Updated: date

Published: October 28, 2019

The boy who eluded the Nazi death machine and grew into America’s obscure Renaissance man

By STAN CROCK

Writing from Washington, D.C.

One day in 1935, a Jewish art dealer in Berlin, Germany named Eugen Peisak thought a Nazi Party member had hurled an insult at him in a restaurant. Peisak slugged him. Then Peisak found out the Gestapo was after him. He bolted to Sweden.

He left behind his wife, Elizabeth, and 6-year-old son, Claus. Elizabeth realized she and Claus had to flee too. After sweet-talking an officer at the local police station into providing a tourist visa for France, mother and son stole away that night for Paris. After two days, they moved to Zurich, where her ailing father, Leopold Abt, lived. She put her son in an orphanage and promised to return soon.

A couple of days stretched into a couple of weeks, and Claus became depressed, despairing that his mother would ever return. When she finally did, he refused at first to talk to her, but they finally reconciled. From the orphanage, Claus went to stay with his grandfather for a couple of months and eventually attended first grade at a boarding school in St. Gallen in eastern Switzerland. He stayed for a year. His mother visited once, at Christmas.

The next move for Elizabeth was a tourist visa for London, where she had studied Shakespeare after World War I. Her timing was less than impeccable. She went to the U.S. Embassy to apply for a visa at a time when Washington was allowing in only a quarter of the immigration quota for Germany, effectively excluding thousands of Jews facing growing repression in Germany. The embassy flatly rejected her request on the ground that she was in England on a tourist visa. She would have to return to Germany to apply. Her argument that the Germans would send her to a concentration camp fell on deaf ears.

The next day, though, her fortunes changed. Dramatically. The embassy phoned. “When may a limousine call for you, madam?” an embassy staffer inquired solicitously. The reason: her connections were more than impeccable. After the embassy rejection, Elizabeth returned to the bed-and-breakfast where she was staying and phoned a cousin Claus called “Uncle Julius”. That would be Julius Ochs Adler, the general manager of The New York Times. He had visited Elizabeth’s family in 1915, before the U.S. entered World War I, when he was a young Army captain. He had offered to take Elizabeth to New York for safekeeping during the war, but her father demurred. A supporter of German Kaiser Wilhelm II, he said that wouldn’t be necessary because Germany would win the war.

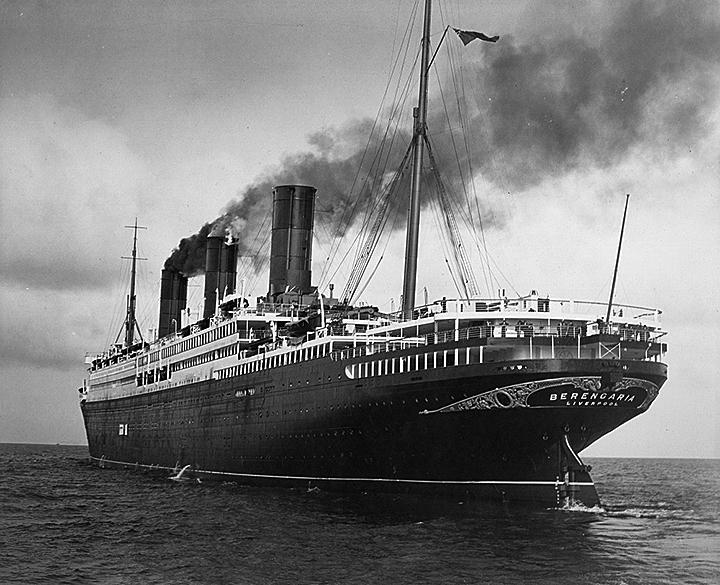

After Elizabeth’s call, Adler phoned President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR). The White House then called the embassy and ordered it to issue the visa. When she arrived at the embassy, the ambassador, Robert Worth Bingham, asked whether she was the lady who was the subject of the phone call, then grumpily stamped her passport. She fetched Claus in St. Gallen, and they sailed for the U.S. aboard the Cunard-White Star liner Berengaria. They occupied a second-class cabin, and the steward brought breakfast in bed. Claus tasted orange juice for the first time.

Correction: The original version of our story posted on October 28, 2019 incorrectly stated that Joseph P. Kennedy was the U.S. ambassador to the U.K. when Elizabeth Abt applied for a visa to immigrate to America. In fact, Kennedy took over as ambassador in 1938, months after Elizabeth and Claus arrived in the U.S. A sharp-eyed reader discovered the mistake after uncovering documentation indicating that Elizabeth and Claus arrived in New York City in April 1937. Clark Abt subsequently passed word to the author, Stan Crock, that his mother referred to “the ambassador”, but not by name, and as a young boy at that time, he had assumed it was the high-profile Kennedy. BestStory.ca corrected the story on November 12, 2019, one day after Mr. Abt confirmed the error.

Story of a Renaissance man

So begins the tale of one of the most remarkable and influential people most folks have never heard of. Today Claus Peisak is Clark C. Abt. From the transatlantic crossing, his journey included attending school in New York City, graduating from Massachusetts Institute of Technology, a hitch in the Air Force as a navigator, electronic countermeasure specialist and intelligence specialist, and working as an engineer and manager in Raytheon Co.’s missile division. All of this prepared him for his ultimate achievement: the founding in 1965 of Abt Associates in a modest, two-room office above a machine shop a couple of miles from Harvard Square in Cambridge, MA. Abt Associates now is a major player in policy research and international health and development, activities aimed at helping the most vulnerable people in the U.S. and abroad.

In his nine decades on the planet, Abt’s breadth of interest and activities has rivaled that of Leonardo da Vinci, as the enclosed table shows. He has been an entrepreneur, engineer, rocket scientist, social scientist, environmentalist, educator, game theorist, social-accountability guru, poet, architect, literary magazine editor, artist, and more. “He’s obviously very smart and very eclectic,” says Chris Hamilton, a poverty expert and former Abt Associates vice president who worked for the firm from 1966 to 2003. “He always thought of himself as a Renaissance type.”

Abt dismisses the comparison, saying da Vinci had far more impact. And Hamilton notes that it was hard in the 20th century to be the kind of Renaissance man Abt aspired to be simply because there was so much knowledge to master in a given field, compared with the 1400s. “Da Vinci had it easy”, Hamilton argues.

However intriguing Abt’s artwork is, many of his scores of paintings are in his basement, not the Louvre. None has sold for $450 million, as did da Vinci’s “Salvator Mundi”, one of only 16 pieces he finished. Yet Abt’s influence has been both significant and broad, if more subtle and under the radar than da Vinci’s. “Most people who are Renaissance men are much more into the thinking part and much less into the doing part,” notes David Ellwood, a former Abt Associates board member and former dean of Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government. “Da Vinci hardly ever finished anything.” In contrast, he added, Abt “tried to do things.” Abt’s genius, says former Abt employee Ray Glazier, is that he “sees the ramifications of new ideas.”

Interviews with Abt, his family and former colleagues and a review of his unpublished reflections on Abt Associates’ first 20 years provide details about his role as a major player behind the scenes in America’s national security strategy and socio-economic policy. The company he founded relied on the systems analysis techniques he had honed in the military and defense industry in the 1950s and 1960s. Some people bring rocket science to stock trading. He brought it to solving social ills.

And he was everywhere – nothing less than an intellectual Zelig, with an uncanny knack for being in important places with important people doing important work at important times:

- While in the Air Force, he worked on the first computerized simulation of a Soviet attack on Europe that led to a nuclear exchange.

- He also developed a way to set target priorities from all the target data tactical aircraft receive and was awarded the Air Force Commendation Medal for his work.

- At Raytheon, he oversaw the analysis of how in 1960 the Soviets shot down a high-flying, American U-2 spy plane, a major international incident at the height of the Cold War.

- His strategic analysis while at Raytheon helped maintain the balance of power in the Middle East in the 1960s through arms sales that actually promoted strategic stability.

- At Abt Associates, he helped launch the social policy research field to document the impact of the 1960s War on Poverty, from federal government housing policies to early childhood programs.

- Following the collapse of the Soviet Union in December 1991, he worked with government contacts to collaborate with Russian nuclear scientists to get them commercial work so they wouldn’t sell their weapons skills to a malevolent high bidder.

