialed the number. A gruff female voice at the other end of the line, answered: “Oui?” I began stammering in my broken French that Det.-Sgt. Lisacek was involved in a gun battle. Before I could spit out my sentence, she cut me off in English with a heavy Quebecois accent, “How many has he shot?”

“One of three robbers,” I replied.

“Tell the bastard he better shoot all three or there won’t be any supper on the table tonight,” she yelled. Click. She hung up. I had my quote and my first peek into Little Albert’s whacky, heart-pumping world of crime and punishment. “Little”, as in 6 foot, 2 inches and 250 pounds of muscle, with knuckles the size of loonies and a shaved head à la Kojak’s Telly Savalas. But unlike the Kojak of of the 1973-1978 television crime series, Albert was never known to hand out lollipops. If you were a hood, you didn’t want anything he had to give because it was going to be a bullet or a beating.

Several years later, I was introduced to Albert by a mutual acquaintance, one of the few people he considered to be a friend. So, when he took his early retirement at the age of 48 in 1981, I was the journalist sent by The Gazette, my employer at that time, to write a brief farewell article.

Now almost 40 years after my first exposure as a journalist to one of his shootouts, I decided it was time to use the new model of online, long-form journalism at BestStory.ca to tell the real story of a police officer from a bygone era. One who was motivated to do what was right, not what was expedient, who put his life on the line to protect ordinary, law-abiding citizens. A cop who wouldn’t last a single day on the job in the 21st century world of police bureaucracy and political correctness.

Stakeout erupts into shootoutDuring the course of our first six-hour interview and several follow-up sessions, I asked Albert about that November 1972 shootout which led to my calling his wife at the time. It seems that the SQ had received a tip about a robbery that was supposed to go down in a store in the Montreal municipality of Verdun where there was a lot of cash on hand because it doubled as a license bureau. Two unmarked police cars, one with Albert and his partner and a second one with two other officers, parked nearby.

Albert’s car was one block away in front of a garage, where a bus pulled out, blocking their view. By the time they maneuvered their car around the bus, the robbery was in progress. The officers piled out, shouting “Police” and three robbers took off on foot, running towards a nearby getaway car.

One of Albert’s colleagues emptied his M-2 sub-machinegun clip, with the bullets decimating a nearby mailbox. Meanwhile, Albert was in hot pursuit of one of the three suspects who had in his hand a black object that Albert — in the limited light of a dismal, cloudy November afternoon — took to be a gun. It turned out later not to be a gun. A burst of three bullets from Albert’s Thompson brought the suspect down in a writhing heap.

The two other suspects kept running with Albert close behind; so close, in fact, that he could see the discharge flame from their guns as they fired on him. One suspect slipped on the gravel as he tried to enter the car and slithered behind a pole where Albert cuffed him. When asked who had the stolen money, the robber cussed the police. Albert’s reply: a kick in the kisser.

The third suspect managed to jump into the car and started driving when Albert let loose with a spray of bullets from his Thompson, shattering the back window. The bullets ripped through the back and front seats before hitting the leather jacket of the suspect as he lay supine on the front. The car hit a pole, bringing down three clotheslines. Albert figured the suspect in the car was dead, but it turned out that the bullet had lost its force by the time it hit him, failing to penetrate his body.

“Non, je suis pas morte” [“No, I’m not dead.”], the suspect blurted out. Albert picked him up by the hair and spread eagled him on the hood of the car, demanding, “Where’s the money? Where’s the money?”

“Mange la merde “[“Eat shit.”], the suspect retorted. That lack of civility angered Albert, so he kicked him in the face, which led to the revelation that the first suspect who had been hit by three bullets was the one with the money.

Albert walked back to where the first suspect lay groaning on the ground, “Tue moi, tue moi; c’a fait mal.” [“Kill me, kill me; it hurts.”] Turns out the three bullets had hit him in the genitals. He was taken to hospital, but they couldn’t save his testicles.

“I felt sorry for the guy,” Albert says now as he recounts the event of four decades ago. “But what could I do? He had a black object in his hand that looked like a gun. So I let him have it.”

A few weeks later, as he sat in the courthouse hallway waiting to testify at the trial of the three suspects, Albert observed an old man pacing the corridor, muttering execrations which all ended with the name, Lisacek. He was surprised at what he was about to hear. After a few minutes of restraint, Albert identified himself to the gentleman, asking what he had against Lisacek.

The man said he was the father of the suspect who had been captured in the front seat of the getaway car. “You should have killed the son of a bitch,” he said, referring to his son. “Then I wouldn’t have had any more trouble with him.”

‘He shot my balls off’All three suspects were convicted of armed robbery and went to prison. Years later, after he had served his time, the robber who was shot in the groin met Albert’s nephew at a party in Ontario and told him, “I’d like to kill your fucking uncle. He shot my balls off.”

He was just one among many hoods who would have given their eye teeth to knock off the most flamboyant and publicly recognized cop in Quebec. There were likely even some fellow officers who would have wished to see him disappear during his 25-year career with the SQ. He was just too blunt and tough. Albert enforced the law his way and didn’t play nice with bureaucrats. He was Dirty Harry before that fictional renegade detective was even born in the 1971 celluloid persona of actor Clint Eastwood.

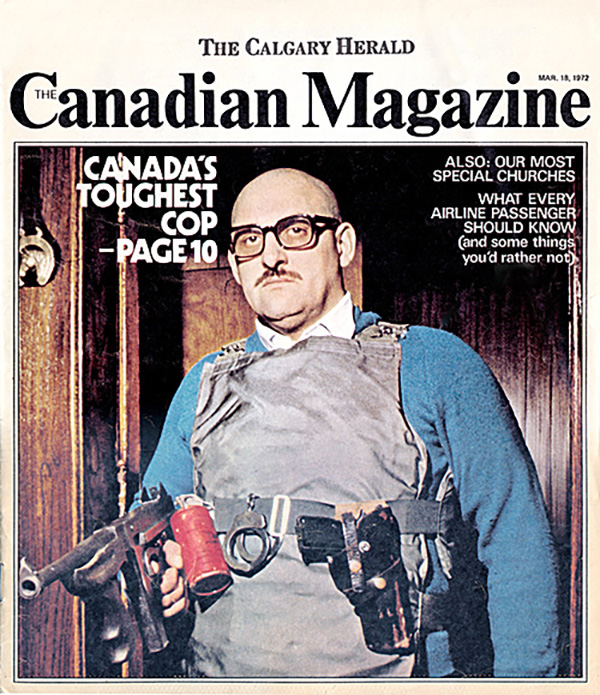

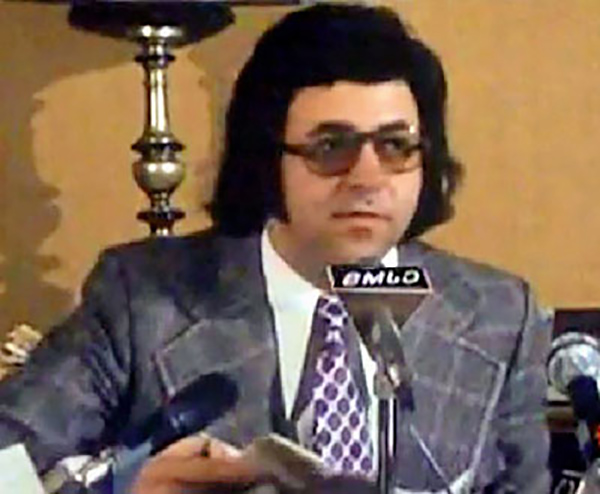

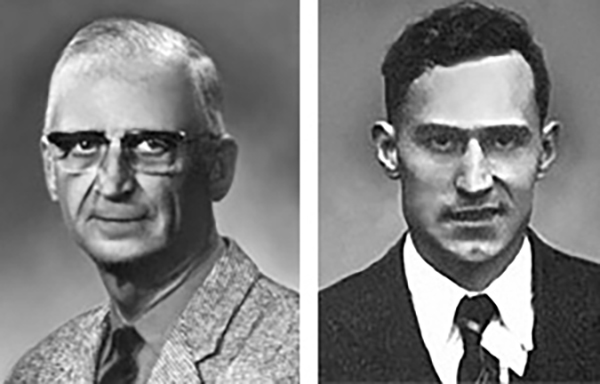

By March 18, 1972, Albert had already been anointed “Canada’s Toughest Cop” in a cover story in The Canadian Magazine, the Southam newspaper chain’s glossy, weekend insert in newspapers across the country.

Journalist Tom Alderman’s story carried the headline, “Would You Invite This Man To Your Tupperware Party?” The subhead chimed in, “Doesn’t Matter. He’ll come anyway.” The story noted that Lisacek was usually the first officer in on holdup raids, breaking the door down with a powerful kick of his right boot. Turns out that shortly before the article ran, Albert got a bum tip, breaking into a Montreal apartment, waving his sub-machinegun in front of ladies holding a Tupperware party. In Albert’s words, there were “broads fainting left and right; I really felt bad about that.”

In his article, Alderman described the job criteria for the first cop through the door in a holdup raid: “Someone mad, foolish or courageous.” Why? Because “men who rob banks for a living are notoriously violent and unpredictable,” Alderman wrote.

And none was more unpredictable and violent in the ’60s and ’70s than Richard Blass, nicknamed “The Cat” for his three escapes from prison and four unsuccessful attempts on his life by the Mafia, including two bullets to his head and two in his back in an ambush in a Montreal garage in October, 1968. Declaring war on the Vincent Cotroni clan, Blass tried but failed in May 1968 to kill Vincent’s brother, Frank, although he managed to fatally shoot two other Mafiosi in the same ambush. His beef? Blass didn’t want to split his ill-gotten gains with the Italian mob. He was suspected of 20 homicides, but was never convicted of murder because of a lack of evidence.

Lisacek says now that the investigation of Blass was the responsibility of the City of Montreal police in the 1960s and ’70s. “If I had been investigating him, he would have been dead a lot earlier,” he adds. As it was, their paths crossed after Blass got caught in a bank robbery in Sherbooke, Quebec in 1969 during which a police officer was wounded.

Cop meets ‘Cat’He was transferred to Bordeaux Jail near Montreal to await trial. When that day arrived, Quebec’s toughest cop, Lisacek, was assigned to escort the province’s most dangerous bank robber, Blass, for the 120-mile journey from Montreal to Sherbooke. The animosity between the two had already been well established through the Quebec tabloid press which thrives on stories about cops and robbers. Blass, known never to back down, mocked the hulking Lisacek in newspaper reports, calling him a “poodle”. Lisacek held his tongue, but now says he thought of Blass as “a lousy, dangerous criminal who had to be taken out.”

Their fatal date with destiny would occur on January 24, 1975 amid a hail of bullets which left Blass dead in a chalet in Val David, a Laurentian mountains ski resort 50 miles north of Montreal. But the path which led Lisacek to that rendez-vous began decades earlier — on July 13, 1933 when he was born the first of four sons to Joseph and Mary Lisacek, who had immigrated from Czechoslovakia in the mid-1920s.

It was clear right from the beginning that all four boys had one attribute in common — size and strength. None was smaller than 6 foot, 2 inches, and Joe, the second eldest who became a machinist, was 6 foot, 5 inches. Bill, the third son, became a policeman with the City of Montreal, while Milan, the youngest, was a dog trainer, primarily of German Shepherd seeing-eye dogs and Doberman attack dogs.

Their size and strength was at least partially due to genetics. Their father, Joseph, had a part-time job as a strongman in a circus in Bratislava, the capital of Slovakia, before he migrated to Canada in 1927. Anyone who could pin him was offered a reward. Nobody ever collected. Despite the fact that Joseph was relatively short at 5 foot, 10 inches, he was chiseled in granite. Stories abounded about his strength and endurance. Albert’s mother, Mary, was a tall woman at 5 feet, 11 inches.

