Updated: date

Published: April 2012

Little known mass execution at Balf comes to light

A bullet through the head and four more to the body can’t silence Hungarian survivor of Nazi massacre

By WARREN PERLEY

Writing from Montreal

Editor's Note: Duddy Alt passed away June 18, 2013, 14 months to the day after we first posted the story of his amazing survival of The Holocaust.

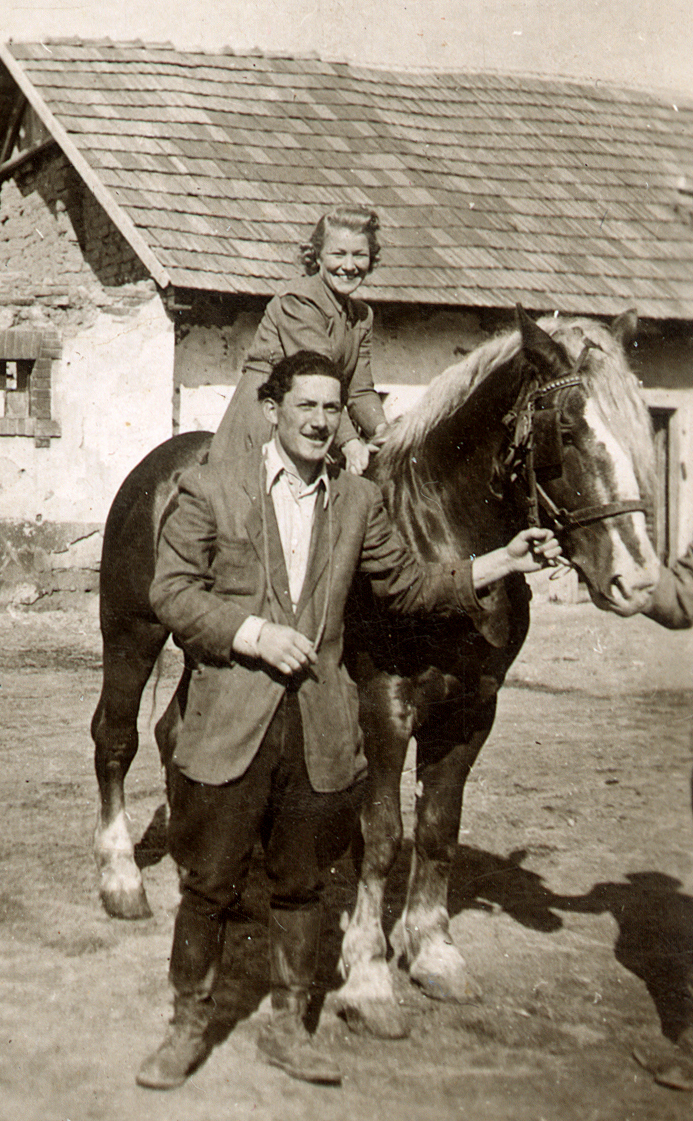

Duddy Alt, 22, is athletic, strong and scared. It is dank and dark at 5 a.m. on this pre-dawn Monday of November 27, 1944 as he and about 50 other Jews huddle in a Budapest cloister trying to avoid capture by the Nazis.

Alt, a bodybuilder since age 10 and an avid soccer player, knows the jig is up. He has been on the run for more than a month from an Hungarian army labour camp and is carrying false identity papers. His older sister, Roza, her husband, Ignac Keller, and their son, Andrew Keller, are among those being hidden by the nuns.

All to no avail. An informer has betrayed their hiding place to the Hungarian police and to the dreaded Nazi SS in their distinctive, Hugo Boss-designed “feldgrau” wool gray tunics with the gray-silver Waffen SS collar insignia embroidered on black wool.

“Waffen” in English means “arms” or “weapons”, and these SS troopers have the firepower — standard issue Mauser Karabiner 98 kurz rifles, better known as a K98. With a range of 500 metres, it is known for its accuracy and velocity.

Resistance is futile. Alt and his 50 brethren walk out of the nuns’ residence in surrender, surrounded by the armed troops. Their crime? They are Jews. The men and women are separated.

The males, including Alt, his 17-year-old nephew, Andrew Keller, and Andrew’s father, Ignac Keller (Alt’s brother-in-law), are taken to a train station for a six-day, 207 kilometre journey in cattle cars to a labour camp in Sopron, a western Hungarian town near the Austrian border. The women are put on a train for Auschwitz-Birkenau, one of six Nazi death camps in Poland.

Alt was one of an estimated 650,000 to 725,000 Jews living in Hungary in 1941 when an alliance between Nazi Germany and Hungary was forged.1 Between 120,000 and 260,500 of them — most from Budapest — survived the Second World War.2

Hungary, under its regent (head of state) Admiral Miklós Horthy, had forged the alliance, joining the June 1941 invasion of the Soviet Union in exchange for a promise that Hungary would have certain lands lost in the First World War restored to it by Nazi Germany.

But in March 1944, German Führer Adolph Hitler turned on Horthy, accusing him of not being a loyal ally and of not being tough enough on the Jews. On March 18, German tanks entered Budapest and Hitler installed a puppet government under Dome Sztójay. Conditions immediately devolved into death and anarchy for Hungarian Jews.

By July 1944, less than four months later, more than 400,000 Hungarian Jews had been deported in cattle cars to the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp in Poland where they were gassed. Alt’s father, Ignac, was among them.

Wikipedia, the open source, online encyclopedia, reports the deportation of the Hungarian Jews to Auschwitz-Birkenau, beginning on May 15, 1944, in these terms:

SS Colonel Adolf Eichmann, whose duties included supervising the extermination of Jews, set up his staff in the Majestic Hotel and proceeded rapidly in rounding up Jews from the Hungarian provinces outside of Budapest and its suburbs….The devotion to the cause of the "final solution" of the Hungarian gendarmes surprised even Eichmann himself, who supervised the operation with only twenty officers and a staff of 100, which included drivers, cooks….According to Winston Churchill, in a letter to his Foreign Secretary dated July 11, 1944, "There is no doubt that this persecution of Jews in Hungary and their expulsion from enemy territory is probably the greatest and most horrible crime ever committed in the whole history of the world….”

In October 1944, the Arrow Cross Party, an extremist pro-German political group, took power in Hungary, vowing to deport the few remaining Jews, who lived in Budapest. Alt was among them.