The divorce

It was hardly clear from Abt’s difficult early years that he would rise to be such a formidable figure. He was born in 1929 in Cologne to parents from quite different economic strata. His father came from an East Prussian working-class peasant family. An army infantryman, he was awarded the Iron Cross Second Class in World War I after suffering a serious shrapnel wound in a bombardment.

Elizabeth Abt was the bright, beautiful and bold daughter of a Munich millionaire who supplied all the grain to Bavaria during World War I and moved about Munich in a chauffeur-driven, four-door Mercedes sedan. He achieved the rank of commercial counselor, the second highest civilian rank in Germany. Eventually the Nazis plundered his wealth, and he was reduced to living in a pensione in Zurich by the time Abt stayed with him. One of the grandfather’s rare sources of solace in Zurich: cheering for Jesse Owens’s victories in the 1936 Olympics.

Judaism seemed to be one of the few things Claus’s parents had in common. And it was something that would play a recurring role in his life. By the time his father threw his life-altering punch at a Nazi in 1935, his son had already been expelled from kindergarten because of his religion. That confused Claus. He couldn’t understand what he had done to merit the dismissal. Sitting by his swimming pool and waterfall recently in the backyard of his tasteful Cambridge home, he recalls that his mother simply told him that the school “didn’t want people like us.”

Not long after he got to New York in 1937, he faced another educational setback. He was held back for a half year in third grade because he was ill-prepared. That made him determined to work harder. So did his “bad ass single mother”, says Abt’s daughter, Emily.

School wasn’t the only source of angst for Claus. Iphigene Sulzberger, wife of the Times’ publisher, had helped Claus’s father get to the States, and the Ochs-Sulzberger clan had interceded to get him a job at Parke-Bernet Galleries, the nation’s leading fine art auction house. One day someone asked Eugen to help move some furniture, and he replied, “I don’t move furniture.” He was fired on the spot. An argument then erupted in the family’s tiny apartment on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. Abt’s mother, Elizabeth, was livid because her husband had humiliated her family, which had gone to bat for him. And he was jobless. Eugen told her that she and the child could jump in the Hudson River.

She quickly hired a divorce lawyer, who informed her adultery was the only ground for divorce in New York State. Neither parent wanted that, so the resourceful Elizabeth flew to Reno, NV, got a divorce there, and changed her name – and her son’s – back to her maiden name. At the time, divorce was considered disgraceful among educated middle-class families – another setback for Claus.

Elizabeth, who had never worked before, adjusted quickly to her role as a working single mom. Her first job was as a masseuse in a Helena Rubenstein salon. Rubenstein took one look at Elizabeth’s stunning complexion and said: “All you have to do is say you use my cosmetics.” Elizabeth later became a saleslady and, eventually, an insurance broker.

A nasty custody fight ensued after the divorce. When Abt’s father wanted visitation rights, his mother took him to court. He could have visitation rights, the judge said, if he paid child support. Looking gray and ill in court, Eugen turned his empty pockets inside out, saying he had no money. At the time, he was living with his older brothers and sisters, whom Elizabeth considered low-lifes.

The judge put 8-year-old Claus on the stand and asked him if he loved his father. With his mother and her lawyer glowering at him, he answered, “No.” The rather judgmental judge replied, “You’re a strange child.” Claus recalls that at the time, he didn’t love his father. His mother won the court fight, and the hearing was the last time Claus saw his father. (His mother’s lawyer, who had won her trust during the divorce proceedings, subsequently defrauded her and other clients of thousands of dollars in an investment scheme.)

In the late 1940s, Claus’s father passed away from cirrhosis of the liver. Years later, Abt felt guilty that as a child he had rejected him. He wrote a poignant poem about his father titled, “Provider”, which appeared in Audience, A Quarterly Journal of Literature and the Arts, a magazine he edited. The point of the poem: his father wasn’t much of one.

An education on war

While the time he spent with his father was relatively short, the effect on the arc of Claus’s life was profound. When he was about 7, his father was drying himself after a shower, and Claus asked him about the deep scars on his upper back. They were from shrapnel, his father explained, but his World War I story was more complicated than that.

His father said that he had taken shelter in a muddy shell crater after a bombardment when an enemy French soldier jumped into the same crater. They raised their rifles at each other. But explosions overhead forced them to try to protect their faces. They lowered their rifles and glared at each other. The French soldier shrugged and put down his rifle. Claus’s father did the same. They nodded to each other, acknowledging their common misery. When the bombardment ended, and it was safe to leave the crater, the Frenchman picked up his rifle, kept it lowered, waved to Claus’s father, and climbed out to head to his front line. Claus’s father did the same and said he wished many others had.

“This was my first vicarious experience of the horrors of war and blessings of peace,” Abt wrote years later. “I’ve never forgotten it, always wondering if I had the courage to fight and to stop fighting if I had to.” The conversation with his father launched Abt’s lifelong fascination with war – and with ending war.

Uncle Julius wasn’t Abt’s only “uncle”. In fact, not his only uncle associated with the Times. Another was Uncle Birchie – Frederick Birchall, the chain-smoking Times Berlin bureau chief who had helped the family escape Germany. A Pulitzer Prize winner for his interviews with and coverage of Hitler, Birchall also had interviewed political leaders Neville Chamberlain, Winston Churchill and Mahatma Gandhi. A Brit and a hard-headed realist, he saw World War II coming, predicted appeasement would fail, and recognized the imperative of U.S. intervention to defeat the Nazis.

Birchall had moved to New York to oversee the Times European news coverage and was a frequent guest at the Abt’s new home at 19 East 95th St. Abt viewed him as a foster grandfather. Birchall showed up because of his interest in Abt’s mother — he wanted to marry her – but he was attentive to Abt.

While Abt’s mother cooked in the kitchen, Birchall gave him “a ringside inside view of the international politics of war and peace all through World War II and its triumphs and tragedies, its successes and failures, its military and political problems, solutions and errors on both sides,” Abt wrote.

This dovetailed with Abt’s precocious interest in war and peace since his father’s story about the Frenchman in the crater. The discussions bolstered Abt’s interest in military aviation, naval technology and Abt’s dream of becoming a fighter pilot and aeronautical engineer. Birchall also taught Abt that “investigating, researching and writing about important issues was a noble pursuit that could make a difference to the outcome of major conflicts,” Abt wrote.

The goateed Birchall accompanied Abt’s mother to her son’s eighth grade graduation, and a number of people commented on what a distinguished dad he had. Abt didn’t correct them.

Abt duplicated his Birchall experience with his children. When they were young, he had them read the front pages of the Times and Boston Globe every day and discuss the stories. “He would engage us as if we were serious intellectuals,” his son, Thomas, recalls, because his parents thought being a responsible citizen was important.

As unusual as his education at home was for a boy his age, Abt was in many ways a normal 8-year-old. His most important goal was to be an All-American Boy. And that meant changing his first name, Claus. That would avoid the frequent “Claus the louse” barbs of his peers – and perhaps some of the anti-Semitism Emily says he endured. Abt’s mother agreed with her son’s first-name change as long as he retained the first two letters. His mother liked Clark Gable, and Claus liked Clark Kent. So the decision on a new name, Clark, was not hard. Claus became his middle name.

The young entrepreneur

When he was 10, Abt continued to indulge in his fascination for all things military – and demonstrated his determination, ingenuity, and entrepreneurial bent. He and his best friend, Artie LaCov, played naval battle games regularly, using tin battleships, cruisers and destroyers that Artie’s wealthy mother had bought at FAO Schwartz. Artie grabbed all the $5 six-inch-long battleships with half-inch, three–gun turrets that simulated powerful 14-inch guns. That left Abt with the cruisers and destroyers, which had less firepower and put him at a decided disadvantage.

He couldn’t afford to buy battleships with the 25 cents an hour he earned delivering butcher packages on weekends, so he improvised. He bought softwood, gray paint, airplane glue, and X-Acto knives to build his own fleet. Uncle Birchie, who by then was heading British War Relief, provided accurate plans of Royal Navy ships.