It was apparent early on that Albert was different from his brothers. He was a loner. When the boys decided to scrap — as happened frequently — it was usually three-on-one against him. He learned at any early age to wade into a fray of big bodies, with legs and arms pumping. And if the battles got too rough or went on too long, you could always count on Mary to intervene, beating her boys’ butts with some vigorous swings of her broom or a wood hockey stick

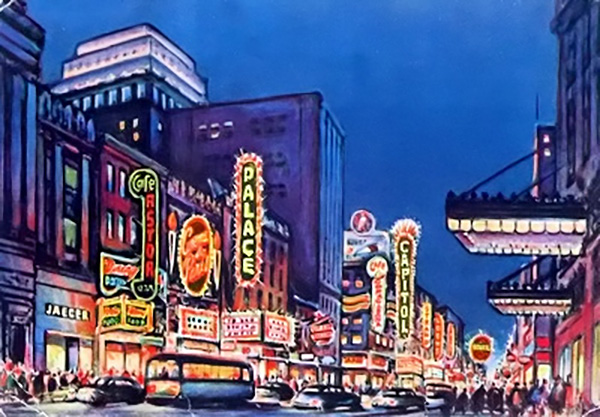

They played cops and robbers in the alley behind their rented, two-bedroom, ground-floor flat located in the immigrant district of St. Dominique Street near Roy Avenue, close to Montreal’s fabled St. Lawrence Boulevard, better known as The Main. Albert, who learned his French on the street, always played the cop, chasing the robbers played by his brothers and other neighborhood kids, some of whom actually went on to become criminals.

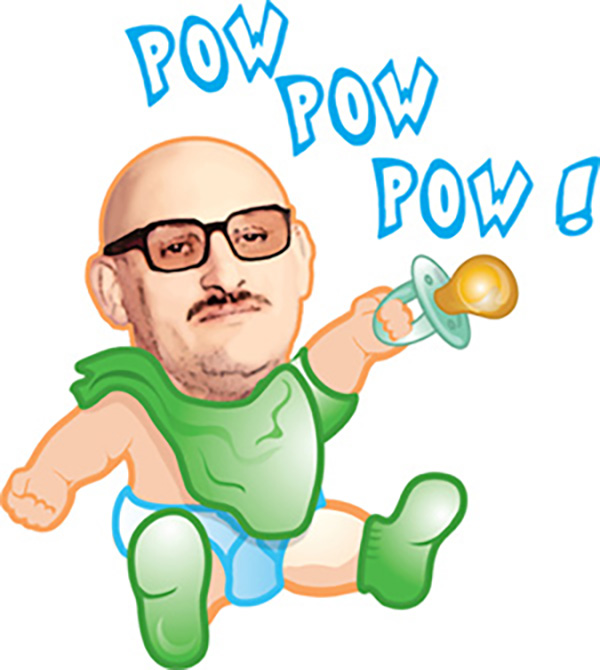

Clutches pacifier like a gunIt seemed as though Albert was destined to be a cop from the time he sucked on his baby bottle. His mother, Mary, told Albert’s first wife, Claudia, that as an infant, he would remove the pacifier from his mouth, hold it in his tiny fingers like a gun and yell, “pow, pow, pow.”

While his brothers played with their clique of friends, Albert loved walking for hours by himself amid the verdant foliage of Mount Royal in the heart of Montreal. He was the quiet one who enjoyed romantic adventure novels about the Old West by American author Zane Grey, a dentist who preferred to write and play amateur baseball than to extract patients’ teeth. A well-written action novel could transport Albert from mundane reality to sublime adventure.

In the English public schools he attended, Albert says he wasn’t “a genius” or “a dummy”. Just an average kid who loved books about the Wild West and geography. He didn’t care for team sports such a baseball or hockey, although he enjoyed kicking the soccer ball around with his dad, who had played the sport in Europe.

His favorite winter pastime was cross-country skiing on Mount Royal on his wooden skis with steel edges. When fall came, the brothers would play football with rags stuffed in a stocking. Theirs was a typical working class family whose father toiled during the Second World War at the Canadian Vickers Ltd. shipyard and in later years as a night watchman at Peerless Clothing.

From an early age, Albert knew the value of hard work and honesty. His mother gave birth to the four babies at home, with Joseph helping with the deliveries. He didn’t have material wealth, but he certainly had his quota of spiritual fulfillment — a loving relationship with his father and mother, and an appreciation of nature’s beauty. He has always loved countryside scenes, especially old farmhouses and barns in the light of dawn.

Growing up, he respected those who followed the straight path of a law-abiding citizen, cognizant of family and community. He didn’t look for trouble, and he didn’t like bullies who preyed on those weaker than themselves. An incident when he was a skinny 15-year-old, before he had grown into his full height and musculature, further motivated him to become a policeman.

Walking on the nature paths of Mount Royal, five rowdy teenagers started chasing him. He ran down nearby Park Avenue and rang the doorbell of the nearest house. An elderly woman of about 80 answered.

Don’t give in to bullies“Lady, can I hide here?” he asked. “They want to beat me up.” Before the astonished octogenarian could make a decision whether to let him in, Albert had scurried past her, slamming the door shut. She made the best of the situation, offering him a soft drink while he waited for the truants to disappear. For his part, Albert resolved that he would never again be bullied or permit other innocent people to be victimized by hooligans. That first lesson — don’t give in to bullies — was to become the first ingredient in the recipe for making the toughest cop in Canada.

Within a few years, Albert had given up typical teenage pursuits, such as dating and Friday night movies, opting instead to spend his money on a membership in a neighborhood basement gym where he practiced boxing and wrestling while hoisting heavy weights, five days a week, three to four hours a session.

By age 20, he had grown to his full height of 6 foot, 2 inches and packed 250 pounds of heavy muscle on thick bone with a 34-inch waist. About that time, during one of his walks on St. Catherine Street, he saw a crowd surrounding four men, about 19 or 20 years of age, who were beating up a young black man, calling him “a dirty fucking nigger.” Albert’s protective instincts kicked in. He stepped in and “whacked out the bullies one by one” and then put the victim into a taxi to safety.

The martial arts instructor at his gym cautioned him never to hit anyone with a closed fist for fear of killing him. Albert took the advice to heart, especially after becoming a police officer at age 23 and realizing that a slap wouldn’t break a criminal’s skin and leave him open to charges of brutality. His power was such that he was known to knock out adversaries with his open hand.

Employment opportunities for muscle and moxie were aplenty in the Montreal of the 40s and 50s, known throughout North America as “Sodom on the St. Lawrence”, with all-night bars, brothels and gambling dens thicker than flies on honey.

By the time he was 20, Albert was showcasing his muscle and macho as a part-time bouncer at the Trinidad Ballroom on St. Catherine Street. The spot appealed to his sentimental side because it had two bands which alternated between playing three modern dances for the younger crowd and three jigs for the older folks, for whom Albert held a special place in his heart.

Asked whether he encountered problems as a bouncer, Albert replied without hesitation: “Problems never lasted long.” His favorite technique was to grab the rowdy by the shoulders, spin him around, crank his neck and heave him down the stairs leading up to the club. Albert considered it a humanitarian gesture that he never cracked any of the belligerents with his closed fist.

Strike first and hit hardSo, we discover the second ingredient in what would become the recipe for the toughest cop in Canada: Don’t hesitate to impose your physical strength and fighting prowess to subdue troublemakers. A first-strike policy might avoid the need to use deadly force later.

At that juncture of his life, he had a full-time job working as an assistant machinist on the turbines at Dominion Engineering Inc. in Lasalle. Outside work, Albert continued to minister to his quiet, sentimental side, taking long, solitary walks with stops along the way for chats with the elderly Slovak men who lived in rooming houses between Pine and Prince Arthur avenues, just north of the downtown area. Manual labourers, they worked to save what they could to bring their families to Canada.

Although only 20, Albert relished his conversations with the older men who knew his father from their homeland. They enthralled Albert with their stories, such as the tale about a three-hour battle between his dad and a young stud who challenged the circus strongman. Despite his best efforts, the young challenger could not pin the elder Lisacek.

“I liked to chew the fat with them,” Albert recalled. “They were lonely and they enjoyed when I visited. Whenever they saw my father, they would ask about me. For my part, I always made time for them. I liked their stories.”

An old soul in a young, martial body, he empathized with older neighbors who were suffering through illnesses. He made a point of visiting them and helping out in any way he could.

When not working as a bouncer or talking to the old gentlemen on his walks, Albert would take in acts at the various nightclubs, shooting the breeze within the fraternity of bouncers. Even at that young age, he had a tough guy reputation, which could often lead to trouble if a bad dude wanted to make his mark by beating up on the fearsome one. A boxer who acted as an enforcer for the mob decided he would be the one to tarnish Albert’s pugilistic record.

After several provocations, Albert obliged and they duked it out one night outside a downtown nightclub at the corner of Papineau and Ontario streets. In his words, Albert was “whacking him out” when six other Mafia enforcers jumped in, at least one with a blackjack, and beat Albert unconscious, knocking out several teeth.

‘Who wants to die first?’It was the first and only fight he lost. It would become another valuable lesson and the third ingredient in the recipe for toughest cop in Canada: “After that I always carried a gun. If anyone pulled one on me, I pulled out my piece and asked, ‘Who wants to die first?’”

In his future police career, that reputation for throwing the first punch and being ready to fire the first bullet would lead to tabloid headlines aplenty, with hoods decrying him as a government-sanctioned killer hired to decimate their ranks.

Albert quit Dominion Engineering and his job as a bouncer at age 22 to become a nightclub manager on The Main, but even a tough guy knows better than to continually get between hookers ready to bite, kick and scratch their way to turf dominance. He quit that job after six months, but not before turning down a job offer from the man in charge of the protection rackets for Vic Cotroni, who was then the Godfather of the Montreal Mafia.

Albert tried his hand briefly as a private eye, but chafed at the entreaties of irate wives beseeching him to catch their husbands in the act of cheating. He hadn’t packed on 250 pounds of muscle to carry around a camera to record examples of a husband’s carnality in flagrante delicto. He left that job after four months.

By the time he was 23, it was obvious that there was no career other than police work which would satisfy the temperament of a rough-and-tumble young man who detested bullies and who had always wanted to be the guardian angel of society’s most vulnerable. Those were the days — 1956 — before police academies and training programs.

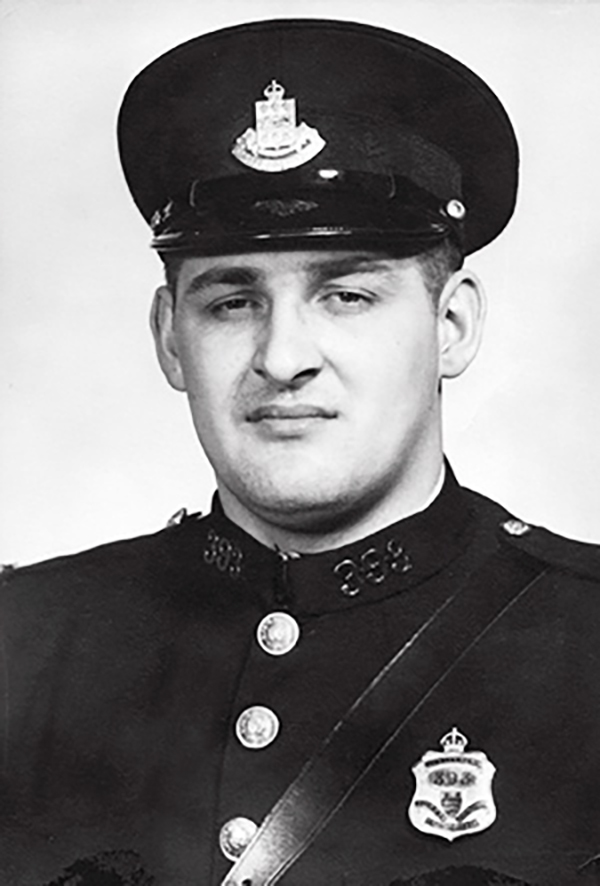

Brass buttons and a gunOne look at him, and the Sûreté du Québec brass knew it had some serious beef on the hoof. He was given a starched dark blue uniform with brass buttons, a Smith and Wesson revolver, badge No. 393 and an assignment working the cells at SQ headquarters, located at that time in the courthouse.