Historian confirms massacre of JewsMihály Csató, an historian with the Hungarian government-funded Holocaust Memorial Center in Budapest, told beststory.ca that from November 1944 until the end of the war “tens of thousands” of Jews “ were deported to the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp, most of them old men and women. The more able-bodied men were dragooned as forced labour to dig tank traps and dykes in the frozen ground.

Known as the “Südostwall,” the lines of ditches were meant to trap Soviet tanks which were advancing from the east through Hungary, towards Germany. Csató described it as an unrealistic plan. “There weren’t enough raw material and human resources to do it,” he said in an interview.

Between the time of Alt’s arrest at the cloister in Budapest on November 27, 1944 and the end of the Second World War in early May 1945, these frenzied Arrow Cross Party extremists and their Nazi allies were intent on wiping out every Hungarian Jew and razing that country’s infrastructure — rail lines, roads and communications — before surrendering to the Allied forces. For example, Csató says the killings in Hungary continued until May 2, 1945 when a group of Hungarian Jews was wiped out in Hofamt Priel.

Alt tasted death on Saturday, March 31, 1945 as one of the victims in the massacre of 183 Jews in Balf, which at the time was an Hungarian village next to the town of Sopron where he had been deported after his capture four months earlier in Budapest. (Since 1986, Balf has been administratively part of the town of Sopron.)

More than 66 years have passed since the end of the Second World War. Alt is one of the last survivors who can bear eyewitness testimony to the horrific Nazi extermination campaign against the Jews.

Now living in Montreal, Alt who celebrated his 90th birthday on October 21, 2012, still looked strong and athletic as he sat ramrod straight in an armchair and recounted every detail of his near-death experience on that Saturday in March 1945. His only visible concession to age is a wooden cane for balance when he walks.

When they arrived in the western Hungarian town of Sopron in early December 1944, Alt recalled in an interview, he and the others captured in the cloister near Budapest were joined by thousands of Jewish men arrested throughout Hungary.

Among them was another brother-in-law, Danny Lebovics, who was married to his sister Manci. All had been forced at gunpoint by the Nazis to dig ditches to stop the wave of Soviet troops and tanks counterattacking the collapsing German military lines throughout eastern Europe.

Csató, the historian with the Holocaust Memorial Center in Budapest, says “tens of thousands” of Hungarian Jews who, like Alt, were part of the forced labor died under “inhuman conditions” in the winter of 1944-45. “There were also massacres and killings because of anger and (for the) pleasure of the soldiers,” Csató told beststory.ca in an email interview. “These killings continued until the end of the war.”

Alt remembers the horrors as though they happened yesterday. “The Nazis stuffed us in barns — maybe 30 to 50 per barn — with one Jew in charge of making sure the others didn’t escape,” he recalls. “If one Jew went missing, the responsible Jew would be shot. We were sick and starving.”

Beatings were common. Food — all of it foul-tasting — was scarce. Ice-chilling winter temperatures entombed the barns where the men shivered in the dark every night before heading out at dawn to dig more ditches until nightfall.

With the Soviet troops closing in, the Germans decided to retreat, force-marching those prisoners able to walk back towards the Mauthausen-Gusen labour camp in Austria.

But for those too sick to march, they had different plans. Csató said “183 invalid and sick Jewish men” were killed just outside Balf “by the retreating SS military police” on Saturday, March 31, 1945.

Alt, suffering a high fever and chills from typhus, was one of the “sick” Jews, unable to walk back to the German lines.

Death was the only way outThe prisoners, who could hear the sound of Soviet tanks and planes nearby, were hopeful that the war would end soon with a Nazi defeat. But for most of them, the only way out was death by execution. Four days running, March 28 through March 31, 1945, Nazi SS guards arrived at the barns, taking away the prisoners and splitting them into two groups — those healthy enough to walk back to the German lines in Austria and those too sick to walk a long distance.

On Saturday, March 31, they came in the morning for Alt, his two brothers-in-law and his nephew — 187 “sick” Jews in all. Alt calls it “The Last Day.” The SS guards told the prisoners that they were going to the nearby village of Balf to do “a little work. “

Alt’s 17-year-old nephew, Andrew Keller, managed to hide in a bathroom near the barn and eventually made his way to Budapest, leaving 186 Jews to face their fate. The rest of the prisoners, including Alt and his two brothers-in-law, were marched through the snow, some in bare feet.

What they found in Balf were thousands of German soldiers in nearby fields with about 10 members of the SS standing over ditches — between three and four metres deep — dug about two kilometres outside Balf.

The 186 Jews, including Alt, were told to climb down into the ditches. There was nowhere to run. One by one, the SS started shooting the prisoners standing below them in the mud. Alt, half delirious from fever, heard the staccato gunshots on each side of him as prisoners took one or more bullets to their upper bodies and fell into the slime.

He knew what was happening, but was powerless to do anything to save himself , his two brothers-in-law, Danny Lebovics and Ignac Keller, or any of the others. “’Why me, why me?’ I kept thinking. Next to me were my brothers-in-law with wives and children. Then all the others….” His voice trails off.

As he saw the bodies falling to the right and left of him, Alt says he remembers thinking: “I just want to get through this as fast as possible. Let’s finish it already. I wish it was over.”

Then it was Alt’s turn. The first bullet slammed into his forehead over his left eyebrow and exited the side of his head. The SS started banging rocks against the supine bodies that lay in the ditch. If there was a twinge, they shot them again. When they bludgeoned Alt’s head, his body jerked. So the SS pumped two more bullets into Alt’s right arm and two more into his left leg.

The tough Jewish weightlifter — the youngest child in a wealthy pre-war family of four brothers and four sisters — was dead, or so the SS thought. Alt says he was somewhere between life and death.

“I was half conscious after I was shot,” Alt recalls. “I was in a beautiful park with flowers. I’m sure I had never been in that place before. I started to believe that I was in the afterworld. I dreamed that I left my body and then came back.”

When he regained consciousness three hours later, he heard Soviet soldiers cursing the Germans and yelling in Russian at the corpses to determine whether anyone was still alive. Alt’s right eye blinked. The Soviets had a miracle survivor on their hands. They found two more breathing among the 186 shot that day — leaving a single day massacre toll of 183 dead and three wounded.

Four of the five bullets had exited Alt’s body, leaving him with one bullet in his left leg. His right wrist was shattered where one bullet had passed through.

