Updated: Update

Published: September 2012

A fast-growing global sport

Sassy, flashy roller derby chicks skating like hell and kickin' ass

By WARREN PERLEY

Writing from Montreal

A discreet sugar skull tattoo on the svelte left calf of our waitress caught my eye. I was about to be sucked into the vortex of one of the fastest-growing women’s sports in the world — flat track roller derby. A punk subculture of fishnets, tank tops, spandex and short-shorts stirred in a frenetic cocktail of full-body contact skating.

As she sets down my lunch special of grilled salmon with vegetables and rice on the terrace at Otago Café in west-end Montreal, nothing about Amy’s 5 foot, 7 inch physique or demeanor indicates that she is an athlete. Shoulder-length, straight brown hair, narrow waist and long, slim legs. She is soft-spoken and low key. She wears no jewelry, other than simple black plug earrings. Her shoulders are not particularly muscular. I notice some bruising on her upper arm.

It could easily be the body of a fashion designer, which is why she moved to Montreal in 2005 and enrolled at Lasalle College. In her late 20s, she seems shy, the youngest in a family of three siblings whose two older sisters are mothers back home in Assiniboia, Saskatchewan, a small town 60 miles south of Moosejaw near the U.S. border.

Her mom, Marjorie, a piano teacher, tried her best to interest Amy in a musical career, but her youngest daughter was by her own admission “a little stubborn” and “didn’t like being told what to do.” Perhaps that independent streak should have been the first indication that her little girl was a non-traditional individual, unlike her conservative mother and father, a loans officer with the Agricultural Credit Corporation of Saskatchewan.

There is a Latin phrase used by St. Augustine regarding the Fall of Man: felix culpa, which has been interpreted as “fortunate fall”. In ecclesiastical circles, it refers to the fact that the disobedience of Adam and Eve in eating the apple from the Tree of Knowledge and being expelled from the Garden of Eden turned out to be a fortuitous event because it led to the possibility of redemption through Christ, the central tenet of Christianity.

In secular vernacular, felix culpa could be translated to mean “fortunate fault”, referring to something which appears at first glance to be bad, but actually turns out to be good: for example, people rebelling against societal norms which have become corrupted by avarice and self-aggrandizement.

For many middle class women, such as Amy, the free-wheeling world of roller derby reflects their conscious decision to reject traditional conservative values which do not respond to their needs. This is a common theme in roller derby circles: women from mixed backgrounds and ranging from their late teens to early 40s, snapping shackles which have restrained them physically, emotionally or sexually.

The Montreal Roller Derby, where Amy plays, is part of the Women’s Flat Track Derby Association (WFTDA), founded in April 2004 in Raleigh, North Carolina as a non-profit organization which now includes 156 member leagues across the U.S., Canada, Europe, Australia and New Zealand. There are thousands of women playing in more than 1,200 amateur leagues worldwide, with new converts arriving every season. There are even hopes among organizers that it could eventually become an Olympic sport.

The majority of the leagues are non-profit, with revenue generated from ticket sales, concessions, merchandise and sponsors going towards expenses. Most leagues are run by skaters with democratically elected boards and committees. This strong Do It Yourself (DIY) entrepreneurial ethic is perhaps indicative of the cynicism that average, honest folk feel these days towards the greed of big business and the corruption of many politicians. The WFTDA’s motto is: “The Revolution Continues.” The bottom of its web home page reads: “Real. Strong. Athletic, Revolutionary.”

Most participants, like Amy, get involved after a friend who plays the game invites them to a match, where they discover a fast, physical sport with an appealing, post-game camaraderie. After donning skates, pads, helmets and mouth guards, they’re reborn as roller derby chicks with colorful derby names, such as Amy’s “Sneaky Devil”, vying for one of 20 spots on a team. Fourteen players dress for each game.