Albert put his first-strike policy to the test there when one of eight prisoners in a holding cell swore at him in French, “Maudit Crisse de Polak.” Although he was of Slovak, not Polish descent, Albert’s sensibilities were offended.

Albert told the guards to open the cell door and to lock it after him. No real-life cop, other than Albert, would willingly incarcerate himself in a cell with eight ruffians. But the rookie wanted to prove a point that the best way to handle bullies is to bully them. None of the eight would admit to uttering the epithet. Here’s how Albert describes what ensued:

“I grabbed the first guy I saw and gave him a good slap in the face. Then I gave the same treatment to the second and third guys when they wouldn’t answer. By the time I got to the fourth one, he pointed out the culprit. He was a big guy, so I gave him a good workout and left him on the floor.”

The incident buzzed through the building like electricity in water. The name Lisacek became synonymous with “a real mean son of a bitch”. If you showed disrespect, you could expect an open-hand slap to the face more powerful than most men’s closed fists. Colleagues called him Little Albert. Cons called him Dirty Albert or Le Chien [The Dog]. Everyone had a name and an opinion.

A couple of prisoners complained about the treatment. Albert’s lieutenant warned him not to hit the prisoners for verbal abuse. Albert’s reply: “We’re the boss; not them!” So the brass transferred him to the information desk to greet citizens as they entered the lobby.

As was his habit growing up, Albert was always polite with those who were law-abiding. Of course, when there were problems in the holding cells, such as the nightclub bouncer who didn’t want to empty his pockets before going in lockup, Little Albert would still be called in. A single slap to the side of the head and the bouncer was out cold. Albert emptied his pockets, signed his name and locked him up.

The brass realized it was a waste to keep such talent chained to a desk. So by 1961 Albert was promoted to detective, put in plain clothes and assigned to serve arrest warrants for outstanding fines and traffic violations, as well as subpoenas on businesses operating without proper permits.

By then, he had figured out that operating by the book wasn’t for him. Instead, he used common sense. If someone with an arrest warrant issued against him for outstanding fines promised to come up with the money within a reasonable time, Albert would give him the benefit of the doubt, even if he had a prior record.

Follow the moral compassSo this became the fourth and final ingredient in the recipe for the toughest cop in Canada: Don’t operate by the book; rely instead on your moral compass.

“I had a feeling for people,” he recalls. “I had a heart. If he seemed like a good guy trying to do right, I wouldn’t arrest him. Instead, I’d give him time to come up with the money to pay his fine. The other guys on the force wouldn’t give breaks like that. If they had an arrest warrant for someone, they enforced it.”

There was the father of four kids who drove for a living and had $300 in outstanding traffic fines. If arrested, he would have lost his driver’s license. Albert gave him three months to come up with the money. He remembers that the man started crying because he was so happy not to be arrested. Three months later, true to his word, he phoned Albert to say he had the $300.

He may have been unorthodox, but Albert was successful, collecting an average of $3,000 a day in fines while visiting up to 24 addresses. “I did a lot of mileage and I collected a lot of warrants.”

Of course, if you conned Albert, he’d hammer you. There was the time he visited one man’s home three times to serve an arrest warrant for unpaid fines and left his card each time, asking the man’s wife to have her husband call him. The fourth time, Albert pushed his way past the wife who said her husband wasn’t home. He espied two toes sticking out of a closet. Albert brought his blackjack down hard on the man’s foot, making him “dance like a rabbit”. The suspect limped into court, wearing one shoe and with one swollen, bare foot.

He meted out the worst punishment to violent offenders, such as the recently released prisoner who beat up his sister when she refused to give him money. Albert got the call and rushed to the woman’s flat on busy Mount Royal Boulevard in the working area of Le Plateau.

When he caught up with the con on the street, the ex-prisoner took a swing at Albert, who punched him in the gut, this time with a closed fist. The man crumpled to the pavement. Albert picked him up by his shirt and crotch, hurling him through a plate glass window. He walked into the store, handed his SQ card to the owner, telling him that his window would be replaced at taxpayer expense.

Face meets brickAfter he dragged the cuffed prisoner across the street to his car, Albert, still seething, slammed the man’s face into a brick wall near a pool joint where some motorcycle gang members were hanging out. Once again, ear-splitting chatter reverberated through the underworld jungle about Dirty Albert’s enforcement methods.

When he appeared before a judge shortly after, the prisoner complained about his treatment, saying he needed painkillers. The judge was unsympathetic and sentenced him to six months in jail for assault.

By July 1963, Albert’s exploits had come to the attention of the SQ’s 22-man holdup squad. What better place to harness balls and bravado than in the pursuit of the most daring bank robbers in North America? By then, he had a new badge number: 1862.

In those days, Montreal had the largest, most dangerous collection of bank robbers in North America. As Tom Alderman wrote in his March 1972 profile of Albert in The Canadian Magazine: “Bank robberies appeal to the swashbuckling style of the French-Canadian criminals. The best and most active bank robbers in North America work out of Montreal. Also the most dangerous.”

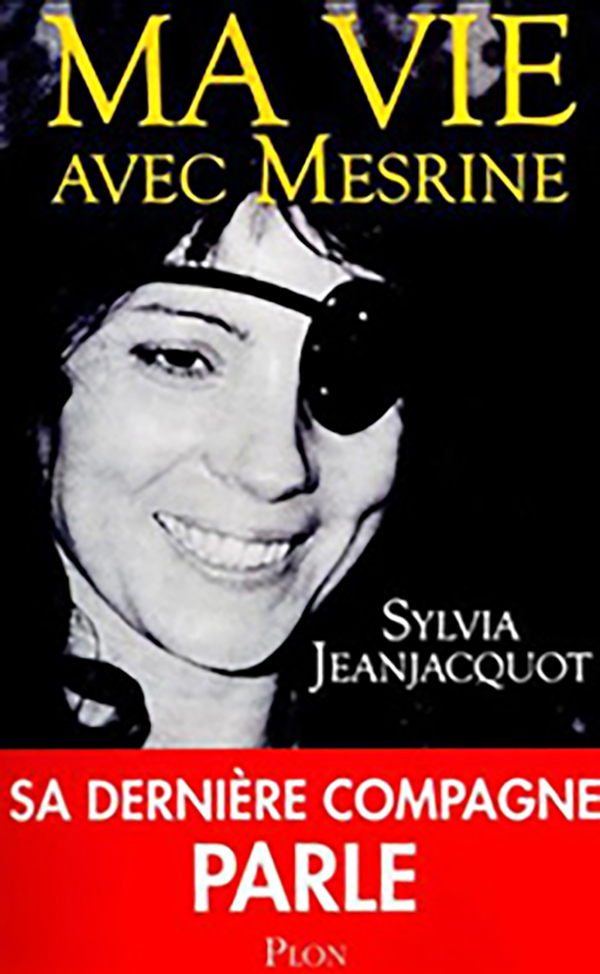

Among them was 5 foot, 3 inch Monica Proietti, better known as Machine Gun Molly, who robbed banks, sometimes with her three young children in the car with her. Jacques Mesrine, a French Army commando in the Algerian War in the ’50s and early ’60s, turned his military skills to robberies in France, where he was on the Most Wanted List before fleeing to Quebec in 1968 to continue his lawless spree. By the end of 1972, he had returned to his life of crime in Europe and was shot to death by police in Paris on November 2, 1979.

There was the East End Gang of French-Canadians, the West End Gang of mainly Irish-Canadian mobsters, and a gang which used a hearse to rob banks. Between 1956 and 1960, there was the Red Hood Gang, whose members wore Montreal Canadiens’ hockey socks over their heads, and there was the bank robber who donned a different hat for each heist.

Between 1961 and ’62, bank robber George Marcotte disguised himself as Santa Clause and robbed several banks in the weeks preceding Christmas. In a shootout with police on December 14, 1962, he fatally shot two officers. He was convicted of first degree murder and sentenced to hang, but had his sentence commuted to life in prison when Canada abolished the death penalty in July 1976.

After his third and final escape from prison in October 1974, Richard Blass became the most dangerous bank robber of them all, going on a killing spree which left 15 people dead in less than three months.

The police high command decided to give the men in blue an advantage by throwing Albert into that mix of madness and mayhem. It was a match made in heaven. He started sharpening his shooting skills with target practice at a summer cottage he bought in 1963 from local businessman Maurice Paquette in Lac des Écorces, a Laurentian mountains resort community 150 miles north of Montreal.

Albert was proficient with a Winchester rifle, a shotgun and his 9mm Browning pistol, with which he had replaced his standard police issue Smith and Wesson .38 Special in 1957. He was the only policeman in Quebec at that time carrying a Browning pistol, the same model used by the Canadian Army. He preferred its easy-to-load cartridge with 13 bullets, compared with six bullets loaded singly for the revolver.

In 1965, he adopted his trademark Thompson sub-machinegun, lovingly referred to as his “Chicago typewriter”, which had been seized by police in a raid. The Thompson is known for being compact, its high volume of automatic fire and the large holes its .45 ACP (Automatic Colt Pistol) cartridges can blast in a target.

U.S. General John T. Thompson started developing plans for the sub-machinegun during the First World War, intending it to be a “one-man, hand-held machinegun” to act as a “trench broom”, together with its .45 ACP cartridge, which the general considered to be a real “man stopper”. The project was initially dubbed “Annihilator I”, but the war ended before it could be brought to market. So in 1919, with the war over, it was renamed the Thompson sub-machinegun after the general who had conceived the idea for such a weapon and who had found the financial backing for its design and manufacture. In the hands of Albert, the Thompson became a “crime stopper”.

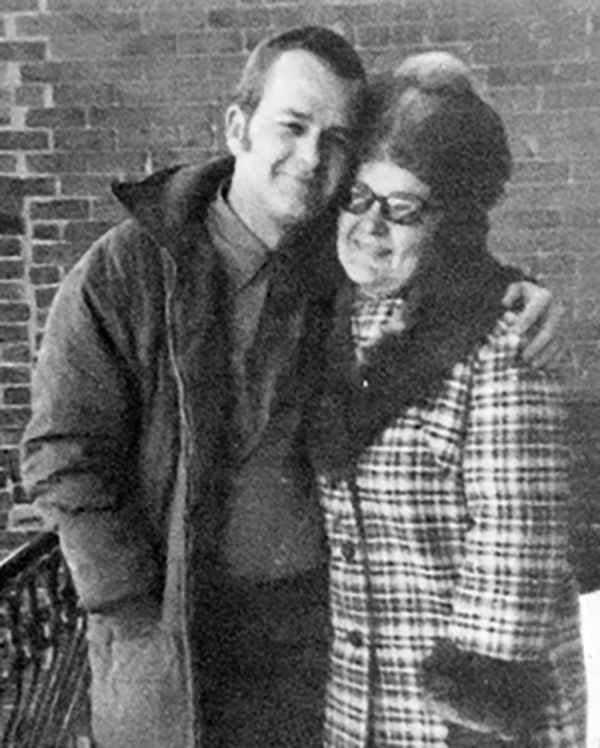

Cruising in a pink CadillacIn the 1960s and ’70s, it was hard to miss Albert when he was in Lac des Écorces for target practice on summer weekends, says Maurice Paquette’s youngest son, Luc. The detective was a larger-than-life presence, cruising in his dorsal-finned, white-roofed pink Cadillac with his little schnauzer, Teppy, on the front seat next to his wife, Claudia, and their 160-pound mastiff, Cheetah, lying on the back seat with Radar, the abandoned, flea-ridden mutt he had rescued from a box on a Hollywood, Florida street where he had been vacationing. He was fond of saying about Cheetah: “If you want to get away from her, you have to leave your arm.”

He’d drop by the service station owned by Luc’s father for a fill-up and an occasional oil change or tune-up. Not for him the Quaker State oil sold at Maurice’s BP station; Albert brought his own supply of synthetic Mobil oil, the brand used at the time by the U.S. Army.