While Abt managed to make the battleships, he couldn’t afford enough of them to compete with Artie – his first encounter with the effect of cost overruns. He tried to sell his existing battleships to FAO Schwartz to get more money to buy raw materials to build a larger fleet from scratch, rather than buying more expensive pre-made models. When FAO Schwartz rejected them, Abt asked the store’s buyer who else might be interested. The response: Saks Fifth Avenue.

Saks bit. He was thrilled with the $10 he received – until he saw the display with a $20 price tag. When he tried to negotiate a higher payment for the next batch, the Saks’ buyer wasn’t interested. She told him Saks was discontinuing the hard-to-sell product. Did he want $10 or not? He took the money with gritted teeth, knowing he had enough to match or beat Artie’s fleet, and he closed his “business”.

A New York education

As he moved through the New York school system, several teachers broadened the understanding and interests of this eager sponge of a student. His sixth-grade English teacher, a Mrs. McBarron, paraded back and forth in front of the class, warning students that the Federal Bureau of Investigation, college admissions offices and corporate personnel managers would come back to the school to investigate them and make decisions based on her evaluation of their behavior. The kids thought she might be exaggerating, but they were never sure enough to dismiss the message completely. Her threats impressed on Abt that there could be future consequences of every action he took.

Abt was a good enough student to gain acceptance to the prestigious Brooklyn Technical High School, which provided a crucial formative experience. It was one that went far beyond the math, science and technology for which the school was famous. As he listened to FDR’s fireside chats with his mother at home, his studies confirmed for him that the American government was the best in history.

But the school also gave him a complex and nuanced view of the country that had rescued him. This was, after all, New York City, whose political spectrum spanned all the way from Communists on the left to progressives on the right. Abt’s teachers gave students a healthy dose of skepticism about America, pointing out its warts: oppression of slaves, cruel exploitation of immigrants, union suppression, and denial of equal rights to women and minorities. As a refugee from the Nazis, he sympathized with the social reform movements he learned about. He began to read the works of British philosopher Bertrand Russell and became interested in the potential for social change.

Abt’s mind and interests scattered in many other directions as well. In his foundry class, he designed a heated air-pressure-actuated foundry temperature gauge that he wanted to patent. He tried his hand with little success as a Golden Gloves boxer. And he served as editor of the school’s science bulletin, perhaps a prelude to his tenure as editor of a literary magazine. When he was a sophomore, he wrote an article for the bulletin about supersonic flight, a novel development; Birchall arranged for him to become a young student member of the Institute of Aeronautical Sciences library. The following year, after William L. Laurance of the Times wrote about the atomic bomb, Birchall arranged for Abt to interview him about nuclear weapons.

During Abt’s senior year, he won a New York State Regents Scholarship, which he could use at any college in the state. But which school? During World War II, he had wanted to be a fighter pilot, and after the war, he wanted to be a test pilot like Clark Gable and Spencer Tracy in the movie, Test Pilot. Abt’s nearsightedness – ironic for someone so farsighted intellectually – made him ineligible to be a pilot and scotched those dreams. So he hit on becoming an aircraft designer, like Leslie Howard in The First of the Few, a movie about the designer of the Spitfire, which helped win the Battle of Britain.

Abt’s mother went along with his desires and suggested fine engineering schools in New York State such as Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute and Cornell, to make use of the scholarship. But Abt wanted the best aeronautical engineering program, and that meant Massachusetts Institute of Technology. The $1,400 Regents Scholarship went up in smoke, and his mother never forgave him. To compensate for the loss of money, Abt worked as a proof-press printer at the Times after graduating from high school six months early.

Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT)

While Abt was certain about aeronautical engineering when he started, he ended up switching among five majors. Aeronautical engineering got too mathematical for him. He took the Kuder Preference Record testing at Harvard’s Psychology Guidance Center, which showed he had a talent for drawing and visualization. So he switched to architecture. Then he learned the architecture degree took five years. He didn’t have the money for that. So he switched again, this time to mechanical engineering (stifling his aspiration to write the next great American novel). Next was industrial engineering, and finally he ended up with a general engineering degree.

He had failed so many courses, though, he did not seem headed for graduation. Then a professor suggested he write a novel as his senior thesis. The novel about an unhappy undergrad love affair was the first by an MIT undergraduate for thesis credit and enabled him to get his degree. When his thermodynamics professor handed him his diploma on stage – like half the class, Abt had flunked thermodynamics the first time – the professor looked at him quizzically. “Jesus Abt,” he said, “I never thought I’d see you here.”

The ever-evolving Abt

Abt changed his religious beliefs and his politics almost as many times as he switched majors. Birchall was a Unitarian, and his influence led Abt to switch to that faith from Judaism. It was not a hard push. Abt had attended a boarding school briefly in New Jersey and liked the hymns and Bible lessons. “They treated me like everyone else,” he recalls.

When he returned to school in Manhattan, his mother enrolled him in a synagogue-affiliated religious school. It was not the best fit. When he asked why there was no discussion of Jesus, as there was everywhere else, the teacher was not amused. It didn’t help that when Abt went to a Jewish summer camp, one of the taunts he heard too often was: What kind of cheese comes from Germany? Refucheese. Abt’s first marriage was in a Unitarian church.

Abt’s second wife, Wendy Peter, came from a mostly Irish Catholic family, but three of four sisters married Jewish men and two converted to Judaism. His daughter, Emily, belongs to a reform Jewish synagogue and is raising her daughters Jewish. Now, Abt says, “I remain Jewish by blood, Unitarian Protestant by secular preference, and atheist scientific humanist by faith and conviction” (as is Wendy). Abt may have left the religion of his birth, but between his daughter and in-laws, he didn’t escape very far.

His politics evolved similarly. Abt supported Democrat FDR enthusiastically. “He had saved our lives,” Abt says. He also supported Republican President Dwight Eisenhower because when Abt was in the Air Force and deployed to Europe, he saw first-hand the Soviet threat. He recalled hearing the broadcast when Russian tanks rolled into Hungary in 1956, “and we couldn’t do a damn thing about it.” From liberal Republican, he switched to independent, and then to moderate/liberal Democrat. He was a supporter of Democrat John F. Kennedy.

Abt evolved professionally, too. After getting his engineering degree, he didn’t follow a standard engineer’s path. He spent four months in the Merchant Marine as an ordinary seaman. Then he taught freshman English at John Hopkins University for a year while studying writing, literature, poetry and philosophy and earning a master’s degree from the Department of Writing, Speech and Drama. His thesis: “A Year of Poems”.

From 1952 to 1953, his day job was working for Bechtel Corp. in San Francisco as a power plant engineer. At night, he prowled the Vesuvio Cafe and City Light Bookstore, mingling with second-tier beat poets. “I tried to write beat poetry,” Abt recalls. “I was not very good.”

The Korea conundrum

As the Korean War heated up in the early 50s, Abt wanted to quit his job at Bechtel to become a writer because he thought he could help his country more that way than by being an engineer. His mother was beside herself and asked Uncle Julius, by then a retired major-general, to intervene. Abt went to meet with him, and Adler asked what all the nonsense was about dropping engineering to become a writer. When Abt explained his reasoning, Adler quickly dismissed him. “That was painful and a little scary,” Abt recalls.

The war posed a dilemma for him. As the risk of getting drafted into the Army grew, liberal friends and the beat poets recommended that he evade the draft by fleeing to Canada. But Abt felt indebted to the country that had rescued him and wanted to serve. “My pacifist friends were disgusted with me,” he says.

But he didn’t want to join the Army. He had no interest in shooting anyone or being shot at, at least not at close range. Nor did he want to sleep in the cold mud, much less die an agonizing and slow death in the muck with a bayonet or bullet in his belly. And he wanted to command, not be under the thumb of a bullying sergeant. He also knew more about planes and boats than infantry, so the Army was out.

What about the Navy? Then-Senator John F. Kennedy’s tales of his PT-109 exploits were intriguing, romantic – and alluring for Abt. Unfortunately, he learned when he applied for a direct commission that naturalized citizens weren’t eligible for one. (He had been naturalized in 1945.)

That left the Air Force, where combat took place at a comfortable and sanitary distance. “It was clean beds and a warm cockpit for me until my time came,” he wrote. With a pilot’s role out of the question, he hoped to launch aloft as a navigator. His timing couldn’t have been better. The Air Force was recruiting for a direct commission program that combined navigator training and electronic countermeasures – an ideal marriage for an MIT-trained engineer.