On a sweltering Saturday night in July, I am among those lining up at the old Saint Louis hockey arena on Sainte Dominique Street in the working class, multicultural area of central Montreal, known as the Mile End section of Le Plateau, to watch Sneaky Devil and her teammates on La Racaille take on the defending champions, Les Contrabanditas. It appears to be a sellout with as many as 800 fans ranging in age from their early 20s to the mid-40s, about evenly split between men and women.

The low admission price — which ranges between $10 and $15 in the Montreal Roller Derby — with zany halftime spectacles built into the shows attract exuberant fans to witness serious athletic competitions. Some larger venues in the U.S. report sellouts numbering well above 2,000 fans.

The DIY ethic is apparent as soon as I walk into the lobby where I see Tabarnouk, Magnum P.E.I. and Al Strapone, all players with Les Filles du Roi, selling roller derby t-shirts for $20 each. The drink and snack concessions are also doing a brisk business, with beer selling for $3 a can or two for $5. Pizza slices go for $4 each. Before the night is out, close to 2,000 cans of Pabst Blue Ribbon beer, a league sponsor, will have been quaffed. For those fans craving stronger spirits, there are shots of vodka and scotch. Teetotalers opt for bottled water or organic lemonade.

What’s in a name?

I watch intently as each team warms up, with skaters in short-shorts and camisoles lapping the concrete oval which has a circumference of 136.5 feet around the inside and 248.5 feet on the outside. Everything in the arena is colorful, starting with the mismatched uniforms with the players’ derby names stenciled on the back. Roller derby names run the gamut from edgy to funny. All are creative escapism from monotonous daily routines. Ninja Simone, Dame of Doom, Killer Kozac, Raude Rage and Toxic Tea play for Les Contrabanditas. La Racaille has Nameless Whorror, Greta Bobo, Russian Cruelette and Banana Havoc among its ranks.

There are a few leagues where players use their real names, thinking it might encourage the public to take the sport more seriously. But in Quebec, skaters roll by their derby names, which is how I refer to them because that is the way they prefer to be addressed and because I don’t think it impacts on the seriousness of their athletic endeavours any more than do the nicknames applied to colorful players in some professional sports.

Even the team names are colorful, such as La Racaille, which translates into English as “delinquents, misfits,” or “scum”. Their website describes them as “a gang of shit-disturbing street punks on wheels…untamed, sexy, street-wise chicks, faster than lightning and itching to kick some ass.”

I have a special interest in seeing how Sneaky Devil, No. 666, does in this her first full season of play in 2012 after plunking down $300 in August 2011 for equipment needed to compete at boot camp prior to being drafted by La Racaille. Annual fees of about $400 cover league expenses, including travel and injury insurance.

When she first told her parents that she was playing roller derby, their reaction was, “Oh, that’s nice,” thinking she was roller-skating. Even now, almost one year later, her mother says she tries not to think of possible injuries.

Make no mistake about it; this is a rough sport. Most injuries are not too serious, involving scrapes and bruises. But there is the occasional broken bone and torn ligament. The women usually suck it up and continue their playing careers after recovering. Concussions, however, are a growing concern, with players starting to switch to professional hockey helmets, which provide more protection than the thinly cushioned roller derby headwear.

When I ate at Otago the day before the Saturday night match, Amy predicted that this last game of the regular season would be a close one, even though it was meaningless in the standings. Both teams were already scheduled to meet for the league championship two weeks later.

Skate to the musicIt’s a long journey to the roller derby track in cosmopolitan Montreal from the isolated Prairies. Her team biography says she was “born during a dust devil prairie fire in the badlands of Saskatchewan”, a piece of prose her mother laughingly calls “very entertaining and inventive.”

Marjorie did her best to turn her youngest daughter onto a musical career. First there were a couple of years of casual instruction on their European-made Wagner piano, but Marjorie told me in a telephone interview that her daughter didn’t study the music books as often as she would have liked.