Luc, born in 1964, was an altar boy at Mass where he would see Albert and his wife at services every Saturday night in Lac des Écorces. When in Montreal, the Lisaceks were regulars at the Saturday night services at a downtown Catholic church run by the Franciscan brothers on what was then Dorchester Boulevard, later renamed in honour of former Quebec premier René Levesque.

The road back to the Catholic church was long for Albert, whose mother and father converted to Protestantism just months after he was born and baptized as a Catholic in 1933. It was the middle of the Great Depression and Albert’s mother, Mary, visited the Slovak priest at her Catholic church, seeking help to get her family through the hard times.

As Albert tells the story, the priest refused her request and insulted her. She and his dad then sought help from a Ukrainian Protestant minister at the non-denominational Church of All Nations on Amherst near Ontario streets in downtown Montreal. The pastor gave the family clothes, food and some money. Within a short time, Mary and Joseph had converted to the Protestant sect, and had their three subsequent sons baptized in that church.

Although Albert was technically still a Catholic, he and the rest of his family attended services every Sunday at Church of All Nations, walking the two or three miles each way because they could not afford streetcar fare.

The weekly attendance lasted throughout his childhood and most of his teenage years. There was a lapse of about nine years between the age of 18 and 27, when Albert married Claudia and resumed his weekly attendance, this time in the Catholic church. Just before the marriage ceremony in 1960, the priest suggested to Albert that he take confession. Albert declined, telling him: “If I ever confess to you, you’re going to drop dead.”

Pray the bullets miss youAs befits a man with parents named Joseph and Mary, Albert’s belief in God is profound, although he is open as to how one chooses to worship the Almighty. He says prayers every night. “There’s someone up there who helps you out and protects you,” he told me, confiding he always said a short prayer prior to being the first police officer through the door on a raid. And the prayers all had the same ending: “I hope the hell this isn’t my last time.”

“He was a big, rugged guy,” Luc said in a recent interview, recalling Albert’s presence at Saturday night church services at Lac des Écorces, where he spent summers between 1963 and 2004 when he sold the cottage. “He was very noticeable. He looked like a big bear; very serious, but with a big heart.”

Cross the bear and you could expect a big paw to swipe your face. Like the village blowhard in his mid-40s who visited the Paquette family service station, bragging about how he had watched a black bear eating all day in the village dump and had returned with his rifle and shot the animal dead.

Albert happened to drop by and caught one of the retellings of the story. He cursed the bully out, in what Luc describes as “good French”, for shooting an innocent animal which was doing no harm and then dropped the coward with a whack to the side of the head. “Next time you want to shoot,” Albert told him, “come out with us to hunt crooks in the bush and we’ll see how brave you are.”

Young Luc bore witness that day to a heart that went out to defenceless humans and animals. Albert’s world, like that of the Bible, was one of stark contrast between good and evil. The Old Testament’s Deuteronomy 28:20 quotes Moses as warning the Children of Israel in the wilderness that evil and punishment will ensue for those who forsake the laws and morality of God: “The Lord will send on you curses, confusion and rebuke in everything you put your hand to until you are destroyed and come to sudden ruin because of the evil you have done in forsaking him.”

You needn’t be a student of the Bible to know there has always been, and continues to be, evil in the world. Just read the headlines, past and present, for an appreciation of how wicked people pervert what should be the natural order of life and liberty in order to impose their licentious, demented will on innocent souls.

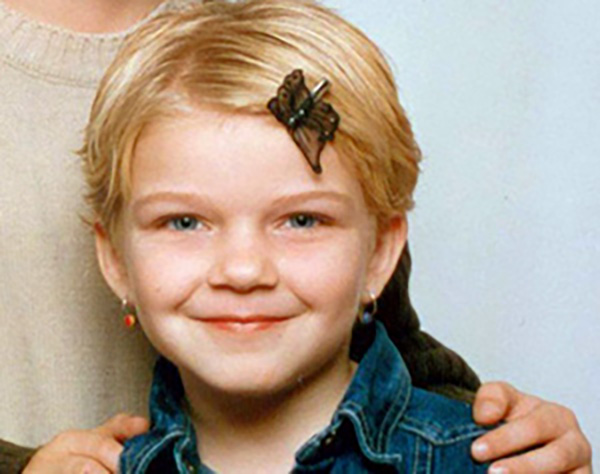

A recent example was the 2009 rape and murder of eight-year-old Woodstock, Ontario schoolgirl Victoria (Tori) Stafford by Michael Rafferty, 31, and his girlfriend Terri-Lynne McClintic. “You, sir, are a monster,” Ontario Superior Court Justice Thomas Heeney said on May 15, 2012 in sentencing Rafferty to life in prison. McClintic was sentenced in 2010 to life imprisonment for the same crime.

“You have snuffed out the life of a beautiful, talented vivacious little girl….,” Justice Heeney said to Rafferty. “And for what? So that you could gratify your twisted and deviant desire to have sex with a child. Only a monster could commit such an act of pure evil.”

A curse on evil-doersAlbert knows well the heart of darkness which beats within violent offenders. Throughout his career, he was the biblical curse on such evil-doers. “I was good at getting rid of the bad people,” Albert recalls. Just as with Dirty Harry, there were bureaucrats who did not like his methods, but that didn’t stop them from calling when they needed someone to smash down the door in a raid and to be the first one in.

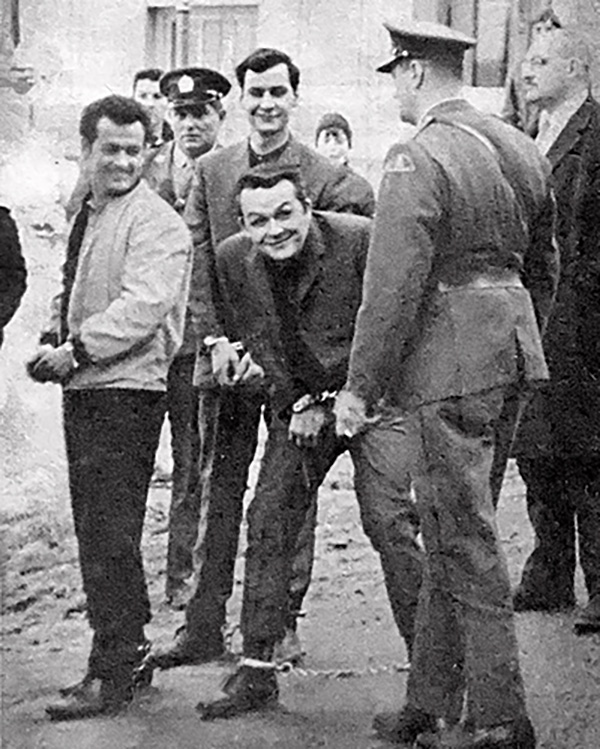

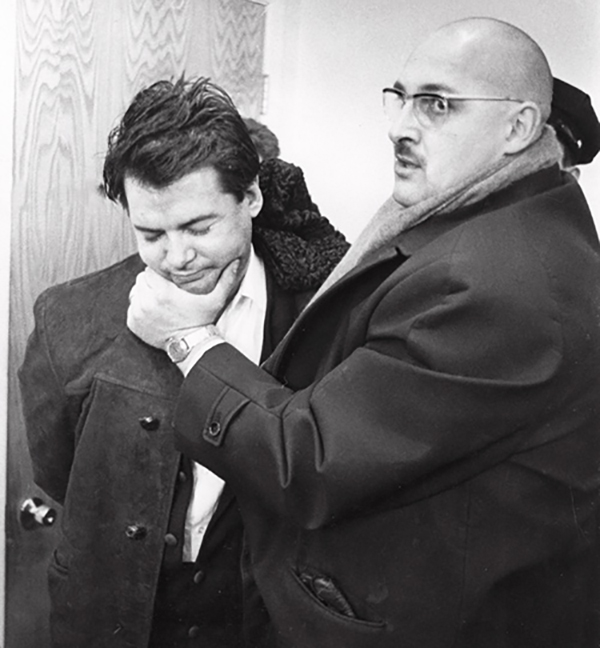

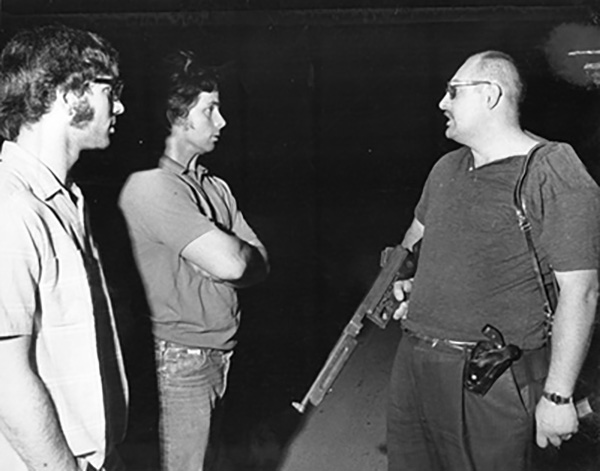

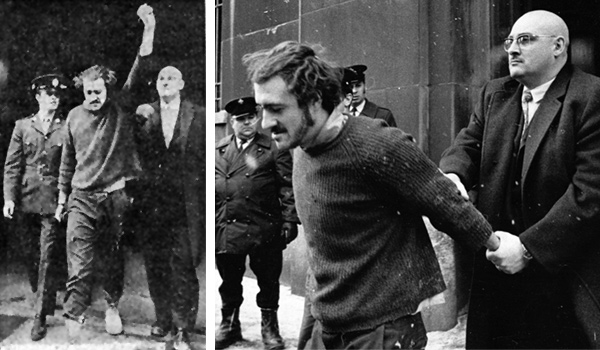

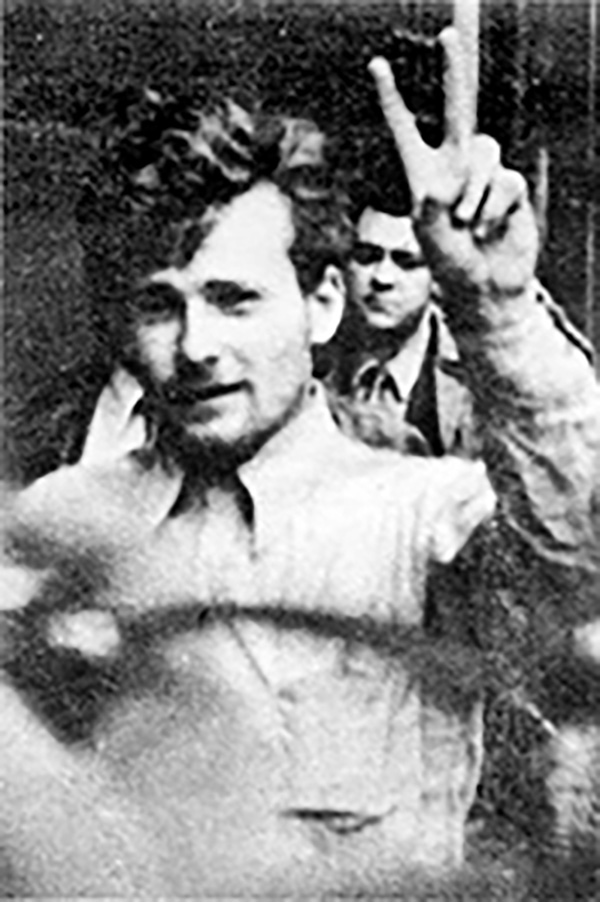

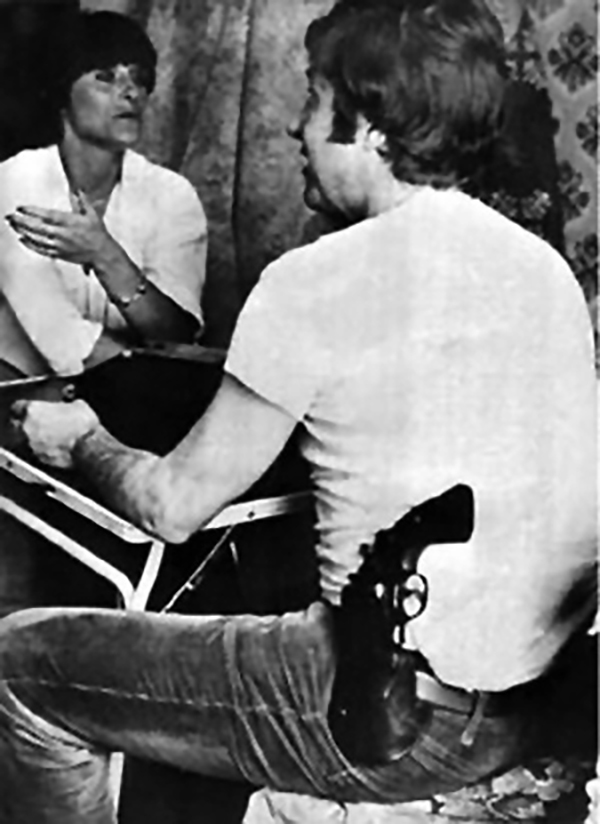

And if the brass didn’t give him full marks for his methods, certainly some citizens appreciated an old-fashioned cop. A photograph of Albert pulling down the arm of Quebec separatist terrorist Paul Rose as he tried to flash a victory salute on his way into the courthouse in 1971 was sent worldwide on the wire services. A reader from Nashville, Tennessee, cut the photo out of her local newspaper in January 1971 and sent the clipping to Albert at SQ headquarters with a note which read: “Thank you God for a man like Sgt. Albert Lisacek.”