Within two years, he got to command, too, as the chief of a two-man, anti-aircraft battle branch of the 12th Air Force operational intelligence. He considered air defense noble. You killed only threatening aggressors.

But he was ambitious and looked for even more challenging tasks. He got his chance in June, 1954. A big NATO operation was simulating a sudden Soviet invasion of Western Europe: the NATO, U.S. Air Force, and Royal Air Force’s response involved – for the first time – using simulated nuclear weapons. Abt served as liaison with the U.S. and NATO European Air Force Headquarters in “The Cave”, a supersecret command center in caves under the World War II Maginot Line. There they followed and plotted the progress of “Carte Blanche”, the first simulated NATO-Soviet nuclear war.

Abt’s task: read telexes, answer phoned-in situation reports and drink 20 cups of coffee a day to stay up for four days straight. He used colored grease pencils to mark nuclear strikes on plastic overlays of a map of Western Europe. At the end of the four days, most of the plastic was covered with red circles for nuclear detonations and larger yellow cigar-shaped lethal fallout contours. “Apparently we would have to destroy Germany and its population to save it from the Russians,” he mused.

Participation in this ground-breaking exercise led to an epiphany for the young engineer and strategist. He had the sense for the first time that a monstrous nuclear war actually could occur as the result of a small miscalculation. And he concluded that he might be able to make a valuable contribution. With thought, analysis and planning, he could help avert the madness. The generals and strategists weren’t so smart, after all, if they could in theory kill millions in a few days and produce a defeat for everyone instead of a decisive victory. To help defend the West and avoid nuclear war, Abt decided to dive deeply into war planning, operations analysis, and command decision-making as soon as he could – but not before visiting as many European and North African capitals as he could to see their cathedrals, art galleries and museums.

The Raytheon years

When his Air Force stint ended in 1957, he joined Raytheon Co. It offered high-tech work and Boston’s attractive cultural environment. The Hawk surface-to-air missile system and the Sparrow air-to-air missile both were moving from development to testing, so Abt could witness the most advanced military, scientific and technological developments in the world. His task was to determine where to place Hawk missile batteries and to figure out operational tactics that would shoot down the largest number of incoming Soviet bombers.

He moved up steadily for seven years, holding engineering and management positions, including managing the Advanced Systems and Strategic Studies departments in the company's Missile and Space Division. As a sideline, from 1958 to 1960, he was editor-in-chief of the literary journal Audience and worked 90-hour weeks to do both jobs.

His interest in strategy led him to join the Harvard-MIT Arms Control Seminar taught by Henry Kissinger and Thomas Schelling, two of the foremost nuclear strategists. Though he was the youngest participant, Abt played a critical role because he was the only one who knew whether the strategic theories meshed with the realities of available missile technology. And he had been doing more and more strategic policy work at Raytheon.

The seminar, in turn, prompted him to apply for MIT’s PhD program in political science. But it wasn’t the only reason. He felt he had topped out at Raytheon, whose focus was on equipment sales, not strategy. To expand his role in the strategy world, he would need the skill and credential a PhD could bring. So from 1961 through 1964, he worked three-quarter time at Raytheon while earning his PhD. He called his dissertation, an analysis of the end of the two world wars, “The Termination of General War”.

The years at Raytheon were eventful. In 1960, Abt found himself in the middle of one of the most dramatic events of the Cold War. On May 1, 1960, the Soviets shot down a CIA U-2 spy plane deep in their territory and captured the pilot, Gary Powers. The incident shocked the Pentagon, which didn’t think the Soviets had the capability to shoot down a plane flying at 70,000 feet.

Earlier in the year, Abt had helped Raytheon win a contract to create a Quick Response Capability Technical Intelligence Center. Its task now was to figure out how Moscow did it. The Soviets’ self-importance and unthinking bureaucracy helped. Fortunately, Moscow mechanically held its May Day parade without considering how the display of the SA-2 high-altitude, surface-to-air missile was an intelligence bonanza for the U.S. An American air attache took fuzzy photos of the weapon and sent them back for analysis. The Raytheon team compared the missile with the parade watchers standing nearby to estimate its dimensions. Then it projected the capability of America’s smaller surface-to-air missiles onto a missile the size of the SA-2. After two days of computer modeling and simulations of performance curves, the team calculated the SA-2 could reach 90,000 feet, well above the U-2’s maximum flying altitude.

The following year, Abt found himself embroiled in another international controversy. Raytheon had been selling Hawk air defense missiles to Israel, but the Saudis decided they wanted them, too. Raytheon President Charles Francis Adams knew it would be good for business to sell to both sides, but he had a higher priority: would the sale threaten strategic stability? Increasing the risk of war wouldn’t be good for either side or U.S. interests. He would forego the revenue if the sale altered the balance of power. (It’s no surprise Adams would put national interests first: he was a direct descendant of John Adams and John Quincy Adams, 18th and 19th century father-son American presidents.)

Adams knew about Abt’s arms-control work and asked him to analyze the situation. Abt finished his report in a week. His conclusion: the sale would increase, rather than decrease, stability. Why? Accidental wars could stem from the presumed advantage of a preemptive first strike. Effective Hawk air defense batteries considerably diminished the likelihood of a successful first strike and, thus, its appeal. The Hawk system was strictly defensive. It couldn’t attack ground forces at all or aircraft more than 20 miles away. If both sides had the systems, they could worry less about a surprise attack. And they wouldn’t bolster their offensive firepower. Abt’s argument proved persuasive to Washington, the Arabs and the Israelis. It was consistent with sound arms control policy and the balance of power in the Middle East.

Sick of stalemates

By 1965, he had received his PhD. In the process of his work, he had evolved from a cold warrior weapons systems engineer to a defense strategy analyst to an international arms control policy planner and strategist. His exposure to the best minds in this area, though, led him repeatedly to see unsatisfying conclusions. “I never liked stalemates, or dead ends, especially if it could be everybody’s dead end,” he wrote.

His first stalemate: the B-70 Bomber Penetration Aids Project. The goal was to maximize B-70 penetration of Moscow air space. The bomber would have to evade Soviet fighters and missiles with speed, altitude and on-board countermeasures such as equipment for jamming (causing signal interference) and spoofing (sending false signals). Computer simulations found that at 70,000 feet and three times the speed of sound, the B-70s would be vulnerable to Soviet surface-to-air missiles. But both the B-70 and older B-52 could survive at the lowest possible altitude and at subsonic speeds because of radar blind spots at low altitudes.

(The 1964 satiric, black comedy Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb was accurate in depicting a low-altitude, B-52 nuclear bombing run – with actor Slim Pickens portraying Major “King” Kong – as being able to evade radar detection by the Soviets.)

But if a lot of U.S. bombers could reach Moscow, Soviet Bison bombers similarly would be able to reach the U.S. Abt’s conclusion: “Most American and Russian cities and their populations would be wiped out.” The Air Force agreed, but not the head of the Strategic Air Command, General Curtis Lemay. Gesturing with his cigar, he dismissed Abt: “Naw, young man, just give me altitude, just altitude, and we’ll make it to our targets!”

This was from the lips of a senior officer whose bombing campaign in Japan during World War II left an estimated 500,000 civilians dead and 5 million homeless, who had advocated bombing Cuban missile sites during the 1962 missile crisis and who supported bombing North Vietnam back into the Stone Age during the Vietnam conflict. Lemay noted that if the Allies had lost World War II, he would have been tried as a war criminal. Suffice to say, Lemay’s comments on altitude did not inspire Abt’s confidence in Washington’s nuclear strategy.

Another stalemate involved the Ballistic Missile Boost Intercept space-based, anti-missile system. In the early 1960s, Abt’s team designed a system of about 240 satellites that would circle the Earth in 300-mile-high orbits. Each had 20 infrared homing interceptor missiles. The cost: more than the entire defense budget. Its effectiveness was unknown and untested, but the best estimate – with everything working as intended – was 80% effectiveness. If 20% of the Soviets’ intercontinental ballistic missiles made it through, though, they could destroy 200 of America’s largest cities and most of the country’s population. Another dead end.