She was better at the flute, playing for a couple of years in a community band, but she lost interest in that as well. Then she took up with the trumpet for a year or two. She was “alright”, but “didn’t practice enough.” Neither mom nor daughter knew it at the time, but this girl was destined to be a roller derby chick!

Fairly athletic as a teenager in Saskatchewan, she played baseball, volleyball, badminton, as well as track and field. She tried her hand at kick boxing in recent years, but it’s quite a different athletic challenge to roll around an oval on quad skates bodychecking opposing players to spring one of your own players, known as a jammer, by them. Every opposing player passed by your jammer, identified by a star on each side of her helmet, is a point scored for your team.

As I await the start of the game in the press section at rinkside, T-Bo and Chris, DJs with The Baron & Big Dog on Campus, keep the mood raucous with their Golden Oldie rock selections blaring through the PA system: AC/DC’s Highway To Hell; ZZ Top’s Beer Drinkers And Hell Raisers; Alice Cooper’s I’m Eighteen.

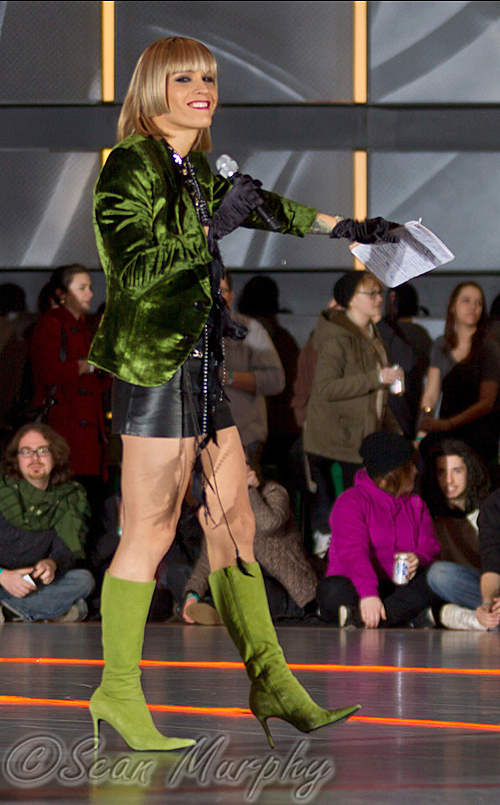

If the players, fans and music haven’t prepped me for a night of offbeat entertainment, one glance at league communications director and play-by-play announcer, Plastik Patrik, tells me this is going to be a screecher!

Green lace tank top, black and green spandex pants with a black glitter sash and high heeled booties. With his heavy mascara, blonde-bobbed, shoulder-length wig and perfect ruby red lips, one would be hard pressed to find any double X chromosome human to match his flamboyance.

Unlike public address announcers in professional sports who are unseen, those in roller derby operate at trackside, very much part of the spectacle — and Patrik thrives on it! This night, he was calling the game in French, while the alternate English play-by-play was done by Simple Malt Scott. I scribbled no descriptors about Simple Malt Scott in my notebook, meaning he dressed like a man and wore no makeup.

On the other hand, Patrik, a fluently bilingual, gender-bending DJ and party host sporting a conspicuous, blue dragon tattoo on his back, as well as a discreet ink illustration of an atom amid stars on his muscular left arm, filled up quite a few pages in my notebook. I’m told by a player that when Patrik travels to the U.S. to call the play-by-play, he leaves his blonde wig, makeup and finery in his travel bag rather than risk provoking straight-laced border guards.

Are we hot?Between the sauna-like temperature in the arena, the pulsating rock music and the kaleidoscope of eye candy, my senses are overwhelmed. I douse my fire with a Pabst Blue Ribbon 2-for-$5 special.

I am discovering first hand that while women’s roller derby is primarily a sport, it’s also a lifestyle and an open attitude; the concept of the big tent. It’s about empowering females of all races, nationalities, religions, sexual orientations, ages and body types by providing positive athletic role models.