During the terrorist crisis of October 1970, separatists in the Front de libération du Québec (FLQ), kidnapped British Trade Commissioner James Cross and murdered Quebec Labour Minister Pierre Laporte in their revolutionary efforts to separate Quebec province from Canada and to set up a socialist society patterned after Cuba. The FLQ released a communiqué at the time listing Lisacek as their No. 1 assassination target. But Albert ended up getting to them first.

After learning of the threat on his life, Albert installed an alarm with a trip wire around his country house in Lac des Écorces in the summer of 1970. The alarm sounded at 5 a.m. one morning, prompting Albert to jump out of bed and run outside “bare balls with my Thompson” looking to shoot the intruder. It seemed that a bird had tripped the wire.

Hitmen come callingThe terrorists weren’t the only ones who had him on their hit list. Albert’s current wife, Jacqueline, who is a cousin through marriage, had a disquieting conversation in the mid-’70s with her then-husband Alphonse Leroux, who was a police officer in the Montreal municipality of St. Leonard. “Three hoods have arrived in Montreal from New York to put a hit on your little cousin, Albert,” he told her. Leroux gave his wife an update three weeks later: “Little Albert is still alive, but nobody can find the three guys from New York.”

Albert knows all about bad intentions. “There are a hell of a lot of evil people out there,” he told me during one of several conversations we had before and after a June 2, 2012 shooting at the Eaton Centre in Toronto which left two dead and a 13-year-old boy with a brain injury. Through early June 2012, there had been 113 shootings and 143 victims in the Toronto area, 47 percent more than during the same period the previous year. Police say there is also high per capita gang violence in Regina, which had 600 gang members as of 2009.

Canadian gang statistics are modest compared with gang violence in the U.S. One of the lead items on the CBS Evening News of June 12, 2012 was a report on the escalating gang violence in Chicago which had 228 homicides by early June 2012, 35 percent higher than the same period a year earlier. Police estimate that Chicago has approximately 100,000 gang members, the largest such population in the U.S., and that they commit between 75 and 80 percent of the homicides in that city.

And Chicago isn’t even among the top five cities in the U.S. for gang violence. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the leading cities for gang-related homicides between 2003 and 2008 were Long Beach, Los Angeles, Newark, Oakland and Oklahoma City.

Unlike traditional Mafia activities which usually involve carefully planned individual hits on underworld figures, street gang violence often occurs in public places and involves multiple victims, including innocent bystanders hit by gunfire.

“The gangs are always trying to take over,” Albert told me. “Street crime is getting worse. I don’t know why the cops can’t clean up the street gangs. You don’t wait until they do a crime. You need good informers, like I had in my day. Get on their backs and bug the gangs until they draw a gun and then blow them away. But I guess the cops have lost control over the street gangs because of concern for human rights. They can’t work the way I did. If they could, there wouldn’t be any gangs.”

Of course, Albert knows whereof he speaks when it comes to gunplay involving criminals, his most famous and controversial case involving the shooting of Richard Blass in January 1975, six years after he was assigned to accompany Blass from his jail cell in Montreal to his bank robbery trial in Sherbrooke, Quebec, 120 miles southeast.

Blass brags he’ll escapeHis 1969 bank robbery was the first that Blass had pulled outside the Montreal area, meaning jurisdiction for his arrest and custody was transferred to the SQ and Albert, who was taking no chances, especially since Blass and eight other inmates had escaped from Bordeaux Jail just days earlier on October 16, when the prison van taking them to court was forced off the road by accomplices. Blass was recaptured within days at the home of his wife, Lise Blass, who worked as a barmaid.

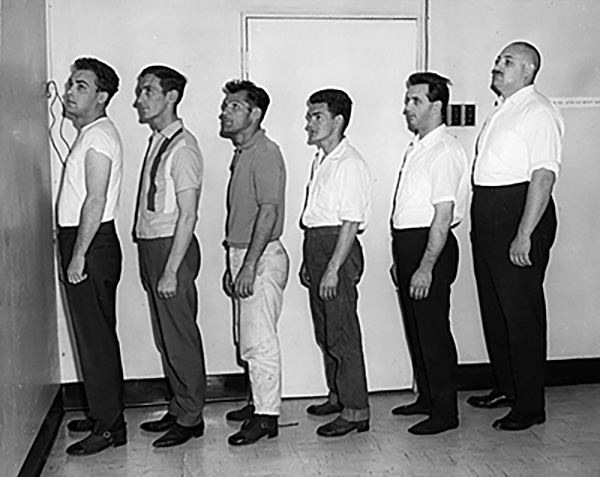

The day of their journey to the Sherbrooke courthouse in 1969, Albert handcuffed and chained the legs of Blass and his two accomplices before putting them into the police van. Blass bragged to Albert that he could count on some of his buddies to intercept the van and break him out. Morphing into his Dirty Albert persona, the burly captor matter-of-factly told his prisoner: “If they come for you, the first thing I’ll do is blow your head off. Then I’ll defend myself.” The conversation chilled out for the duration of the 2 ½-hour drive.

When they reached the courthouse in Sherbrooke, Blass’ lawyer, Frank Shoofey, complained to the judge that his client’s leg chains and handcuffs should be removed. The judge ordered Albert to comply, but the detective instead suggested that the leg chains stay on, telling the judge, “I don’t want to run after them.” The judge agreed with the detective’s suggestion.

During the one-day trial itself, there were shenanigans with a couple of Blass supporters in the back of the courtroom yelling the accused’s name and waving to him. When the court recessed, Albert and his partner found themselves in an elevator with the two Blass fans. Albert pulled a gun on them, demanding identification papers. He ordered them to be locked in the courthouse cells as “suspects”, then deflated the tires on their car so that they wouldn’t be able to follow the police van back to Montreal at the end of the day’s proceedings when he had them released.

The afternoon session went smoothly until the judge adjourned the courtroom. Albert, who had left his partner to guard Blass while he went into the corridor to stretch his legs, returned to find a big goon had pushed past the court’s elderly security guard and was leaning over the defendant’s table conversing with Blass and his lawyer.

Fearing the stranger might pass a gun to Blass, Albert grabbed him by the back of his shoulders and railroaded him through the courtroom door into the corridor where he rammed his face into the elevator door, shattering his nose.

“The guy was pissing blood like there was no tomorrow,” Albert recalls. “I told him: ‘Fuck off and don’t come back. Go to the hospital and get your nose fixed.’”

There was one incident that day which illustrated that Albert had a heart, even for a criminal like Blass, when he broke protocol by allowing one of Blass’ many girlfriends to visit with him for about 15 minutes in his holding cell at the Sherbrooke courthouse, albeit under surveillance.

Needless to say, Blass was not busted out by his buddies that day. Instead, he was convicted of the bank robbery, declared an “habitual criminal” and sentenced to four consecutive 10-year terms. The cop and the robber’s paths would cross again just over five years later after Blass escaped from prison in October 1974 and went on a deadly spree, killing 15 people in three months. In 1983, his lawyer Frank Shoofey wrote a French-language book about Blass, titled Richard Le Chat Blass, Criminel, in which he said that when the courts declared him a habitual criminal and gave him the 40-year sentence, it took away all hope and made him more desperate and dangerous.

In the meantime, Albert’s career as the most talked about cop in Canada continued to escalate between the time he transferred into the holdup squad in 1963 until 1975, after his shootout with Blass. His commanding officers were growing weary of reading about his exploits in the press.

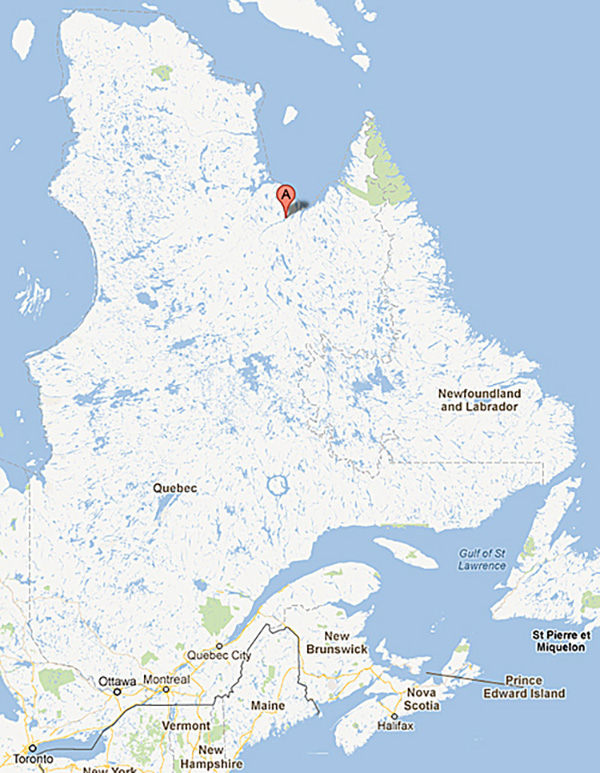

After he helped chase down the FLQ in 1970 and The Canadian Magazine article naming him the toughest cop in Canada came out in March 1972, it was suggested he transfer to a one-man post in Fort Chimo, 31 miles south of Ungava Bay in the Arctic region of Quebec, today known as Nunavik.

Albert asked his commanding officer whether there were trees that far north. No, came the answer. “Well is there grass?” No! “Well fuck it,” says Albert. “I’m a nature guy.”

If the brass couldn’t force him to transfer, they certainly had no intention of promoting him. Albert, who had attained the rank of sergeant in 1967, four years after joining the holdup squad, wrote his exams to become a lieutenant. The most famous cop in Canada, who specialized in chasing down robbers, was told that he had failed that part of the test dealing with holdups.

As befits a pariah, Albert went through partners like a lumberjack popping hotcakes. Some lasted a few months; others a couple of years. They all ended up with elevated stress levels, requesting transfers away from “that crazy bastard”. He was just too rough and took too many chances.

Terror grips QuebecBut such a man was in favour when terror gripped Quebec during the 1970 FLQ crisis. A terrorist cell called Liberté kidnapped British Trade Commissioner James Cross on October 5, 1970. A second cell called Chénier kidnapped Quebec Labour Minister Pierre Laporte on October 10, 1970. Both cells demanded the release of other FLQ prisoners who belonged to the Chénier cell and had been convicted of over 200 violent crimes between 1963 and 1970, which included robbing banks and planting bombs in English areas, such as Westmount, which left three people dead.

On October 16, 1970, Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau enacted the first peacetime use of the War Measures Act in the history of Canada, suspending civil liberties and dispatching soldiers into the streets of Ottawa, Montreal and other areas of Quebec. The next day, October 17, 1970, the Chénier cell strangled Laporte and left his body in the trunk of a stolen car abandoned at the St. Hubert airport on the South Shore of the St. Lawrence River across from Montreal.