With help from the Russian soldiers, Alt climbed out of the ditch, wrapped his leg wound in a scarf he was wearing and walked two kilometres to the Soviet camp in Balf, where a female Russian soldier bandaged his wounds.

The Russians gave him and the other two wounded men a horse and buggy to go to St. Margarite Hospital in Csorna, 20 kilometres away. A German national, who had been sequestered by the Russians, was instructed to drive the buggy with the three wounded men.

A short distance out of town, the German jumped from the buggy and ran away, leaving Alt to guide the horse and buggy. About one hour later, they came across a Russian solder with a badly limping horse. The armed Russian grabbed Alt’s horse, leaving him the lame one. Alt was grateful not to be shot in the encounter.

He and his two companions slept in the forest that night. The next morning they saw in the distance a group of Ukrainian soldiers in Soviet uniforms coming towards them. Alt hid the limping horse and buggy.

When they got within speaking distance, Alt asked in Russian for some food and water. Things looked promising until Alt let some Yiddish words slip into the conversation and the Ukrainians noticed the yellow star on his labour camp clothing.

”Fucking, dirty Jews,” Alt recalls them yelling. He and his comrades looked too close to death for the Ukrainians to bother exerting themselves to finish the job.

Three corpses and a limping horseAlt recovered his hidden horse to continue the journey to Csorna, which should have taken a few hours. Instead, the journey took one week.

“When we arrived at Csorna, people looked at us and said: ‘What the hell is that? A buggy with three corpses and a limping horse.’ “

Alt told an Hungarian policeman that they were starving and asked for some milk. No problem, but the price for the milk would be the limping horse and buggy. Alt made the deal.

Arriving at the hospital in Csorna, he was greeted by Hungarian nuns and a Russian doctor, who took him into the emergency room where he cut off Alt’s bloodied, bacteria-encrusted clothing and burned it.

The young doctor cleaned and wrapped Alt’s head and wrist wounds, immobilizing the wrist with a piece of wood. The leg was more complicated because the bullet was still embedded.

The doctor wrapped a piece of gauze around the head of a knitting needle and slowly pushed the bullet, inch by inch, through the patient’s engorged flesh until it squeezed out the other side of his leg. There was no anesthesia available. Alt passed out from the pain.

Fearing infection could take hold in the leg, the doctor repeated the treatment every second day for about one week, pushing a knitting needle wrapped in clean gauze through the wound until only oozing blood could be seen with no sign of pus.

The doctor’s concern for infection was well founded. One week after arriving at the hospital, one of the other two men — in his 20s — who had survived the Balf massacre died of infection and blood poisoning from an arm wound.

The third man had been grazed in the head by a Nazi bullet, which passed from front to back without penetrating his skull. One week after arriving at the hospital in Csorna, Alt remembers the man walking away.

Alt’s recovery was slower. After six weeks, he could walk with the help of a crutch. He donned the Russian hat, coat and black pants which the hospital had provided to him and walked, “looking like a scarecrow,” to the train station where he boarded for Gyor, the nearest big town.

There he found a Jewish refugee organization called HIES, which provided a bed and got him train fare for Budapest, where he arrived in May 1945, finding it “in shambles” with no public transportation system. Everywhere he walked, he was surrounded by Jewish residents asking him whether he knew of any other survivors of the Nazi massacres near Balf.

One of his first stops in Budapest was the Jewish Hospital, where a doctor shook his head in disbelief that Alt had survived both his wounds and the treatment he had received from the Russians in the hospital at Csorna.

Doctors at the Jewish Hospital in Budapest took X-rays and put his right wrist in a cast, but there were too many bone chips for them to restore mobility.

While still recuperating in the Budapest hospital in 1946, Alt was summoned by the father of one of the victims of the Balf massacre who was now in Alt’s words “a big shot in the Hungarian government.”

The government official arranged to have all the bodies exhumed from the mass grave next to the stone wall of the Catholic church in Balf, where the Soviet soldiers had buried them after discovering the Nazi massacre.

Alt was given the traumatic task of identifying each of the bodies of his fellow prisoners as they were exhumed from the ground so that they could be reinterred with proper identification in the Neolog Jewish cemetery in Budapest.

Body and soul were shatteredThe war took a high personal toll on Alt. His body and soul had been shattered. All his family had been incarcerated, either through forced labour or in concentration camps.

Three of the four brothers, including Duddy, and his four sisters managed to survive, although his eldest sister, Roza, who was sent to a concentration camp after being captured with Duddy on November 27, 1944, died in hospital a year after the war ended.

Duddy’s brother, Bela, and his father, Ignac, were killed by the Nazis, as were his two brothers-in-law, Ignac Keller and Danny Lebovics, who were executed at Balf. Duddy’s mother, Rosa, who had been incarcerated in a Nazi concentration camp, died of colon cancer within two years of the end of the war.

After one year recuperating in Budapest, Duddy — seeking to rebuild his life away from the horrors of Hungary — immigrated to what would become the independent state of Israel in 1948. Still under British mandate and known as Palestine at the time of his arrival, he was joined by his nephew Andrew Keller, who had escaped just prior to the Balf massacre. Duddy’s brother, Immanual, who spent three years in a Soviet prisoner of war camp after being captured near Stalingrad as part of the Nazis’ forced labour, also moved in 1947 to the future Israel before relocating to Australia in 1956.

Duddy immigrated to Montreal in 1958 to join his three sisters — Szeren, Manci and Jolan — and his brother Miklos, who had moved to this city two years earlier. Descended from three generations of well-to-do livestock dealers and landowners in Hungary, he still had the entrepreneurial fire burning in his belly. So with an Israeli partner, he opened a knitting mill called Hudon Knitting.

After one year, Duddy bought out his Israeli partner and brought in his nephew, Andy Lebovics — the son of Manci and Danny, who had been executed at Balf. For the next 29 years, they prospered, expanding their knitting mill into dying operations.

He and his first wife, Suzan, who was Hungarian, had a son, Thomas, a mechanical engineer who lives in Thornhill, Ontario. Suzan died of a heart attack in 1975. In 1986, Alt remarried an Israeli named Shifra Salzer.

Retired since 1991, Alt says he still sometimes has the recurring dream of the beautiful park with flowers that he had the day he was shot through the head by the Nazis in March 1945.

Current Jewish life in HungarySince then, Alt has been back to Hungary once — for a 1992 memorial reunion in Balf — where he was asked to speak and he voiced his opinion, employing blunt language, that he did not believe that Jews could ever live again in safety and dignity in that country.