Branching out

With his new credential in hand, Abt pondered his next move – whether to stay in the comfortable confines of Raytheon or branch out on his own. Fear of failure dogged him as he mulled his future. But his ambition to have his own venture, his entrepreneurial bent, and his belief that his leadership could improve on what he saw at Raytheon triumphed over his anxieties. In addition, his frustration with military stalemates and his empathy for underdogs led him to shift his focus from the Cold War to the War on Poverty.

Abt’s wife at the time, Susan, a psychiatric social worker, supported Abt’s aspirations. His mother, not so much. She had gone through the German depression of the 1920s and the Great Depression of the 1930s in the U.S. She couldn’t fathom why he would want to leave a secure job to try something new. Most of those whose counsel he sought were supportive, however. So he took the plunge.

Abt’s vision for the new firm was nothing less than utopian: to create a world free of war and poverty. His strategy for moving toward this nirvana was hard-headed, though, using systems analysis, computer modeling and simulation methods for quantitative evaluations to improve social programs. Social science methodologies such as case studies and cost-benefit analysis delivered evidence-based interdisciplinary solutions for social and economic problems. One former Abt Associates employee described the firm as a mild-mannered social reform organization, an informal graduate school, and a profit-making enterprise.

The firm was a major force in developing ways to comply with performance requirements imposed on government contractors in the social policy arena. “His vision was to have kind of a think-tank like RAND, dominated by PhDs, that would push into all aspects of public policy to do monitoring and evaluation research on what the best policies need to be,” says Gary Gaumer, a health economist at Simmons University who worked at Abt Associates for 27 years. “That was critical to the development of the kind of evidence-based approach to policy that came to be in this country.”

What is remarkable – and generally gets little media attention – is the stunning progress the world has made toward Abt’s goals, though many factors other than Abt Associates’ work are responsible. According to ourworldindata.org, the annual number of war deaths has been declining since 1946, from half a million in the post-war years to 87,432 in 2016. The war Abt hoped to avoid was a nuclear war, and there hasn’t been one. Meanwhile, World Bank data show that the percentage of the world’s population living in poverty has plummeted from 36% in 1990 to 10% in 2015. To paraphrase a line in the play, Crazy for You, Abt was worse than a hopeless romantic. He was a hopeful romantic. And his optimism has proved surprisingly justified.

The first important task when Abt started the firm: coming up with a name. Acronyms were the trend at the time for similar organizations: RAND (Research and Development) or IDA (Institute for Defense Analysis). Abt tried out ISAC (Interdisciplinary Systems Analysis Company), but his colleagues hooted him down. Another idea was to use the name of his department at Raytheon: Strategic Studies Inc. But “strategic” sounded too militaristic and pompous; “studies” sounded too passive. A third approach was to use the founder’s name. Arthur D. Little and Bolt, Beranek and Newman were examples. Abt Associates was alliterative and unusual, which Abt liked. He thought there would be little confusion with the American Ballet Theater. (In fact, virtually everyone who hears the name these days thinks it’s an acronym – though not a dance company.)

Abt had the good fortune to start his firm with a reasonably solid foundation:

- a contract to design educational games for a non-profit starting up a middle school social science curriculum

- assurances from the Joint War Games Agency of the Department of Defense that if he kept together his Raytheon team, the agency would find funding to support the Technological Economic Military Political Evaluation Routine (TEMPER), the first computerized model of global Cold War conflict

- interest from the Army and Marines to continue financing his counter-insurgency training simulations

The path the company would take and its strategy, however, were not entirely clear to the staff in the early days. Educational games and Cold War conflict brought revenue, but not clarity. “There was not as much focus as Clark thought,” recalls Chris Hamilton, the poverty expert who worked at Abt Associates from 1966 to 2003. “By 1967–68, he was sitting there with a bunch of really smart people who could do a lot of things, but didn’t have a home turf.”

Hamilton, Abt veteran Steve Fitzsimmons and others say that as a manager, there was one thing Abt was really good at: hiring people who would turn out to be effective. “I think that’s the key to all kinds of success in all kinds of fields, but especially the one we’re in,” Hamilton says. Abt often said he would never hire anyone who wasn’t better than he was in at least one thing. And he said managers should always hire staffers who were smarter than they were. At Abt Associates’ 25th anniversary, Wendell Knox, a senior executive who later would become CEO, quipped that the staff wanted to congratulate Abt on his great success at consistently hiring people who were smarter than he was.

Abt was legendary for wanting to interview all new hires and asking them about the last three books they had read. He wanted to know if they read books. He was a voracious reader and had probably read one of the books or knew something about one of the authors. In the subsequent discussion, Abt could discern how smart and able the person was. Not that he was perfect at hiring. Peter Miller, a former Raytheon colleague and Abt Associates No. 2, says that while Abt hired capable people and rewarded them with added responsibilities, he sometimes hired impulsively. Miller often had to serve as the shovel brigade to clean up after the elephant parade.

Abt was progressive in his hiring practices, seeking out women and minorities to fill top slots. In 1986, women headed five of the company’s six government research units. “The rest of the world was hiring women to be secretaries,” Miller says. “Clark didn’t see them that way.” He gave them the same kinds of jobs as men. “One of the great things that era of injustice did for us was to bring a whole bunch of incredibly talented women to the company,” Miller says.

Part of Abt’s vision never really thrived: influencing military policy with tools such as war games. “We failed miserably to win defense contracts,” says economist Larry Orr, a former Abt Associates’ employee and the husband of current CEO Kathleen Flanagan. “I think it was because he hired a bunch of social scientists who didn't speak DoD's language.” It didn’t help that the Joint Chiefs of Staff had grown impatient with the TEMPER world conflict computer model, which at one point spit out that a nuclear war had broken out between Argentina and Greenland.

One notable exception: The firm’s research on revolutionary conflict, war gaming and simulation suggested that the United States' defeat in Vietnam was predictable. The research indicated that it would be virtually impossible for a numerically inferior defending conventional army to defeat a numerically superior and highly motivated guerrilla force operating in its own territory and backed by a larger conventional army in adjacent territory. But by 1967, the firm on its own initiative dropped all defense work to protest the Vietnam War.

Ushering in a new era

The other part of the vision – influencing social policy – did pan out. In spades. The reason: timing is everything, and President Lyndon B. Johnson had just launched one of his signature initiatives, the War on Poverty. Announced during LBJ’s State of the Union address the year before Abt Associates’ founding, the War on Poverty encompassed a broad range of programs. The legislative package created the Office of Economic Opportunity to administer anti-poverty funding at the local level; the pre-school program Head Start; Medicaid, a health program for the poor; the job-training program Job Corps; and a huge increase in Social Security spending, which caused the poverty rate for seniors to plummet from 28.5% in 1966 to 10.1% today. Congress added some projects based on anecdotes or a lawmaker’s idiosyncratic or political interests.

In sum, Washington was throwing vast sums at programs to tackle social ills. “Most didn’t accomplish very much,” Hamilton says. “People started asking why weren’t they working or were they working and we can’t see it.” In fact, poverty rates did decline, but they had been dropping before the War on Poverty. Someone needed to help the government determine if the programs were the cause of the continued drop and if not, how to fix them.

The best way to evaluate such programs is a rigorous methodology known as randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Take a group of similar people, assign some randomly to a program (the treatment group) and exclude others randomly from the program (the control group). If the treatment group does better, and participation in the project is the only difference, you can conclude the program was the reason.

This scientific approach applied to War on Poverty programs heralded the dawn of a new era. At the time, institutions such as the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard didn’t exist. Policy research didn’t exist as a field or as a market to meet this emerging need. Abt knew his crew was positioned to lead the charge. “Who better to exploit a new market than those who don’t currently have one?” Hamilton asks. “Take smart people accustomed to sitting up all night writing term papers; the government issues a request for proposals, and they sit up all night writing a proposal.”

Abt’s ability to attract smart people was not limited to staff. The board boasted such luminaries as Kenneth Arrow, a Nobel Prize-winning economist, and Daniel Bell, a Harvard sociologist and one of the leading post-war intellectuals.