The search for the killers of Laporte and the kidnappers of Cross went into high gear. Radio-Canada, the French-language arm of the CBC, reported at the time that 13,000 police officers and 2,000 soldiers had been thrown into the search for Laporte’s killers.

Albert was among those involved in the search for the FLQ terrorists. It was a cat-and-mouse game of police raids and the terrorists scooting between hideouts, sometimes evading capture by minutes.

Based on a tip, Montreal police led a November 6, 1970 raid on a Queen Mary Road apartment near the famous St. Joseph’s Oratory where they found and arrested Bernard Lortie, one of the four members of the Chénier cell which had kidnapped Laporte.

Unknown to police, there was a false wall in the apartment closet which concealed a secret hiding place where the other three members of the Chénier cell — Paul Rose, his brother, Jacques Rose, and Francis Simard — stayed hidden until they were able to escape through a back door the next day after the police had left.

In his 1994 docudrama titled Octobre, Quebec film director Pierre Falardeau portrayed Lisacek in uniform wrecking the apartment. Albert says he was not part of that raid and he was never in that apartment.

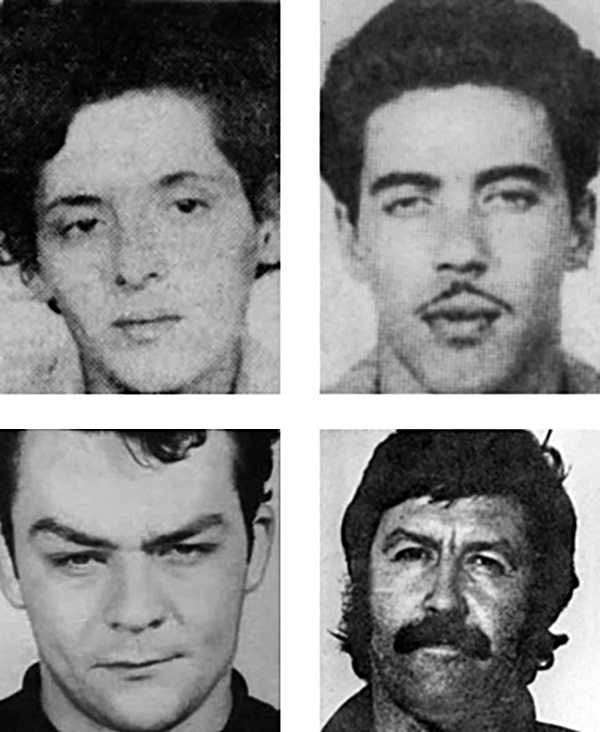

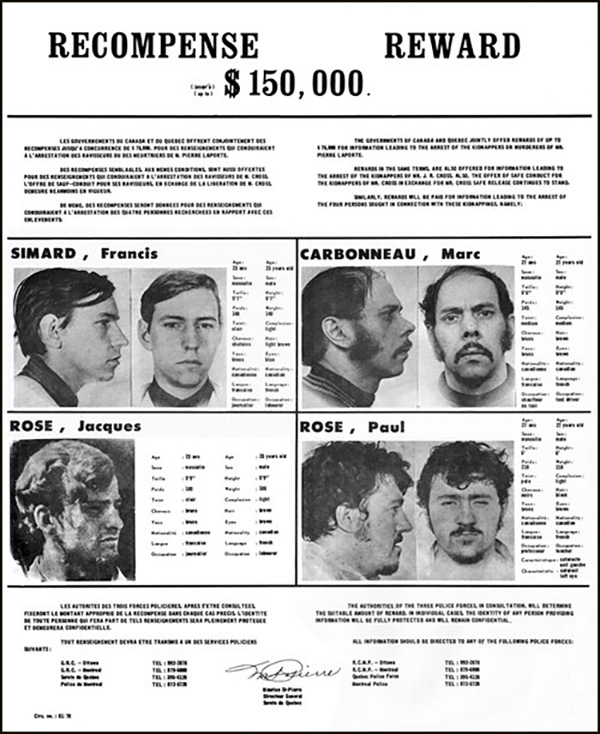

On November 2, 1970, the governments of Canada and Quebec jointly offered a reward of $150,000 for information leading to the arrest of any of the kidnappers. They issued a reward poster, which has since turned into a collector’s item, with mug shots and descriptions of the three Laporte kidnappers who had escaped capture on Queen Mary Road, as well as that of cabbie Marc Carbonneau, wanted for the kidnapping of Cross.

Blass offers to fight FLQ

As if the chaos and fear brought on by the FLQ crisis wasn’t enough to deal with, Richard Blass, serving his bank robbery sentence at St. Vincent de Paul Penitentiary north of Montreal, decided to jump into the fray. He made an offer, asking authorities to set him free so that he could kidnap some of the FLQ prisoners and hold them for ransom until Cross was released.

Of course, such a scenario made headlines in Quebec where the 5 foot, 6 inch Blass enjoyed media status akin to a rock star due to his bravado in defying authority — be it bankers, cops or Mafioso. The fact that Blass happened to be a homicidal maniac didn’t seem to bother members of the media or the public until he started killing innocent civilians after his third breakout from prison in October 1974.

Many years later, when Albert was asked about Blass’ ludicrous offer to be released so that he could help police save Cross, he answered: “No way. Did he think we were stupid?” Authorities came to the same conclusion in rejecting the offer, although Blass’ lawyer Frank Shoofey later wrote in his book that it was a sincere effort on the part of Blass, who hoped that authorities might revoke his status as a “habitual criminal” if he helped them capture the FLQ terrorists.

Meanwhile, on December 3, 1970, Jacques Lanctôt and four other members of the Liberté cell which had kidnapped Cross two months earlier negotiated his release in exchange for their safe conduct to Cuba. Police found Cross in a room in Montreal North. He told authorities that he had been tied to a chair facing a television set for the entire period, losing 22 pounds in the process.

FLQ killers caught

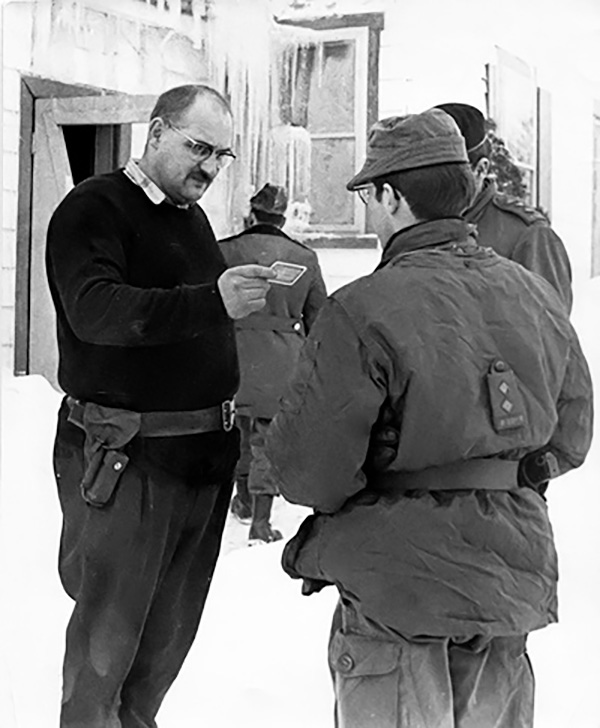

Acting on a tip on December 27, 1970, Lisacek and his SQ colleagues surrounded a farmhouse in St. Luc, 22 miles southeast of Montreal, where the three remaining members of the Chénier cell were hiding in a 20-foot-long subterranean tunnel just over three feet high.

Dr. Jacques Ferron was asked by the terrorists to act as a mediator. The negotiations stretched for hours until the Quebec government agreed to the demands of the Rose brothers and Simard that bail conditions for political prisoners “return to normal”. One last concern they had was to receive assurances from the SQ’s commanding officer that Lisacek not be allowed anywhere near them. They threatened to blow up the farmhouse if he didn’t leave. The commander ordered Albert to leave, which he did, and the prisoners came out of their hole with their hands up at 5 a.m. on December 28, 1970.

Albert is rankled to this day by the way the 1994 docudrama Octobre portrayed him shooting a Uzi sub-machinegun into the tunnel to force the culprits out. That never happened, he insists. As well, he says the film was inaccurate in showing Montreal police on the scene. Only the SQ was present.

Paul Rose, Bernard Lortie and Francis Simard were all convicted in the kidnapping and murder of Pierre Laporte. Despite the heinous nature of their crimes, none of them ended up doing much jail time:

- On March 13, 1971, Paul Rose was sent to prison for what was supposed to be life, but ended up being just short of 12 years because a Quebec commission of inquiry into the October Crisis, led by Jean-Francois Duchaine, found that Rose was not present when Laporte was strangled. Rose, the leader of the Chénier cell, was released on parole on December 20, 1982. He now works for the Confédération des syndicats nationaux, a Quebec labour union, and remains a strong supporter of Quebec sovereignty.

- Lortie was sentenced to 20 years in jail on November 22, 1971, but was released by the Canadian Parole Board after seven years. He subsequently became a successful book publisher.

- Simard was sentenced to life in prison, but was paroled in 1982, after which he wrote several books on the crisis, including one called, Pour en finir avec octobre, on which he collaborated with his three Chénier cell accomplices. It became the basis for the docudrama Octobre, which Albert says contains inaccuracies.

On May 11, 1972, a jury trying Jacques Rose for the kidnapping of Laporte declared itself hung after 15 hours of deliberations. On December 9, 1972, a second jury found him not guilty of the kidnapping after 17 hours of deliberations. On February 23, 1973, Rose was acquitted of the murder of Pierre Laporte. The Crown, which said the problem was persuading key witnesses to testify, finally had to settle for getting a conviction against Rose as an accessory after the fact in the kidnapping at a fourth trial in 1973. He was sentenced to eight years in jail in July 1973 and was released on parole on July 17, 1978.

Of the six FLQ members who kidnapped Cross, five fled to Cuba, later moving to Paris before growing homesick and returning to Quebec where they faced charges. Most did jail time of less than two years, including Marc Carbonneau who had been listed on the $150,000 Most Wanted Poster and ended up with a sentence of 20 months.

There are some interesting footnotes which indicate the high status accorded Laporte’s killers by some members of Quebec society.

- After Jacques Rose’s third trial and murder acquittal in February 1973, the French-language daily La Presse published a front-page photo of him and his lawyer Robert Lemieux drinking with several members of that jury at a hotel in Old Montreal. Lemieux, who was sentenced to 2 ½ years in prison for contempt of court during Rose’s fourth trial, was subsequently disbarred and moved to Sept-Iles, 500 miles northeast of Montreal, where he earned a living pumping gasoline, preparing legal briefs for unions and working as a matrimonial conciliator. He died at age 66 in January 2008.

- On March 22, 1978, a 42,000-name petition was made public calling for the parole of incarcerated FLQ members. Among those signing the petition were two members of the National Assembly, seven City of Montreal councilors, academics, trade unionists and entertainers.

- In December 1981, Jacques Rose received a standing ovation at the annual convention of the ruling Parti Quebecois. Premier René Lévesque, who had always eschewed violence in seeking Quebec sovereignty, later told reporters he was shocked by the display of FLQ support by his party members.

But such public support for the FLQ did not surprise Albert, who felt that a lot of French-Canadians were “brainwashed” into believing that the terrorists were heroes, fighting for the freedom of Quebec. He compares that hero worship phenomenon to the status enjoyed by Richard Blass before he went on his final killing spree in October 1974.