The Institute for Jewish Policy Research (IJPR) published a study in September 2011 which concluded that since the collapse of communism in 1990-91, the Hungarian Jewish community has been “re-invigorated” although it is “facing the challenge of low engagement in communal life.” The study says that “only 10 percent of the Jewish population is affiliated to any Jewish organization.”

The IJPR is a London-based research institute and think-tank which specializes in contemporary Jewish affairs in Britain and other European countries. Their study of Hungarian Jewry was one of four sponsored by the Rothschild Foundation (Hanadiv) Europe on how Jewish communities in Hungary, Poland, Germany and the Ukraine have fared since the advent of democracy and European integration following the fall of communism two decades ago. The studies on Hungary and Poland were released in September 2011. The other two were to be published in 2012.

The IJPR cites Jewish population figures for 1941 — the last census before the Holocaust — similar but less than those figures provided earlier in this story. The IJPR says the 1941 census showed there were 400,000 Jews “of the Israelite persuasion” and another 50,000 to 90,000 “baptized Jews” living in the “territory that constitutes Hungary today.” The New Jewish Encyclopedia, quoted earlier in this story, put the pre-Second World War population at 650,000 Jews, while the U.S. Library of Congress cites 725,000 Jews living within Hungary’s expanded borders of 1941. Again, the discrepancies are likely due to shifting borders and definitions as to what constitutes a Jew.

The definition of what constitutes a Jew in Hungary is still a contentious issue, according to Jewish law. Under Orthodox and Conservative Halacha (Jewish law), a child born to a Jewish mother and a non-Jewish father is considered a Jew whether brought up in the religion or not. However, a child born of a non-Jewish mother and a Jewish father is not considered a Jew. But under Halacha practiced by Reform Judaism, a person born of either a Jewish father or mother is a Jew, but only if that person is brought up as a Jew.

Leaving aside for the moment the question of what constitutes a Jew under Jewish law, the IJPR’s Hungarian study estimates there are currently between 80,000 and 150,000 people in that country who have at least one Jewish parent. Using the broader criteria of having at least one Jewish grandparent, the figure rises to 160,000 adults over 18 years of age and more if the under-18s are included. About 90 percent live in Budapest. Those figures give Hungary the biggest population of Jewish descent in post-Communist Europe outside the countries of the former Soviet Union.

By comparison, the IJPR estimates that Poland now has a Jewish population of between 8,000 and 15,000, compared with more than 3 million prior to the Second World War. Jewish culture in the last two decades, as evidenced by the establishment of the private, 300-student Lauder school in Warsaw, is trying to survive in a less than supportive environment.

A survey published by the American Jewish Committee in 2005 indicated that 56 percent of Poles agreed that “Jews have too much influence in the world” — the highest response in all the European countries polled. The IJPR interprets these findings as meaning that even if attitudes in Poland have improved, “some basic anti-Semitic stereotypes remain unchanged.”

Although the IJPR study on Hungary makes clear that Jewish culture in that country has enjoyed a renaissance since the fall of communism two decades ago, it faces the challenge of attracting more participation in community events. Written by Prof. András Kovács of the Central European University in Budapest, and Aletta Forrás-Biró, an assistant professor at the School of Psychology and Education of the Eötvös Loránd University in Budapest, the study calls for:

- Restructuring of the Hungarian Jewish infrastructure to ensure that decisions affecting the community are made in a democratic and transparent fashion;

- Help to build a religiously pluralistic communal environment;

- Greater levels of cooperation among Jewish community groups.

The IJPR cites as one of the major achievements of the last 20 years for the Jewish community of Hungary the signing of key contracts with the Hungarian state calling for compensation for Jews who were persecuted in the past and had their possessions confiscated. As well, it lauds the Hungarian government for subsidizing the Holocaust Memorial Center, which was established in 2004, and for introducing into schools in 1999 an annual Holocaust Memorial Day.

Looking back, Csató of the Holocaust Memorial Center in Budapest says many prominent people of the Hungarian intelligentsia died in the Balf massacre, to which Alt bears witness. The labour camp in Balf existed from December 4, 1944 until March 31, 1945 — the day of the massacre, he added.

In all, about 8,000 men and women died in the winter of 1944-45 at Balf and other villages in the area where there was forced labour of both Jews and Christians, Csató said.

In 2008, the Hungarian government erected a new monument in Balf to the victims of the Nazi’s 1944-45 forced labour camps, which it commemorates every year on December 4th, Csató says.

The slide into Nazi oblivionA little less than a decade before Nazis began killing six million Jews in European death camps in 1941, the enabling event occurred which allowed such state terror to be implemented — Hitler’s transformation of Germany from a democracy, with constitutionally protected rights, into a dictatorship with absolute power in his hands.

By the early 1930s, there were 6 million unemployed Germans and millions more underemployed out of a population of 66 million, and they were more concerned with finding a way out of the hyperinflation and unemployment of the Great Depression, that had started in 1929, than with preserving democracy. They rallied to Hitler’s call to renounce the onerous reparations imposed on Germany by the victorious Allies after the First World War. They could live with Hitler’s anti-Semitic campaign rants if that was the price for a messiah to lead them out of their economic desolation.

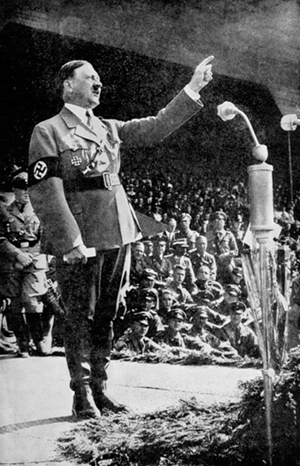

Hitler, in control of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (commonly known in English as the Nazi Party), promised that if elected president in the March 1932 election against incumbent President Paul von Hindenburg he would put an end to the Communist Party in Germany and would eliminate unions. In a speech to big business leaders at the Industry Club in Düsseldorf on January 17, 1932, he promised them a free hand in a massive public works and rearmament program if he was elected.