Women’s roller derby leagues around the world are grass roots organizations. Money may be in short supply, but passion abounds. Bone Machine displays that deep-felt emotion as both a player with the New Skids On The Block, the Montreal Roller Derby’s all-star team, and as coach of La Racaille.

The New Skids, Canada’s best women’s roller derby team, travel all over the U.S. and Europe playing the best foreign teams. The Sexpos, their de facto farm club, also travel — mostly to the U.S. East Coast — for inter-league games. Neither the New Skids nor the Sexpos participate in regular season games or playoffs against the Montreal Roller Derby’s three home teams because they are just too good, although individual players with the Sexpos are allowed to skate for any of the three home teams. Players who have been on the New Skids for more than one year are not allowed to suit up for a home team.

Instead, some of the New Skids, like Bone Machine, volunteer to train and coach the three home teams — La Racaille, Les Contrabanditas and Les Filles du Roi [translated as “Girls of the King”]. The home teams play each other twice during the season, which starts in April and culminates with a championship match in early August. Each also plays one out-of-town team, which could be from Boston or Vermont, for example. In total their season is five games, with practices three or four times a week.

Bone Machine, wearing a peaked captain’s cap and dressed in a green tank top, matching pants and a pink fanny pack, delivers the final pre-game pep talk to La Racaille players who surround her near their bench.

“Whose game is this?” she shouts.

“Our game!” the players yell back in unison.

“Whose house is this?”

“Our house!”

“Whose track is this?”

“Our track!”

“Whose team is this?”

“Our team!”

It’s obvious the players respect her, and why not? At age 30, she’s among the elite of the Montreal Roller Derby, a six-year veteran originally from the small northwestern British Columbia town of Terrace, with a population of about 11,000, which sits on the Skeena River amid thick forest and high mountains. It’s a mecca for outdoor enthusiasts. Individuals there tend to be rugged. Why should it be any different with Bone Machine? Her roller derby profile lists her “likes” as home-made bear sausage and mud-bogging. She says that her tryout with the New Skids was “love at first booty shake.” Her dislikes? “The system.”

Everything about roller derby smacks of alternative lifestyle, even the names, such as Bone Machine — the title of a love song on the 1988 Surfer Rosa album recorded by the Boston-based rock band Pixies, which the late musician Kurt Cobain cited as the main influence in forming his grunge band Nirvana. The lyrics of Bone Machine read in part:

I think you’re pretty. You make me hard. Your island skin looks Mexican. Our love is rice and beans and horses lard. Your bones got a little machine. You’re the Bone Machine.

Bone Machine is also the title of a Grammy Award-winning primal rock album recorded in 1992 by Tom Waites, featuring a healthy dose of percussion and guitar. It won its Grammy in the category of Best Alternative Album and was described by music critic Steve Huey as Waites’ “most cohesive album…a morbid, sinister nightmare….”

And let us not forget Bone Machine, an ex-cop who was one of the villains in RoboCop: Prime Directives, a television mini-series released in 2000 based on the movie RoboCop.

With 20:57 left in the first 30-minute half and Les Contrabanditas leading 12-11, I become fixated trying to make out a tattoo on Bone Machine’s left triceps as she stands in front of the bench, hands on hips, exhorting her players to, “Get to the front earlier!” Those coming off the track for a respite are regaled: “Good job guys!”

“It’s a bee tattoo,” I shout out to no one in particular, with the sense of epiphany usually reserved for ground-breaking research. My photographer, Karen, stares at me as though I am either missing the game or my mind in my obsession with Bone Machine details. “Not to worry,” I mutter to myself taking another swig of beer while I scribble a note that the coach is wearing large gold hoop earrings. “I’m getting the hang of this game.”