While the board provided insightful strategic guidance, it was the stellar staff that won as many as half the proposals Abt Associates submitted in those early years. Those efforts helped the firm grow rapidly. In 1965, Abt Associates had gross billings of $205,097 and profits before federal taxes of $22,665. By 1967, billings skyrocketed 550% to $1,127,685 and profits before taxes ballooned 510% to $115,539. Orders similarly grew more than 500%, from $270,000 to $1.4 million. Those three years exemplified what later was captured in the iconic ying/yang symbol in Abt Associates internal presentations: the seeming conflict but actual interdependence between financial health and the mission. Abt had planned from the start to create a for-profit company that would have the resources to help the world’s most vulnerable. And the theory was working in practice.

Indeed, in the early 1970s, Abt Associates was prominent in the market policy research market and perhaps even dominant, Hamilton says. Policy discussions within government at the time were intense, and politicians, social scientists, and academics hungered for facts. Liberal supporters of the programs wanted data to justify the War on Poverty programs, while critics in the Nixon Administration wanted data to show the programs were failing so they could kill them. Thus, there was bipartisan support for the kind of work Abt Associates was primed to perform.

In 1972, for example, Abt Associates conducted the nation’s first large-scale social experiment: an RCT of housing subsidies for renters to determine the effects of supporting housing demand, rather than subsidies to builders to increase supply. The findings led to the Section 8 housing program, which since 1974 has been the nation’s largest low-income, safety-net housing program. Under the program, renters spent a percentage of their income on rent, and the federal government paid the difference between that amount and the actual rent.

The social scientists’ focus on methodological rigor and RCTs led to some quirky incidents. For example, as Abt embarked on a project in Los Angeles, one client asked what the control group for the city of Los Angeles would be. A similar concern with methodological rigor led Abt, at the height of the Surgeon General’s anti-smoking campaign in the 1960s, to decide that the Surgeon General’s evidence showed a correlation between smoking and cancer, not causation. Conclusive evidence would require an RCT. Senior staffers balked, arguing you couldn’t assign people randomly to smoke or not to smoke. Abt’s reply: “The military could. Let’s talk to DoD.” Such incidents led one wag to write on a Cambridge headquarters bathroom stall: “Abt Associates: Analysis in Wonderland.” “That’s a pretty good description of the place,” says Steve Fitzsimmons, an evaluation specialist who left Abt Associates in 2002 after 36 years and was the firm’s 12th hire.

So Abt Associates and its CEO, with his fertile and sometimes febrile mind, were off and running. But the contracts tended to be short-term, and each year the company bet the farm on its proposals. If the firm didn’t win enough of them, it could have gone belly-up. Abt was not averse to risk. He often said, “If it’s worth doing, it’s worth doing badly,” Abt’s son says. “It doesn’t mean he has low standards. It means if he thinks it’s something to do, he won’t let the risk of failure stop him from doing it.”

The firm had another motto that buttressed Abt’s mantra: Ignorance is no bar to action. “We were smart. We were cocky,” says Peter Miller, Abt Associates’ second-in-command at the time. “We would take on most anything.”

Risky business

The stunning trajectory of those heady first three years screeched to a halt in the fourth year. The reason: the disastrous acquisition of Audio Video Industries Inc. (AVI), which lost more money in Abt Associates’ fourth year than the accumulated profit of the first three years. Abt as the CEO took full responsibility and was particularly harsh on himself, calling it a foolish decision and bad judgment. “I was driven to accelerate growth by preparing for an IPO [initial public offering], seeking the venture capitalists’ Big Payoff,” he wrote. Abt blames himself for not doing sufficient due diligence and assuming the adviser who brought him the deal had.

The deal also may have been a triumph of hope over experience. In trying to understand how he got involved in what he called a “terrible acquisition”, Abt concluded that AVI had convinced him on the idea of expanding the market for Abt Associates’ educational and training games by selling them to AVI’s closed-circuit TV customers. Commercializing his simulation games was a long-standing dream of Abt’s, a road taken many times and aborted as often. The lesson was to stick to government work and resist commercial products. (Abt periodically ignored the lessons and lost millions in other ill-fated ventures.)

Perhaps nothing shows Abt’s penchant for risk better than one critical aspect of his hiring approach, which is virtually unheard of for a CEO today. He hired a bunch of “no men” instead of “yes men”. “There were half a dozen folks whom he would call into his office and float an idea on, and they would shoot it down more often than not and tell him what was wrong with it,” former company vice president Chris Hamilton recalls. Harvard sociologist and former board member Daniel Bell once said that the board’s function was to restrain Abt from taking excessive risks based on his enthusiasm for the latest technological innovations. Retired executive Peter Miller recalls that after meetings in which Abt would tell people to do half a dozen things, the staff would come to him, and Miller would give a green light to some and a red light to others. “It was clear we worked that way,” he said.

Sometimes Abt bypassed the no-men. Take the time he asked senior staff to arrange a meeting with Navy admirals without saying why. Abt had sufficient credibility with the brass for them to agree to the meeting. Abt walked in and proposed a submersible aircraft carrier to reduce carriers’ vulnerability and add an element of surprise. The meeting went neither long nor well, but the concept was eventually published in Proceedings, the monthly journal of the U.S. Naval Institute.

Just as Abt wasn’t always right, the naysayers made mistakes, too. Consider the incident when Abt dragged a bunch of people into his office to discuss a brainstorm he had: solving the unemployment problem by training the unemployed to start their own businesses. The assembled group of senior staff thought it was a crazy idea. They cited the expense and a host of other reasons it wouldn’t work. After about an hour and a half, Abt gave up. “The lesson I drew from it was that it took 11 vice presidents to convince Clark that he had a bad idea,” says economist and former employee Larry Orr. “Fortunately, we had lots of VPs.”

A few years later, the Department of Labor put out a request for proposals for a project to train the unemployed to start their own businesses. Abt Associates won the contract. “Much to our own surprise, it showed that this was a cost-effective idea,” Orr says. “Self-employment training is now an allowed service under Unemployment Insurance.”

Author, author

In 1970, Abt published the first of his 10 books, Serious Games, which triggered a breakthrough in how games and simulations can train decision-makers in industry, government, education, and personal relations. Time magazine had highlighted his views in an interview several years before publication, and his approach took hold among academics, business leaders and gaming experts worldwide. “As an inventor of serious games played by serious people such as State Department or other cabinet officials or the military, Abt has become an ardent advocate of the usefulness of games as a pedagogic device at all stages of life,” wrote Kirkus Reviews, a trade publication that previews books. “For children, games may be more instrumental than lecture and rote learning methods and for the children of the poor, they may be the most effective way of instilling enthusiasm, cooperation and conquering fears.”

In classrooms in poor neighborhoods, the games brought out the intellect of some students who otherwise sat quietly at the back of the room, never showing the spark that the games elicited. They were able to show their understanding of the behavior of others and their motivations and plan strategies accordingly. It may not have been traditional book learning. But it enabled the students to demonstrate and refine a tactical shrewdness that, if encouraged in school, would enable them to succeed outside of the classroom.

Six years later, Abt published another groundbreaking volume: The Social Audit for Management. Its genesis was in 1971, when Abt introduced social accounting to Abt Associates and the business community. He wanted to create and measure efficiently an organization’s social benefits.

So he developed a quantitative approach for evaluating the social benefits and costs of an organization’s operations for five constituencies: employees, stockholders, clients, neighbors, and the general public. On August 19, 2019 – nearly 50 years after Abt’s 1971 social audit – the Business Roundtable’s leading CEOs caught up to him, redefining the goals of a corporation to expand beyond profit maximization. The goals also should include delivering value to customers, investing in employees, dealing fairly and ethically with suppliers, and supporting local communities.

Forward thinking

Such prescience was hardly an aberration for Abt. He opened a solar-heated office in 1976, well before it was financially viable. It never paid back the investment, but years later when solar heating took off, it would have been a sound strategy.

Similarly, in 1987 after his retirement as CEO, Abt took over Abt Books and as its publisher pioneered the production of scholarly CD-ROMs such as Drugs and Crime and fine arts CD-ROMs such as the Smithsonian Institution’s National Portrait Gallery on CD-ROM. The idea was to sell such “books” for a fraction of the cost of hardcover editions. But potential customers didn’t yet have the equipment to read the CDs, and the “portable” player Abt wanted to offer – about the size of a large suitcase – cost more than buying the books would have. After publishing about 100 social science books and four CD-ROMs, the unit closed in 1990. Soon after, most computers had the CD drives needed to have made a go of the business.