In his masterful 1976 biography titled, Adolf Hitler, Pulitzer Prize-winning author and historian John Toland writes of Hitler’s speech to the business elite at the Industry Club:

Rarely had Hitler spoken so effectively, alternating between emotion and logic. In one moment he shook his listeners with terrible visions of Bolshevism and the end of the system that had brought them security; in the next he appealed to their selfishness: if they wanted their industrial complex to survive and expand they would need a dictator at the helm of government, one who would eventually lead Germany back to its position as a world power. His listeners could visualize 50 years of accomplishment and wealth dissipating, and many went home prepared to contribute considerable sums to the man who promised to save them.3

Hindenburg, with 53 percent of the popular vote, was re-elected president by more than 5 million votes over Hitler. However, in subsequent elections for the Reichstag (parliament) on July 31, 1932, the Nazi Party won 13.7 million votes, half a million more than the combined totals of their closest rivals — the Social Democrats and the Communist Party — which represented 37.3 percent of all the votes cast.

The thirst for powerHitler now demanded that Hindenburg name him chancellor of Germany and that he be given power to govern by decree, which would be the equivalent of a dictatorial mandate, in order to fulfill his campaign promise to wipe out the Communist Party. If not, his armed Nazi Party militia, known as Brownshirts, might take to the streets, once again, in violent protest. Hindenburg refused, instead naming Franz von Papen, a former army officer and a member of the Prussian gentry, as the new chancellor.

By autumn 1932, Papen’s government fell on a no-confidence vote initiated by the Communist Party and supported by Hitler’s Nazi Party, precipitating another national election for the Reichstag. In the November 6, 1932 election, the Nazi Party lost more than 2 million votes and 34 seats in the Reichstag, compared with the previous election, likely due to their having joined the Communist Party in support of a wildcat strike by Berlin transport workers. The press and middle-class voters saw the temporary alliance with the Communists as a betrayal of the Nazis’ anti-Red rhetoric.

Despite the reduction in the number of Nazi candidates elected, Papen’s party was still outnumbered in the Reichstag, and Hitler remained steadfast in his refusal to form a coalition government unless he (Hitler) was named chancellor. Papen reported to President Hindenburg on November 17, 1932, that he was unable to negotiate a coalition government and must, therefore, resign.

Hindenburg accepted Papen’s resignation and subsequently met with Hitler on several occasions to try to persuade him to form a coalition government without being named chancellor. Hitler’s answer was always that he would only accept to form a coalition government if he were appointed chancellor with sweeping powers to deal with the Bolshevik threat in Germany. This, Hindenburg refused, citing the intolerance of the Nazi Party and the fact that it did not have a majority in the Reichstag; only a plurality.

However in late November 1932, Toland writes in his biography of Hitler, 39 prominent businessmen signed a petition to Hindenburg in support of his naming Hitler as chancellor of Germany because of his anti-union and pro-business stance. Among those signing the petition, says Toland, were Hjalmar Schacht, president of the Reichsbank, former chancellor Wilhelm Carl Josef Cuno, and industrialists like Alfried Krupp, Wilhelm von Siemens, Fritz Thyssen, Robert Bosch, Ernst Wörmann and Albert Vögler.

Still Hindenburg refused, instead naming General Kurt Von Schleicher, his minister of defense, as chancellor on December 2, 1932. By January 20, 1933, Schleicher, who was more of a hard-headed army man than a tactful politician by temperament, had antagonized all the parties in the Reichstag.

Hitler's mesmerizing oratoryIn the meantime, Hitler, using his mesmerizing oratorical skills, threw himself vigorously into a byelection in the district of Lippe, where his party won 39.6 percent of the popular vote, a gain of 17 percent from the poor performance of the previous November and a strong indication of his renewed popularity among the electorate.

With the government apparatus in political deadlock because of Hitler’s refusal to form a coalition government and the possibility of civil war because of middle class desperation due to rampant inflation and high unemployment, Schleicher asked Hindenburg to dissolve the Reichstag, suspend elections and give him emergency military powers to deal with the Nazi threat. Hindenburg refused the request of his chancellor, who had a reputation for secrecy and scheming. Schleicher resigned.

On January 30, 1933, with Schleicher’s credibility in tatters, Hindenburg — against his better judgment but fearing a putsch by Hitler whose Nazis had infiltrated the police force in the capital of Berlin — finally gave in and named Hitler, whom he disparagingly referred to as the “house painter” and the “Czech corporal”, the new chancellor of Germany.

Hitler, the high school dropout who had lived on the streets of Vienna admiring its architecture and painting its landscapes before enlisting as a corporal in the First World War, had morphed into the strongman of Germany, flexing his steely grip on the levers of power after 14 years in the political wilderness amid continual setbacks, accompanied by symptoms of manic depression and contemplations of suicide.

He had proven himself to be a wily political survivor, learning from previous mistakes, such as his failed attempt to have Nazi thugs overthrow the national government by force of arms in what became known as the “Beer Hall Putsch” of Munich in 1923.

Fourteen of Hitler’s Nazi stormtroopers were shot dead by police in the aborted putsch and Hitler himself was arrested, convicted of treason and incarcerated for what was supposed to be five years but ended up being eight months due to what authorities called “good behaviour”. While locked up, he began writing his two-volume autobiography and political treatise titled Mein Kampf, which translates into English as My Struggle.

'The Jewish peril'The two volumes, published in 1925 and 1926, set out Hitler’s plans, once in power, to restore German military might through war, first against France and then against the Bolsheviks in the Soviet Union. He made it clear in his book that “the Jewish peril” must be eradicated which meant removing all the Jews from Europe. He alluded to the possibility of gassing them, like vermin. He also raised the spectre of euthanasia for the weak and sick of society to make room for the strong and to keep the gene pool pure. At the time, few intellectuals paid attention to his rants and threats, believing him to be washed-up jailbird.

Now in 1933, a decade after his unsuccessful attempt to seize power through force of arms, Hitler had clawed his way to the pinnacle of political power, disguising his Nazi fist of iron in the velvet glove of a dysfunctional democracy. By the time he became chancellor, 240,000 copies of his book had been sold. By the end of the Second World War, about 10 million copies of Mein Kampf had been sold or distributed in Germany, and Hitler was the equivalent of a present-day millionaire from the royalties alone. If such a movie had come out of the fervid imagination of a Hollywood producer, no one would have believed the plot to be credible.

Liberal politicians and academics inside and outside Germany were shocked at his ascension to power. Individual members of the Catholic and Protestant clergy within Germany acted heroically in protesting Nazi policies, which included the sterilization of those with mental or physical disabilities. However, on an institutional level, church authorities did not mobilize to oppose the Nazis.