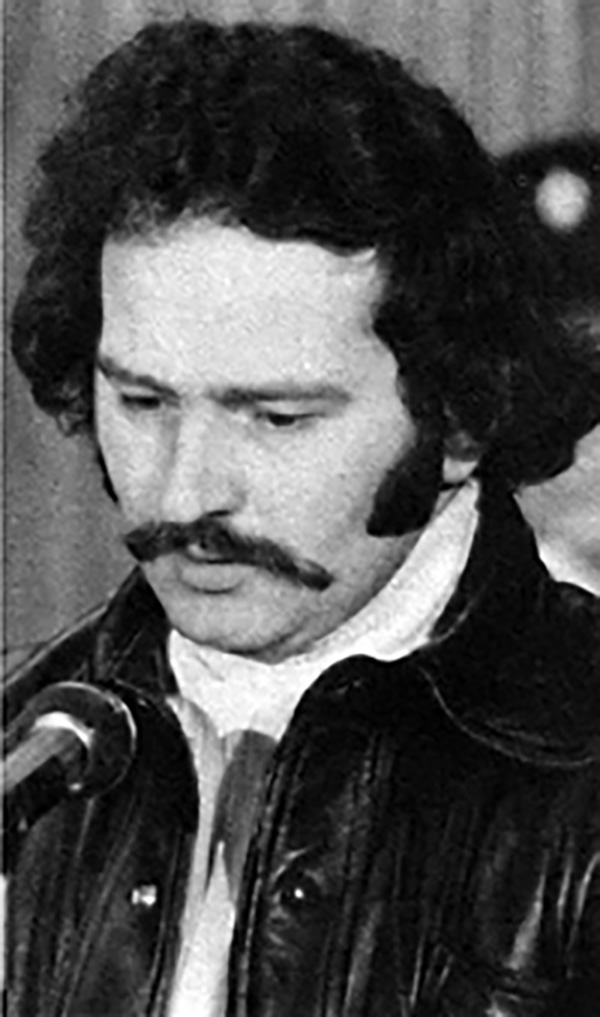

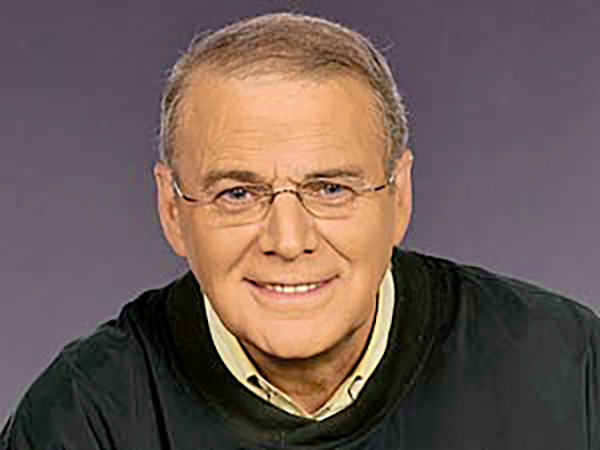

Blass is ‘chouchou’ of mediaVeteran reporter Claude Poirier, who has covered the crime beat in Quebec for more than a half century, talked extensively about Blass, the chouchou [a Quebecois term meaning favourite] of the media, in a documentary called Tout le monde en parlait [Everyone Was Talking About It] which aired in 2008 on RDI, the French-language news channel operated by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC). “He wasn’t the most intelligent….,” Poirier said. “He was a street guy who played the game….He held grudges. He’d go against gangs even if he didn’t have the weight. He wouldn’t back down from anyone.”

Blass’ heroes were Al Capone, Bonnie and Clyde, as well as Quebec bank robber and expert safe cracker Georges Lemay and Lucien Rivard, a robber and drug smuggler who in 1965 made a sensational escape from a Montreal prison, using a water hose to scale the wall. Caught four months later, he was named by The Canadian Press as Canadian Newsmaker of the Year in 1965.

Another of Blass’ heroes was Machine Gun Molly, known in French as Monica la Mitraille, a swashbuckling bank robber born Monica Proietti in 1939 on Parthenais Street, which was in the red light district of east-end Montreal and would become the headquarters of the Suréte du Quebec several decades later.

Monica, who worked as an occasional prostitute from the age of 13 to support her mother and seven siblings, had a yen for bad boys. Her husband, Scottish gangster Anthony Smith, with whom she had two children, was 17 years her senior. When he was deported to Scotland in 1962 for robbery convictions there, she took up with Montreal bank robber Vincent Tessier, with whom she had a third child.

In 1965, Tessier was sentenced to 15 years in prison for a series of armed holdups. Monica, penniless with three children to support and weighing less than 100 pounds, became the getaway driver for bank robber brothers, Gerard and Robert Lelièvre. Within a short time, she was their boss, planning the heists and strutting into banks with an M-1 semi-automatic carbine embossed with gold leaf slung against her hip. She’d fire a round into the ceiling to gain the attention of tellers and bank clients.

In 1967, her gang pulled off an estimated 20 armed robberies, netting $100,000. Nobody was killed or injured. Journalists, including Tim Burke of The Montreal Star who first dubbed her Machine Gun Molly, wrote that she would help the poor with her ill-gotten gains, becoming known as a kind of female Robin Hood.

Is it any wonder that Blass fell for her, becoming the lover of the petite Machine Gun Molly, six years his elder? That was one of the facts uncovered by Montreal journalist Georges-Hébert Germain during three years of research devoted to writing a semi-fictionalized account of Proietti’s life called Souvenirs de Monica [Memories of Monica], published in 1997.

Machine Gun Molly aims at AlbertThe triangle between Monica, Blass and Albert is a real-life example of six degrees of separation, referring to the fact that any two people on earth could know each other through six or fewer introductions. In the world of Montreal cops and robbers, the separation usually shrinks to two degrees.

When I interviewed Albert recently, he was not even aware that Blass and Machine Gun Molly knew each other. Of course, Albert knew who she was but had never chased her down because she staged her robberies in Montreal, which was the territory of the City of Montreal police.

On September 19, 1967, as he sat stopped at a red light in the north end of the city with a handcuffed prisoner in the back of his car, a vehicle bearing down at high speed from the opposite direction ran a red light and slammed into the side of a bus. Albert immediately jumped out of his car to try to help the female driver of the mangled automobile.

To his surprise, he came face to face with Machine Gun Molly, wedged and dazed behind her steering wheel, reaching for her M-1 to blast Albert. The Montreal cops, sirens wailing and red lights flashing, pulled up, jumped out and opened fire. Machine Gun Molly was dead at age 27.

A photo of the shootout scene showed one of the bullet holes through her right breast with a white lacy pushup bra visible. The irony was that Quebec’s most famous cop, considered the best at chasing down the most dangerous bank robbers, almost got taken out by one he was trying to help. The other irony, according to author Germain, was that Molly had decided that this most recent heist of $3,082 from a caisse populaire was to be her last before retiring to Florida with her children.

Even in death, the Quebec press could not let go of her. A French newspaper columnist wrote, “If Al Capone had had a daughter, he would have wanted her to be like Monica Proietti.” Eleven years after her death, the Journal de Montréal published for its Mother’s Day issue an entire page showing photos of Monica. In 2004, a feature length docudrama of her life, called Monica la Mitraille, was released based on Germain’s book.

The coincidences connecting Richard Blass, a Quebecois gangster of German-Irish ancestry, and his lover Machine Gun Molly, of Italian heritage, did not end with either her death in 1967 or his death in 1975, when he and Albert had their final showdown. On November 13, 1984, Peter (Dunie) Ryan, the leader of the primarily Irish-Canadian West End Gang and a man estimated by police to be worth between $50 million and $100 million, was shot dead by rival gangsters at his headquarters at a St. Jacques Street motel. In retribution, Monica’s old robbery partner, Robert Lelièvre, and three others were killed a few weeks later when a bomb was detonated in a downtown Montreal apartment by Richard’s older brother, Michel Blass and Yves (Apache) Trudeau, a contract killer with the Hell’s Angels. At one time, Richard Blass had also worked as a hitman for the West End Gang.

From the 1950s through 2000, Montreal was the bank robbery capital of North America. In his 2011 book titled, Montreal’s Irish Mafia, The True Story of the Infamous West End Gang, author D’Arcy O’Connor cites statistics for the first six months of 1969 — the year Blass was jailed for the Sherbrooke heist — showing that Montreal had 51 bank robberies with a 25 percent solution rate. That compared with 36 such robberies with 60 percent of them solved during the same period in Los Angeles, with its much larger population and the highest number of bank robberies in the U.S. at that time.

With the passing of Machine Gun Molly, the mantle of most high profile bank robber fell on one of her lovers, Richard Blass. His exploits were fodder for a French tabloid press hungry for colorful crime stories.

Bad boy BlassTrue to his one-time boast to a judge that no prison was strong enough to hold him, Blass and four other inmates hijacked a prison van on June 19, 1974 using a fake gun. He was recaptured a few weeks later at the home of the sister of Réal Chartrand, who had been convicted of killing a police officer in St. Thérèse north of Montreal. When he was brought before a judge to face additional charges, he wore only blue boxer shorts, his tattoos and a smile in protest against prison policy restricting showers to once weekly.

Born poor in the Villeray district of Montreal on October 23, 1945, Blass was the youngest in a family whose alcoholic, violent father, Archie Martin Blass, was at one time in the Canadian military. Richard’s father abandoned the family when he was a child.

Although he had two older brothers, Mario and Michel, both hoods, Richard was the most aggressive. He took up amateur boxing to channel his anger. When he lost one of his early bouts, he knifed his opponent and pleaded guilty to assault, spending only 15 minutes in jail. He was sent to reform school in his teens. Between 1965 and 1975, he was charged with 30 criminal offences and convicted of 23, most for robberies. He was never charged with murder because he left no witnesses behind, or if he did, they were too scared to testify.

Blass may have been a bad man, but he was a doting son, writing frequent letters to his mother, Agathe Simon, from prison. Crime reporter Poirier said in the 2008 RDI documentary that Blass “adored his mother,” herself a bar fly. Poirier went on to say: “He (Blass) once told me, ‘Don’t ever forget one thing: The only woman who won’t let you down is your mother.’” Whenever Poirier interviewed him, Blass would ask the journalist to phone his mother to pass on regards from her son.

Blass signed off his prison letters to his mother: “Your Little One who does not forget you and who loves you very much. See you soon, maman, chérie. xxxxx Richard Blass 5191.” (5191 was his prisoner number)

If the Montreal world of bank robbers was one of madness, it was also a closely-knit community. On October 23, 1974 — his 29th birthday — Blass received a visit at St. Vincent de Paul Penitentiary from his 9-year-old son, Yves, accompanied by his Uncle Thomas.

The Mesrine connectionAt the same time, Blass’ prison buddy, Jean-Paul Mercier, who was also a close associate of infamous French bank robber Jacques Mesrine, was visited by Jocelyne Deraîche, the 22-year-old mistress of Mesrine, who himself had escaped from St. Vincent de Paul Penitentiary in August, 1972 with five others, including Mercier.

Within weeks of their August 1972 escape, Mesrine and Mercier shot to death two forest rangers — Médéric Côté, 62, and Ernest Saint-Pierre, 50 — near Plessisville, about 100 miles northeast of Montreal, when one of the officials recognized them as escaped convicts.

By the end of 1972, Mesrine, a master of disguises and prison escapes, had managed to make his way back to France and was again robbing banks there, but Mercier, convicted for two other murders in the Gaspé where Deraîche hailed from, was recaptured and returned to St. Vincent de Paul, where Blass was serving his 1969 bank robbery sentence.

On that October 23, 1974 visit to St. Vincent de Paul Penitentiary, a second woman, Carole Moreau, 24, accompanied Deraîche, ostensibly to visit her boyfriend, Pierre Vincent. What authorities did not know was that Deraîche, conspiring with Moreau, smuggled in her purse two guns, handing them to Mercier, who passed one on to Blass. With hostages in tow, Blass and four other prisoners — Mercier, Vincent, along with Edgar Roussel and Robert Frappier — broke out and found a white Ford Thunderbird, waiting for them outside, where the two women had left it with the engine running.