“It’s like he could see in the future,” says evaluation specialist and former employee Steve Fitzsimmons. “He just couldn’t see the timeline.” You need the right combination of technical skill, marketing and marketplace readiness for a product. From a business standpoint, “a great idea before it’s time is a lousy idea,” he adds.

Sometimes it was Abt himself who was the “no-man”. This happened most often with ideas for forays into the commercial sector, perhaps because he had been burned so badly. But some people had good ideas, and “he just shot them down”, Fitzsimmons says. At least one person left the company as a result. Abt wanted to let a thousand flowers bloom, Fitzsimmons adds, but “sometimes he kept weeds and didn’t plant what was most promising.”

A polymath company

Overall, Abt managed to create a firm very much in his polymath image. “Abt Associates carries this man’s DNA,” says David Ellwood, former board member and former dean of Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government. The firm dove into a breathtaking range of areas.

- It had a contract with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) that focused on using NASA technology for energy efficiency in urban construction.

- Together with Stanford Research Institute, it conducted the nation’s largest educational experiment: an evaluation of the education for 79,000 disadvantaged children in 180 communities from Grades K to 3.

- It conducted a landmark study of the societal costs and benefits of federal regulation of the consumer banking industry.

- For the city of Houston, it created a busing plan to integrate the schools.

- Abt Associates laid the groundwork for the Early Head Start Program with an evaluation of a child-care program.

- It developed measures to assess the effectiveness of basic research projects and to forecast the probability of success of alternatives to basic research involving the National Science Foundation.

Staffers for the most part had their specialties and worked heads-down on their narrow projects to bring in revenue, but Abt’s mind knew no boundaries. “The way his brain worked, it was out of the box, and I guess that’s part of being the unique person that most entrepreneurs are,” says health economist Gary Gaumer, who worked at Abt Associates for 27 years. Abt, he added, saw “opportunities where other people are so narrow that they never thought about it.”

- He mused about the sale of air rights to build structures over parking lots and roads long before the world was ready for it.

- He wanted to convert one of the company’s courtyards to grow saffron to test high-yield agricultural products.

- Abt inspired game simulations to illuminate the motivations, considerations and actions of stakeholders. One simulation conducted around 1970 involved transportation in the northeast and Canada that, quite sensibly, ignored state and even national boundaries. Transportation experts from the states and provinces participated, along with national government representatives from commerce, infrastructure, and transportation agencies. Transportation modes included road, rail, air and water. Participants got a picture of the whole regional transportation system and the surprising types of external events that could derail transportation plans. They also discovered how many moving parts there were in the decision-making process – many of which had not been apparent beforehand. And the networking during the simulations contributed to regional cooperation.

- A long-time environmentalist credited with planting more than 1,000 trees during his tenure at Abt Associates, he won the Henry David Thoreau Grand Award for Commercial-Industrial Landscaping from the Associated Landscape Contractors of Massachusetts for the landscape architecture of Abt’s Cambridge headquarters.

Abt’s creativity extended to employee benefits. He offered free breakfasts and as much as eight weeks of vacation after 20 years of service. Eventually he dropped the free breakfasts in exchange for dental care. In 1975, he created an employee stock ownership plan and employees also had individual retirement accounts and 401 (k) retirement options. The firm covered abortion care and offered paternity leave long before other employers. It offered generous tuition reimbursement. And in the parking lot was an electric car that employees could borrow for the weekend. Abt “pioneered in taking an interest in employee benefits,” says Fitzsimmons.

Health expert Henry Goldberg’s favorite benefit was a garden cultivated over a former dump on an adjacent plot of land purchased by the firm. The original plan was to construct another building, but there wasn’t money for it. Instead the company grew produce that the cafeteria used, and employees could sign up for plots to grow vegetables and flowers. “Only one person got busted for growing marijuana,” Goldberg says, adding that the police just told that person to get rid of it.

A sharp rise in healthcare costs in the late 1970s and early 1980s spelled an end to this gravy train. Abt’s collaborative solution was to use a benefits tool for his employees that Abt offered to clients. The firm’s overhead for pensions, health costs, and vacations needed to be industry-competitive, so Abt used the tool to create a hypothetical budget listing all options with their costs. The tool educated the entire company – then about 650 employees – about the issues and tradeoffs needed to cover healthcare and other costs. Employees then chose which benefits they wanted, given the budget ceiling. For example, they decided to jettison free coffee. “They got to be complicit in the crime,” says Wendell Knox, the retired former CEO.

Abt’s exit

In 1986, Abt switched gears. Instead of advising policymakers, he wanted to be one. He transferred responsibilities as president and CEO to Walter Stellwagen (but remained board chairman) so he could campaign as a Republican for the House seat Speaker Thomas P. "Tip" O'Neill (D-MA) was vacating. O’Neill, who was retiring, told Apt’s wife, Wendy, not to let him run. Another red flag: when Abt defended O’Neill to a right-wing Republican, the response was, “You stink!” Abt, of course, was not dissuaded and lost by a 3-1 margin to Joseph P. Kennedy II, the nephew of President John F. Kennedy. In retrospect, Abt thinks that running for Congress and reducing his role at the company was his biggest mistake. “I lost interest in expanding the business,” he says.

But he still had his passion for national security and socio-economic policy. In the early 1990s, he organized and directed four Russian-American Entrepreneurial Workshops in Defense Technology Conversion for nuclear weapons scientists. Nuclear scientists from Los Alamos and Lawrence Livermore labs and their Russian counterparts brainstormed to commercialize their work so that the Russians would not look to make money by selling their nuclear know-how to rogue nations. “They worked together quite well,” recalls health economist Gary Gaumer. “They were the same kind of people. Not a nickel’s worth of difference.”

The theory may have been better than the practice, however. The teams developed product ideas, put together business plans, and made presentations. Abt board members playing the role of venture capitalists listened to the pitches and provided feedback. But at one point, the Russian co-sponsor, the minister of nuclear power, a heavy-set, Nikita Khrushchev-like figure, invited the workshop faculty into his office for what everyone but Abt thought was a perfunctory meeting. Abt proceeded to lecture the minister in English, which he didn’t understand, on the need for safe nuclear power and for developing viable careers for Russian nuclear scientists. After a short time, the minister stood up, said the meeting was over, thanked the Americans, and walked out. Abt thought it was a great opportunity to brief a powerful guy who could get things done, but others were a bit embarrassed. “I’m sure the guy never got talked to like that in his whole life,” Gaumer said.

Another problem: Abt and the Pentagon differed with Moscow about the way forward. Russia upset then-Defense Secretary William Perry when it gave Iran nuclear power plants. Abt, who had been working with Perry, asked Viktor Mikhailov, the minister in charge of Russia’s nuclear program, what he was doing because the U.S. and Russia were supposed to contain the spread of nukes. “Professor Abt, you and we have so many thousands of nuclear weapons,” Mikhailov replied. “They might get one or two. It’s so small. Why are you worried about it?” Not the answer Washington wanted.

Still, Washington and Moscow reached agreement on dozens of contracts to keep the Russian scientists busy. One was for Russia to export surplus highly enriched uranium, which the U.S. would dilute and use as reactor fuel. It was a win-win: Russia got money and the U.S. saved the cost of mining uranium. Many of the deals, however, never bore fruit.

Other ideas didn’t even reach the contract stage. Abt and the deputy director of the Los Alamos National Laboratory pushed the idea of having Russian mathematicians help the biotech industry with drug discovery modeling and simulation. They set up a meeting in Cambridge with biotech pioneer Craig Venter, who led the first draft of the human genome. When Abt presented what he thought was a brilliant idea, Venter laughed out loud. “You mean you expect our highly competitive drug discovery industry to share their secrets with Russian scientists?” Venter asked. “I realized it was a really dumb idea,” Abt says now. “And so did my colleague from Los Alamos.”

The irrepressible Abt stayed engaged in socio-economic policy, too. In 1997, he conducted research on renewable energy and environmentally sustainable economic development and presented papers in the United States, at the United Nations, and in China, Malaysia, Kazakhstan, and the Philippines.