On the street, average Germans suffering economic hardships were relieved to have Hitler’s strong hand at the wheel. The bigots and the vagrants of Germany, as well as the disillusioned veterans of the First World War were ecstatic.

Hitler quashes democracyFour days after taking office, Hitler addressed high-ranking military officers at the home of General Kurt von Hammerstein. Speaking of the difficult economic problems facing Germany, Hitler is quoted by author and historian Toland as saying that unemployment and depression would continue until Germany recovered her position in the world militarily. Pacifism, Marxism and that “cancerous growth, democracy” must be eradicated, he said.

Hitler called for new federal elections on March 5, 1933. But a fire in the Reichstag on February 27, 1933, which Hitler conveniently blamed on a Communist provocateur who was later executed, was used as a pretext by his cabinet to pass the Reichstag Fire Decree as an emergency measure to allow Hitler to control threats of Communist violence. The decree suspended civil liberties set out in the Weimar Constitution, such as freedom of expression and the press, as well as the right of public assembly, free association, privacy of post and telephone. The right to habeas corpus was also suspended. It was signed into law by Hindenburg.

The Nazis used the decree to arrest Communist Party leaders and to restrict activities of their other political opponents, the Social Democrats. The resources of big business and the national government were used to help Hitler garner extensive campaign coverage throughout Germany. Nazi Brownshirts monitored the voting stations on election day to scare opponents.

Despite the massive intimidation campaign, the Nazis did not win the majority they expected in the March 5, 1933 election. Instead they won 43.9 percent of the 44.7 million votes cast, giving them 288 seats in the Reichstag, a gain of 92 seats from the election of November 1932.

Hitler circumvented his lack of a majority by convincing the Reichstag to bestow on him the legislative authority to enact laws without the participation of elected members — powers which gave him more authority than that of a kaiser (German emperor) in the past. The Centre Party, which represented the interests of the Catholic Church and came in fourth place in the March 5, 1933 election with 11.4 percent of the popular vote, supported the legislation in the misguided belief that it would convince the Nazis to back off their attacks on members of the clergy, hundreds of whom, nonetheless, ended up being arrested and sent to concentration camps. On March 23, 1933, the legislation, known as the Enabling Act, was signed into law by Hindenburg.

For the vast majority of Jews, it was a menacing and uncertain future they faced in Germany, once considered to be a cradle of European culture but now a brutal Nazi dictatorship which held a public book-burning ceremony in Berlin’s Opera Square on May 10, 1933, destroying 25,000 “un-German” books.

Between June 30 and July 2, 1934, in what is known as the Night of the Long Knives, Hitler had all his major political opponents — between 85 and several hundred both inside and outside the Nazi Party — assassinated. Among those killed was his long-time loyal, Nazi colleague Ernst Röhm, who as leader of the Brownshirts militia known as the Sturmabteilung (SA) was seen as a threat by both Hitler and leaders of the army who thought he might have leadership aspirations. For good measure, Hitler also had Schleicher, his predecessor as chancellor, killed.

When Hindenburg died in office a month later on August 2, 1934 at the age of 87, Hitler declared the presidency vacant and appointed himself as head of state, as well as retaining his dictatorial powers as chancellor. As head of state, Hitler assumed the president’s position of supreme commander of the Wehrmacht, the unified armed forces of Germany. The Gestapo (secret state police) under Heinrich Himmler attacked anybody who dared oppose or speak out against Hitler or his policies.

With promises of high-technology rearmament and a renunciation of the Versailles Treaty, Hitler had the military-industrial complex firmly in his pocket. Social reform, make-work projects, government-subsidized holidays for workers, and a new plant to manufacture an affordable peoples’ car — the Volkswagen — to navigate the newly-built, national highway system known as the Reichsautobahn won the hearts of average citizens.

He promised the German nation “arbeit und brot” (work and bread) and a return to glory. And, during the 1930s, he delivered on his promises. Hitler was idolized by many in Germany, although there were numerous unsuccessful assassination attempts between the early 1930s and 1944. But in the eyes of most Germans, Hitler enjoyed the status of a modern-day rock star; men pressed the flesh at massive rallies to shake his hand or secure his autograph, while women bussed him and fainted at his touch. For some he was akin to a deity, with school children reciting prayers for his safety.

In their book, Inside Hitler's Germany: Life Under The Third Reich [2000, The Brown Reference Group PLC], authors Matthew Hughes and Chris Mann cite a survey conducted in 1951 in the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany) — six years after the Second World War had ended — which indicates that almost half the people questioned described the years 1933 to 1939 as the best for Germany. The authors also cite a 1949 survey by the German Public Opinion Institute indicating that Germans who lived through the 1930s remembered the positive aspects of Naziism — adequate work, subsidized leisure activities for workers, sufficient nourishment and a smooth-running political apparatus.

The fact that Hitler was a dictator didn’t seem to bother most Germans. They saw him as benevolent and wise. His brutality was not on public display. And, after all, didn’t God rule by decree and wasn’t the Führer an agent of the Almighty? — a belief Hitler himself fervently promulgated. The motto of his Third Reich was Ein Volk, Ein Reich, Ein Führer — One People, One Reich, One Führer.

As for the Jews, the few who could afford to start over and manage to find a country which would accept them left. There were physical attacks on Jewish individuals in Germany throughout the 1930s, along with boycotts, vandalism and confiscation of Jewish businesses. In 1935, the Nazis codified their anti-Semitism in the Nuremberg Laws, which stripped Jews of their German citizenship and forbade them to marry "Aryans".

A June 1933 census indicated there were 500,000 Jews in Germany. The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum says that between 1933 and 1939, more than 90,000 German and Austrian Jews fled to neighboring countries, all of which other than Switzerland were themselves overrun by the Nazis after war broke out on September 1, 1939. Emigration became more difficult after the war started, and the Nazis cut it off completely in November 1941.

Just how far the Nazis would go in their quest to annihilate European Jewry was foreshadowed on the overnight of November 9-10, 1938, when Hitler’s SA stormtroopers and civilian followers launched a series of coordinated attacks against Jews and their businesses throughout Germany, Austria and the Czech Sudetenland.