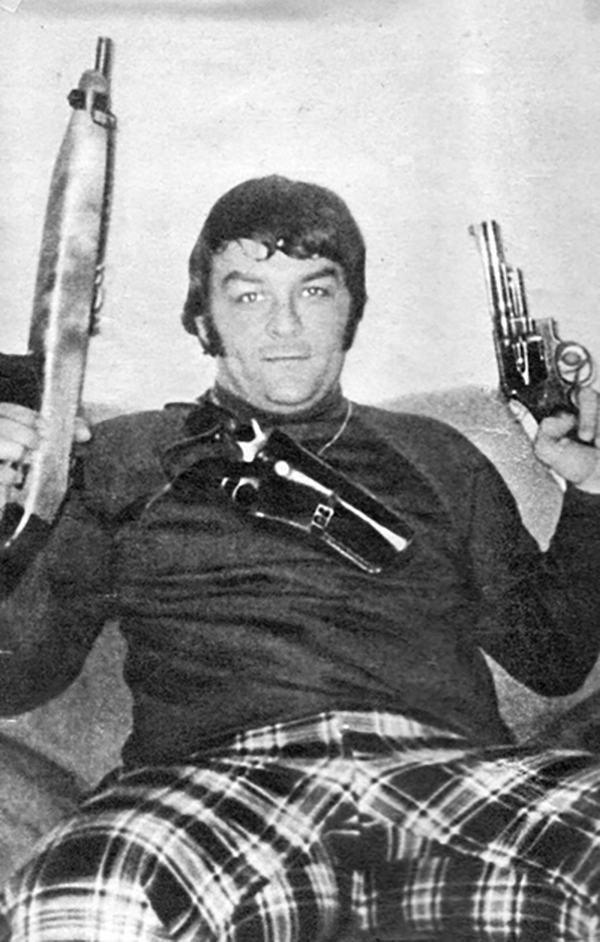

Over the next couple of months, Blass would engage in one of the worst crime sprees in the history of Quebec and Canada. But until then, he was still a favourite of the French media, with Journal de Montréal journalist André Rufiange writing Blass a message in his column after his escape asking whether he could mail a photo of himself which was better than the mug shot supplied by police. Rufiange wrote: “You’re not at your best. You look like a bandit. For the love of God, send me something better.”

Blass obliged, sending a photo of himself seated with a revolver in one hand and an automatic rifle in the other to both the Journal de Montréal and Allô Police, a crime tabloid. He sent additional photos of himself performing toiletries, watching television and relaxing.

Rufiange wrote in a subsequent column: “My request did not fall on deaf ears. Richard Blass, as much of a criminal as he is (and, as far as I know, he doesn’t deny it), has a sense of humour. After reading my column, like a good prince, he subjected himself to a photo session. See the results on this page. I thank him for his collaboration.”

Blass took advantage of his fame to write a letter to federal Solicitor-General Warren Allmand, demanding that journalists be given a tour of the special unit of St. Vincent de Paul reserved for hardcore inmates, such as himself and Mesrine, in order to publicize the despicable conditions there. Blass warned that he would kill innocent people if his demands were not met. Allmand gave in, but Blass was still not satisfied because the tour did nothing to change conditions. He wrote a second letter to Allmand warning that he would carry out his threats to kill innocent people.

Looking back at that 1974 period in his 2008 RDI documentary, crime reporter Poirier, who had known and interviewed Blass over many years, said he was warned by people who knew Blass to stay away from him because he was out of control. Even his brothers were scared of him. “He became extremely dangerous, crazy,” Poirer said of Blass. “He turned into a beast.”

On October 30, 1974, the beast attacked two ex-colleagues, Raymond Laurin and Roger “Seven Up” Lévesque, who had betrayed him by testifying for the Crown at one of his trials. Swaggering into the Gargantua Bar like a cowboy, with a firearm in each hand, he shot them dead as they drank in the bar, located in the Villeray district of his childhood.

The next day, on October 31, 1974, police received a tip that Blass’ fellow escapees, Mercier, Vincent and Frappier, were going to rob a Royal Bank of Canada branch on Jean Talon Street in the east end of the city. Montreal Urban Community Police, waiting and armed outside the bank doors, engaged in a gun battle when the crooks tried to escape, wounding and recapturing Frappier.

Mercier, wounded in the leg or arm, tried to escape but was shot a second time by police, this time in the head, as he ran away. His body was found the next day near an east-end Montreal shopping centre with a .45 pistol in his hand and an M-1 semi-automatic carbine hanging from his belt. Vincent, a convicted murderer who had also accompanied Jacques Mesrine in his 1972 prison escape, was wounded and recaptured.

Meanwhile, Blass was still free and planning the biggest one-day massacre of his life. On January 21, 1975, Blass went back to the Gargantua Bar, and fatally shot manager Rejean Fortin, an ex-cop, through the back with a .22 pistol. Fortin had only been on the job a few weeks, replacing the former manager who had retired after the killings of Laurin and Lévesque three months earlier in the same bar.

Blass then shot and wounded another man trying to escape. When Fortin’s wife arrived to pick up her husband, Blass herded her and 11 other witnesses, including the wounded man, into a room four feet by eight feet used to store beer. Aided by his cousin and a close friend of his brother Michel, Blass locked the door and barricaded it with the jukebox before setting fire to the bar. In total, he killed 13 people that night, but he did let some bar patrons leave, including his friends, members of his gang and people he judged to be “okay”.

Mesrine’s mistress turns on BlassThe killings shocked the public and elected officials. Even Jocelyne Deraîche, who had helped smuggle the guns to break Blass out of prison and served 20 months in jail for that crime, turned on him. Her true feeling were revealed in an undated note, obtained by a French auction house, which she wrote, possibly to her lover Jacques Mesrine, the notorious bank robber and killer wanted in both France and Quebec, where he had served time in St. Vincent de Paul Penitentiary with Blass.

Deraîche writes that she was “really angry” when she heard of the Gargantua Bar killings: “I sent Blass a missive expressing my hatred and repulsion for the sickening massacre at the Gargantua Bar…a massacre which occurred shortly after I helped break him and four of his friends out….Richard Blass, called The Cat, asked me several times to pardon him, but how can one pardon such a massacre!”

Crime journalist Poirier and Blass’ lawyer, Frank Shoofey, would later say that Blass was as good as dead after he pulled off the Gargantua Bar massacre. They believe that the police had no intention of taking him alive after that incident. In the 2008 RDI documentary, Poirier said Blass enjoyed playing “cat and mouse” with the police, especially Lisacek. “This policeman (Lisacek) who had the reputation of being the toughest cop in Canada would do anything to stop him (Blass),” Poirier said.

For his part, Albert nows says he thought of Blass as “a jerk who had to be stopped”, but that he didn’t chase him down with the intention of performing an extrajudicial killing. Within three days of the Gargantua Bar massacre, Albert says there was a break in the case when Montreal police doing surveillance of a crook named Benoit Vinet saw another man fitting Blass’ description run out the back door of a house in the Rosemount district of Montreal and jump in to the back seat of Vinet’s waiting Buick.

Just after 1:30 a.m. on the morning of January 24, 1975, Albert was awakened by a call to lead the raid against a suspect fitting Blass’ description who had been followed in the Buick to a luxurious chalet in the Laurentian ski resort of Val David, 50 miles north of Montreal.

At about 4 a.m., a combined squad of SQ and Montreal Urban Community police detectives had surrounded the chalet, located on a hillside. When they saw the lights go out just before 4:30 a.m., the detectives made their way up the slippery, snow-covered slope. Five of the detectives surrounded the chalet, while three others — Det.-Sgt. Albert Lisacek from the SQ, Det.-Sgt. Jacques Durocher of the Montreal Urban Community Police and Cpl. Marcel Lacoste of the SQ — headed up the stairs to the front door, carrying their sub-machineguns.

The last night of his lifeWhat happened next has been a subject of controversy in media and law enforcement circles for years. Lacoste testified in February 1975 at a coroner’s inquest into the death of Blass that he broke the window of the front door with the butt of his sub-machinegun. He testified that he saw Blass’ blonde companion, Lucette Smith, in a negligee at the foot of a staircase leading to the second floor and that he yelled for her to come out or he would shoot. She said twice, “Let me out.”

Lacoste testified that he asked Smith whether Blass was in the chalet, and she pointed to a bedroom at the back on the ground floor. Both Lacoste and Durocher testified that the three detectives walked towards the bedroom where they saw Blass holding a .357 Magnum revolver in his right hand. Both detectives testified that Lacoste’s gun initially jammed and Durocher started firing immediately at Blass, joined within seconds by Lacoste, who had managed to get his gun working. Both detectives were firing 9mm Smith and Wesson sub-machineguns.

Durocher testified at the coroner’s inquest: “….There was no hesitation when I saw he (Blass) had a gun in his hand….I opened fire. It wasn’t time to start asking questions. I let go a burst of machinegun fire and saw Cpl. Marcel Lacoste was having problems with his machinegun, so I jumped to the side and fired again. By the time I stopped shooting, Lacoste’s gun was no longer jammed because he was also shooting.”

There were 27 bullets fired from two different angles by Durocher and Lacoste which slammed into the killer’s chest, head, legs and wrist, their force wedging his 180-pound body supine in the closet, with blood oozing from his wounds.

At the time, Blass’ lawyer, Frank Shoofey, did not accept that the shooting of his client by Durocher and Lacoste was a case of self-defense. He questioned why Blass, a lefty, would be holding a revolver in his right hand, as indicated by the testimony of Durocher and Lacoste. He concluded that his client had wanted to give up, but instead had been executed.

Now, 37 years later, Albert told me in our interview that after Smith opened the door and let police in, the detectives saw Blass in the living room about 10 feet from the front door, walking towards them partially dressed, unarmed and holding a sock in one hand. He refused to discuss how Blass ended up in the bedroom with Durocher and Lacoste firing on him, saying only: “If possible, I would have preferred to bring Blass in alive.”

Questions lingerAlthough most of the media reported that Albert had killed Blass, and, in fact, Albert received a death threat in the days after Blass was killed, it became clear at the coroner’s inquest that it was Durocher and Lacoste who fired all the shots. One wonders why Albert, who had extensive experience and expertise with a sub-machinegun, was the only one of the three detectives not to shoot Blass. One also questions why Albert was the only one of the three detectives not subpoenaed to testify at the coroner’s inquest into Blass’ death in February 1975. Could it be that the establishment would not have wanted to hear what the outspoken Albert might have testified under oath?

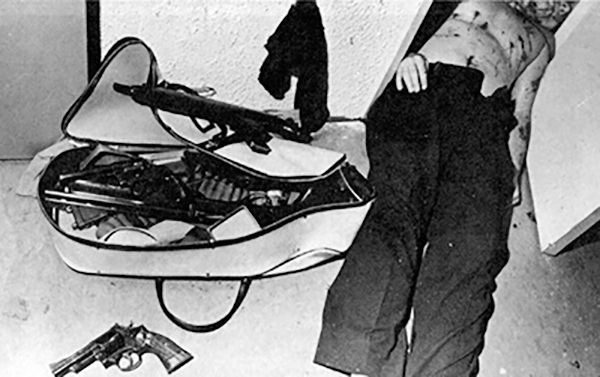

I am also left to ponder why if Blass wanted to shoot it out with the cops, he did not use his M-1 semi-automatic carbine, capable of rapid fire and with a clip of 20 bullets, rather than a .357 Magnum revolver with six bullets fired one at a time. And if Blass really wanted to shoot the cops down that day, why didn’t he open fire on the detectives with his M-1 as they entered the house when they were at their most vulnerable? None of the detectives was wearing a bullet-proof vest, according to Albert. Among the firearms found in a bag in the chalet bedroom were the M-1, a .38 special revolver, a .22 revolver, a 12-gauge shotgun with the stock and barrel shortened and a .455-calibre Colt revolver. Gas masks and extra ammunition were also found.

Journalist Poirier weighed in on the subject in the 2008 RDI documentary when he said that Blass knew he was completely surrounded at the chalet and had no way out. “He was a guy who loved publicity so much, he would have been happy to make a statement and to use the media,” he said. “They (police) conducted his trial in the chalet.”

Albert was the only one of the three detectives still alive in 2012 to say what happened in that chalet in 1975. Durocher died at age 43 on June 18, 1976 when his car went off the road at 2 a.m. near Quebec City. The Montreal Gazette reported at the time that he was returning home from a business trip. A 20-year-old woman, who was a passenger in his car, was injured but survived. Lacoste died of a heart attack at age 65 in 2008.