Enter Wendy

Just as the business and his ideas had ups and downs, so did his personal life. His two-Porsche, first marriage to Susan, the psychiatric social worker, ended in divorce in 1970, though it ultimately was amicable. “She got her car and the house. I got the company and my car,” Abt says. Abt and his ex-wife still run into each other frequently at the Harvard Institute of Learning in Retirement.

While he was separated and heading for divorce, he felt at loose ends. A turning point, bizarrely, was a journal article he wrote in 1969 about a systems analysis approach to calculating the cost-effectiveness of education. At the time, Wendy Peter was a young program officer at the Africa-American Institute in New York City. She had been in Operation Crossroads Africa when she was 17 and had kept up her interest in African development. She had sold the idea of a systems analysis of the school dropout problem in French-speaking West Africa and had raised money from the U.S. Agency for International Development and the Canadian government. The only problem: she knew nothing about systems analysis. “I had oversold it,“ Wendy says. “A not untypical situation for me.”

Abt’s article was just what she needed. She took a plane to Boston and made an appointment to recruit Abt. But he was busy, so when she arrived at 11 a.m., he told his secretary that she should see a colleague in a nearby office who had led high school programs in Uganda. After 10 or 15 minutes, Abt got a call from his colleague: “You ought to meet this lady,” he said. “She’s very interesting.” Abt declined. Ten minutes later the colleague called again, this time with an urgent tone: “Clark, you really ought to meet this lady.”

Abt decided to break off his work and walk around the corner. He walked in, introduced himself, apologized, and said he just wanted to say hello. “And there she was,” Abt recalls. “A beautiful woman in a sans-culotte tweed suit. Straight lustrous brown hair. Beautiful face, beautiful legs and talking very well, assertively about this project.” Abt listened for a couple of minutes, then detailed for two hours how to perform the systems analysis.

Wendy had to get on a plane back to New York and thanked him for his support, mentioning she would meet her boss the next day. Abt said he had to be in New York the following day (he didn’t really) and would be happy to meet with her team. “I was smitten,” he says.

After the New York meeting, Abt asked her if she would like to have dinner. She was shocked and said she never went out with married men. “I grinned and said, ‘But I’m not married,’” Abt says. Two years later they married, and eventually she joined Abt Associates after partnering with the firm to win a contract for educational technology in Africa.

Nearly 50 years and two children later, they are still together at home. But work no longer is a family affair, thanks to a corporate crisis the Reagan Administration created. Sharp cuts in social programs put the firm, then with 1,000 employees, at risk. Revenue fell roughly 50%. Abt’s advisers told him just to hunker down because government funding eventually would come back.

Waiting was not Abt’s style, though, so he rejected his advisers’ recommendations. Instead, working with Wendell Knox, at the time a vice president and area manager, he decided to try to sell the firm’s skills to private industries in turmoil: banking, healthcare and automotive. Banks were undergoing deregulation. Healthcare costs were soaring, and every CEO wanted to get them under control. And the auto industry was under assault from Japan. Abt and Knox thought they could sell the firm’s ability to collect data to analyze markets and predict customer behavior – and they did. “I saw Clark come from a gloomy place to an exciting place,” Knox says.

But the new business wasn’t enough to stabilize the ship. The company had to pare everyone’s hours or lay off up to 400 people. Both the staff and leadership thought layoffs were the better option. It was impractical for everyone to take a 50% cut in pay. Lots of people would simply leave – perhaps the wrong people. Abt realized “it was critically important to retain the company’s core skill set, to retain our top brains,” Knox says. At the time, Wendy was planning to return from maternity leave but decided it was inappropriate with so many people being laid off. So she ended her eight-year tenure at Abt, where she had focused on education and youth employment, directing analyses of the impact of President Richard Nixon’s revenue-sharing school programs.

The hallmarks of Abt’s business approach – risk-taking, evidence-based decision-making and quirky impulsiveness – are evident in his personal life. For example, his wife says Abt likes gadgets and machines that do more than one thing: a can opener that’s also a vase. One day he was driving in Watertown near Cambridge and spotted a car with a “for sale” sign on it. He immediately went to a bank in Watertown Square, withdrew money, and bought it. It was an amphibious car, which operated in the water and on the road. But it was an older version, and it leaked. “It was pretty hilarious to be riding along Storrow Drive and then go into the Charles River,” Wendy says. “It was fun and then fun when you had to bail. It was less fun when he took the kids and their friends out.”

A while later on Wendy’s birthday, money was tight but Abt knew she liked elegant cars. So he bought a 1939 Bentley for a few thousand dollars. Unfortunately, 1939 was not a good year for Bentleys. It broke down so often they needed a flatbed to haul it to the mechanic. Eventually Wendy issued an edict: She never wanted to be in a vehicle that people wave at or take pictures of. Nor did she want to be in a position that makes people burst out laughing.

Abt applies his decades of hard-headed data analysis to personal decisions. Several years ago as a weekend approached, he faced a medical emergency – a twisted small intestine – that required surgery quickly. In the emergency room, as Abt was literally dying, he rejected any precipitous action. He knew studies showed that operations on a Friday afternoon did not turn out well. He didn’t want to miss his Sunday tennis game. And if he couldn’t talk to his primary-care provider, he would not consent to the surgery.

There was one more issue. His condition normally was found in babies. He asked the surgeon how many times he had performed the surgery, and the answer was hundreds of times. Then Abt asked the doctor how many times he had performed it on someone his age. The answer: never. That, unfortunately, just added to Abt’s certainty and defiance. (Of course, he seemed to ignore one other bit of relevant evidence: what happens to people with untreated twisted small intestines.)

He threw the hospital into complete chaos, as Wendy recounts the story. The deputy head of surgery was in tears. “I went to medical school to save lives,” the doctor said. “Now you’re not letting me do it.” No one else given the facts and information would have had the self-confidence to exercise his own independent judgment, Wendy says. She was ready to have him committed to a psychiatric ward so she could authorize the surgery. But she worried that if a shrink asked if he ever acted like this before, the answer would have to be: “Sure, all the time.”

All the while, the clock was ticking. The monitor showed his intestine deteriorating, and once it was gone, so was Abt. What saved him? His son, Thomas, showed up in the emergency room and reminded Abt that as a manager and executive he frequently had to make decisions under conditions of uncertainty and missing information. As Thomas talked, Wendy could see Abt’s shoulders squaring. He relented and allowed the operation to go forward. “One of the hallmarks of my dad is intellectual flexibility,” Thomas says. “He is intellectually confident, but when he is convinced he has made a mistake, he will change his opinion – and abruptly.”

In 2006, Abt retired from Abt’s board. The board had evolved from an advisory body to a governance body and instituted rules such as term limits for directors and a mandatory retirement age of 75. Abt was grandfathered briefly, but eventually had to leave.

His namesake company continues to thrive as it branched out into diverse areas. Today it is far more international than it was in Abt’s day. With more than 3,600 employees working in more than 50 countries, Abt Associates:

- sprays insecticide and distributes insecticide-treated bed nets in two dozen countries to combat malaria while performing entomological studies to analyze mosquito resistance to insecticides;

- has fought Zika virus;

- provides technical assistance to dozens of countries trying to improve their health systems and healthcare delivery of everything from family planning services to HIV to tuberculosis;

- helped the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention draft opioid prescription guidelines to reduce misuse while providing medication to those who need long-term pain treatment;

- analyzed the environmental impact of the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico;

- conducts the annual homeless survey for the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development;

- collects survey data for the ABC/Washington Post political polls;

- wrote a chapter of the recent U.S. National Climate Assessment;

- found that a 19% cut in federal prison sentences would have no impact on recidivism and would have an enormous positive impact on the individuals, their families, their communities, and taxpayers; and

- used machine-learning to analyze 10,000 comments on a proposed U.S. Environmental Protection Agency regulation.

If you want to evaluate Abt’s impact, former employee Steve Fitzsimmons says, look at what the firm is like now. “It’s a pretty good measure,” he says. Adds former board member David Ellwood: “Many of the great institutions of the world that really matter are blessed with a founder whose values and vision just become part of the culture. Clark was such a person.”

Abt’s proud progeny