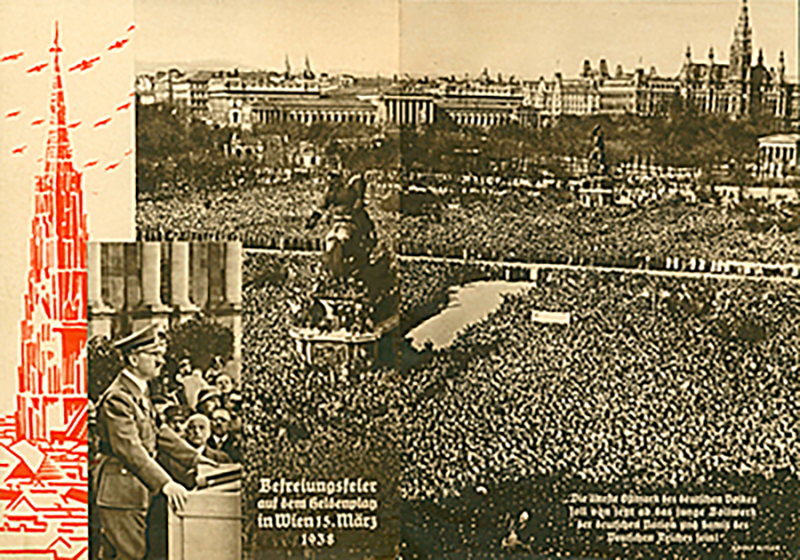

Called Kristallnacht (Night of Broken Glass), it left at least 91 Jews dead, 30,000 arrested and locked away in concentration camps, over 1,000 synagogues torched and more than 7,000 Jewish businesses destroyed or damaged. No government reacted to stop Hitler, just as it had not blocked him from annexing both Austria in March 1938 and the ethnically German Sudetenland part of Czechoslovakia in October of the same year, as part of the Munich Agreement signed by British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain in an act of appeasement seeking “peace for our time.”

The Munich Agreement and Kristallnacht made it clear to Hitler that he had de facto carte blanche from the rest of the world to impose his “Final Solution” on European Jewry while redrawing the map of the world through conquest of arms imposed by a robust German military machine. The armed forces went from 100,000 men when Hitler took power in 1933, to almost 4 million men just before war broke out in 1939, to about 16 million conscripts during the war itself.

Some Christians rally for the JewsIn the rest of Europe, Jews such as Alt had no way of knowing how far-reaching and efficient would be the purview of the horrific Nazi death machine with its concentration camps designed for mass slaughter. Few spoke out to save the Jews although some tried surreptitiously to help them escape.

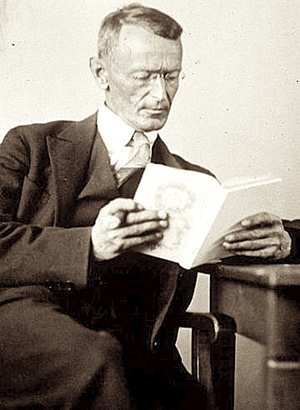

Decades before the slaughter began, certain German intellectuals such as author Hermann Hesse wrote about the dangers of German nationalism, both in newspaper articles and in his books, like Steppenwolf published in 1927 and translated into English two years later.

Hesse, who left Germany and acquired Swiss citizenship in 1923, wrote an essay in 1914 at the beginning of the First World War called O Friends, Not These Tones, in which he appealed to German intellectuals to reject nationalism. He later said that such writings exposed him to hate mail, attack in the German press and isolation from old friends.

In his novel Steppenwolfe, written in the Expressionist literary style which conveys the innermost, troubling thoughts of the protagonist, Hesse delves into the isolation of a middle-aged artist named Harry Haller whose idealism and humanism leave him feeling estranged from the barbaric aspects of modern, technological society with its bourgeois values based on materialism and exploitation.

In an example of art imitating life, Haller, the main character in the novel, confides to a female companion about the way the press has attacked him for speaking out against Germany gearing up for new battles to avenge its defeat in the First World War:

Now and again I have expressed the opinion that every nation, and even every person, would do better instead of rocking himself to sleep with political catchwords about war guilt, to ask himself how far his own faults and negligences and evil tendencies are guilty of the war and all the other wrongs of the world, and that therein lies the only possible means of avoiding the next war. They don’t forgive me that, for, of course, they are themselves all guiltless, the Kaiser, the generals, the trade magnates, the politicians, the papers….Not one has any guilt….One might believe that everything was for the best, even though a few million men lie under the ground….Nobody wants to avoid the next war, nobody wants to spare himself and his children the next holocaust if this be the cost….

And so there’s no stopping it, and the next war is being pushed on with enthusiasm by thousands upon thousands day by day. It has paralysed me since I knew it and brought me to despair. I have no country and no ideals left. All that comes to nothing but decorations for the gentlemen by whom the next slaughter is ushered in.4

Hesse, who wrote Steppenwolfe in 1927 when he was 50, remarried for the third time shortly thereafter, this time to an art historian and Jewish woman 18 years his junior named Ninon Dolbin Ausländer. From his base in Switzerland in the early 1930s, Hesse continued to protest Nazi ideology by speaking publicly in support of Jewish and other artists persecuted by Hitler’s henchmen.

Hesse won a Nobel Prize in Literature in 1946 for the futuristic novel The Glass Bead Game, which took him 11 years to complete. He said working on the novel was his spiritual refuge from the Second World War. He sent the manuscript to Berlin to be published in 1942, but it was rejected by the Nazis. Instead, it ended up being published in Zürich in 1943.

The conditions for genocideAll the political machinations within Germany with their dire implications leading up to Hitler consolidating power in the winter of 1933 would have gone unnoticed by a then-10-year-old boy named Duddy Alt living a care-free, upper middle-class life in neighbouring Hungary.

When asked to what he attributes his survival, Alt replies in the hushed monotone of a survivor who has become inured to horror: “I don’t think I have a mission in life. I don’t think that I’m special. It just happened.”

When Alt says “it just happened”, he is referring to his survival. But looking at the larger question as to why so many genocides occurred in the 20th century, one is struck by the juxtaposition between science and humanity. For all the wondrous, life-saving discoveries in medicine and advances in technology, there has been no corresponding shift towards creating a more benevolent, egalitarian world.

The list of ignominious massacres rolls off the tongue, starting with the Armenian Genocide of the First World War; the Jewish Holocaust of the Second World War; the Indo-Pakistani War of 1947, which included massive riots and atrocities in the disputed Punjab region; the Bosnian War of the early 1990s, with its Siege of Sarajevo from April 1992 through February 1996; the Rwandan Genocide of 1994; and the Darfur atrocities in Sudan, which began in 2003 and continued into 2012. Along the way, there have been other incidents of “ethnic cleansing” in Asia and Africa. Governments have also used deadly force to subdue their own civilian protesters demonstrating for human rights, such as occurred in Tiananmen Square in China in 1989, in Iran in 2009, in Bahrain in 2011 and in Syria starting in 2011 and continuing into 2012.

It’s apparent that massacres don’t “just happen.” One can conclude that, on the balance of probabilities, ethnic violence will occur when a disproportionate amount of political and economic power rests in the hands of an oligarchy seeking to deflect attention from corrupt governance.

The only antidote to such state terror is a vigorous democracy with human rights and freedoms constitutionally enshrined to protect the most vulnerable. Diverse, unfettered news media are a crucial component in safeguarding constitutional democracies whose governments are mandated to serve the best interests of all their citizens.

One of the lessons learned from Nazi Germany is that any society’s freedom is only as strong as the rights enjoyed by its minorities. Martin Niemöller, a German Protestant pastor, organized opposition and spoke out publically against Hitler’s policies, which led to his arrest in 1937 and to his imprisonment in a concentration camp between 1941 and 1945. Niemöller is acknowledged as the author of a famous statement about the importance of speaking out on human rights abuses based on his experience with the Nazis. There are several variants of his statement which have been published, but American Protestant clergyman and scholar Franklin Hamlin Littell, who met with Niemöller after the war, emphatically stated that what follows is the correct version:

First they came for the Communists, and I did not speak out because I was not a Communist.

Then they came for the socialists, and I did not speak out because I was not a socialist.

Then they came for the trade unionists, and I did not speak out because I was not a trade unionist.

Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak out because I was not a Jew.

Then they came for me, and there was no one left to speak out.

Perhaps Alt’s mission as a survivor is to remind all of us — at a minimum — to “speak out”, to confront on an intellectual basis intolerance and corruption wherever and whenever we encounter it.

One such courageous man who has spoken out against the evil of anti-Semitism is Canadian journalist Tarek Fatah, who is the founder of the Muslim Canadian Congress, a liberal group which several years ago successfully opposed the introduction of Sharia law in the family court system of Ontario.

Fatah has written a book titled The Jew Is Not My Enemy, published in Toronto in 2010 by McClelland & Stewart (ISBN 978-0-7710-4784-8). In it, he tackles head-on the myths which fuel Muslim anti-Semitism.

Fatah is an Indian born in 1949 in Pakistan whose Hindu ancestors in the Punjab converted to Islam in the 19th century. In his book, he writes: “My heritage was deeply interwoven with that of the Sikh religion and Hinduism’s ancient wisdom. The Islam of Punjab had no room for hate. The three faith communities were woven together by a common culture, cuisine and clothing, and by a humour that could defuse the most intense altercation. Yet in 1947 — Muslims, Hindus and Sikhs — we managed to break a thousand-year-old relationship in a frenzy of bloodletting that killed a million people in a matter of six short months. How then could I, a child of a maniacal religious massacre, afford to hate the ‘other’ ?”

Fatah says Pakistan had no tradition of anti-Semitism in the late 1940s and 50s when he was a young boy growing up there, but when he returned in 2006 for a visit, after an absence of 17 years, he was shocked by what he calls “the ubiquitous hostility towards the Jewish people.”

It was during his 2006 visit that he decided he must write a book “to right the wrong” of Muslim anti-Semitism. The correctness of his decision was confirmed in 2010 when he heard a speech given by Tun Mahathir bin Mohamad, who was prime minister of Malaysia between 1981 and 2003 and was, in Fatah’s words “one of the towering political leaders of the Muslim world.”

The speech, as reported in the Jakarta Globe of January 21, 2010, quoted Mahathir as saying that Jews “had always been a problem in European countries. They had to be confined to ghettos and periodically massacred. But still they remained, they thrived and they held whole governments to ransom….Even after their massacre by the Nazis of Germany, they survived to continue to be a source of even greater problems for the world.”

Fatah concludes that the former prime minister of Malaysia is just one of over 1 billion Muslims worldwide who “are constantly being told by clerics about the essential deviousness of the Jew and the global conspiracies he weaves.”

And for those who think that Muslim enmity towards the Jews would cease if Israel gave up all the land on the West Bank and even if it relinquished Israel proper as a Jewish state, here is a translation from Arabic into English of what Egyptian cleric Muhammad Hussein Yaqub said on Al-Rahma Television on January 17, 2009, as reported by Fatah in his book:

If the Jews left Palestine to us, would we start loving them? Of course not. We will never love them. Absolutely not…They are enemies not because they occupied Palestine. They would have been enemies even if they did not occupy a thing….You must believe that we will fight, defeat and annihilate them until not a single Jew remains on the face of the earth….As for you Jews, the curse of Allah upon you. The curse of Allah upon you, whose ancestors were apes and pigs. You Jews have sown hatred in our hearts and we have bequeathed it to our children and grandchildren. You will not survive as long as a single one of us remains.

So instead of allowing history to grow dim with time, let us retell the survival story of men like Duddy Alt and then join with moral leaders like journalist Tarek Fatah and younger generations of concerned humanitarians who refuse to turn a blind eye to such evil.

1"The New Jewish Encyclopedia", published by Behrman House Inc. in New York in 1962, cites a population of 650,000 Jews in Hungary before the Second World War, whereas a current online search through the U.S. Library of Congress cites 725,000 Jews living within Hungary’s expanded borders of 1941. The discrepancy is likely due to the shifting boundaries of European countries prior to and during the Second World War.

2Again there is a discrepancy in figures: "The Junior Jewish Encyclopedia", published by Shengold Publishers Inc. of New York in 1963, cites 120,000 Hungarian Jews who survived the Second World War, whereas a current online search through the U.S. Library of Congress cites 260,500 Jews living in Hungary’s expanded borders of 1941 who survived the war. As in the previous footnote, the discrepancy is likely due to the shifting boundaries of European countries prior to and during the Second World War.

3John Toland. "Adolf Hitler". New York: Anchor Books. Toronto: Random House of Canada Ltd., 1992. ISBN 0-385-42053-6; p. 261

4Hermann Hesse. "Steppenwolfe". New York: Bantam Books in conjunction with Holt, Rinehart and Winston Inc., 1974. Originally translated by Basil Creighton in 1929 and updated by Joseph Mileck and Horst Frenz in 1969; pp. 133-134