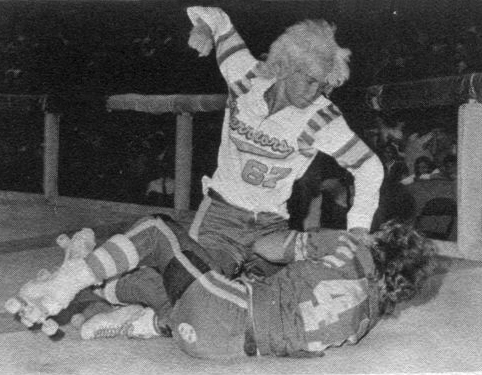

The rough ‘old days’Of course, it’s nothing as violent as the scripted roller derby played on a banked track that I remember watching on television in the 60s and 70s, featuring men and women roughhousing for such teams as the San Francisco Bay Bombers and the New York Chiefs of the National Roller Derby League (NRDL).

Roller-skating first came into the public consciousness in the 1880s as multi-day, endurance races. By the mid-1930s, an entrepreneurial American film publicist named Leo Seltzer was encouraged by sports writer Damon Runyan to turn the roller-skating marathons into a competitive, contact sport.

The idea succeeded. In 1940 more than 5 million spectators watched professional roller derby in some 50 U.S. cities. However, over the ensuing decades, it became increasingly more entertainment than sport, featuring player theatrics and pre-determined results. In 1949, Seltzer formed the NRDL, and although live gates were declining, newly discovered television audiences in the 1950s picked up the slack, reaching a peak of about 15 million viewers weekly on U.S. network television by 1969.

In 1973, high overhead, including skyrocketing oil and gas prices due to the Yom Kippur War between Israel and its Arab neighbours, persuaded Seltzer to shut down the league. American author and cultural historian Paul Fussell, who passed away on May 23, 2012 at age 88, wrote in 1983 that the closure was due to the deteriorating finances of the fan base which lacked the purchasing power to support the sport’s television sponsors.

There were efforts to revive the sport in the 70s, 80s and 90s, but it never regained popularity until the women of the WFTDA re-launched it in 2004 as a serious sport played on a flat track, with players donning derby names and colorful uniforms as the only vestige of its earlier incarnation as pure entertainment.

Some capitalists might be tempted to view this grass-roots revival as a potential cash cow if it could be ramped up and organized by them into a professional sport. But they would do well to remember the DIY credo of the “amateurs” who now run it without “bosses” and who are cynical about big business, which includes some professional sports with their spoiled millionaire athletes and domineering billionaire owners divvying up revenue from exorbitant ticket prices and rich television contracts. Already a serious, competitive sport open to athletes ranging from great to average, women’s flat track roller derby offers affordable, exciting entertainment for people on a budget. There are no BMWs, Mercedes or Porsches in their parking lots.

The Chicago-based Derby News Network is a non-profit, mostly volunteer digital media organization which uses the Internet as the clearinghouse for news and video broadcasts of both men’s and women’s flat track roller derby. It reinforces this DIY message on its Mission & Vision page, calling for the sport to maintain its “independent, quirky, cheeky, by skater/for skater inclusive identity.”

It goes on to say:

We believe the organic, DIY growth mode of modern roller derby has no limit. We think the same is true for derby media. Let’s sell out every bout, but let’s never sell out. We’ve built DNN on the same principles that guide the sport’s community: do-it-yourself, collaborative, passion-driven, crowd-sourced….

In Canada, Canuck Derby TV works in collaboration with DNN to disseminate video broadcasts, news and results for men’s and women’s flat track roller derby.

Canuck Derby TV weren’t the only ones shooting video of Montreal Roller Derby at the games I covered. Award-winning filmmakers Maya Gallus and Justine Pimlott of Toronto-based Red Queen Productions are documenting this DIY grassroots sport and its unique subculture for Global TV in Canada, as well as for international broadcast and film festivals. Hot Rollers (working title) follows the New Skids On The Block as they challenge the reigning stars of roller derby at the fall 2012 WFTDA Championships.

— Partial excerpt, Mission Statement, Derby News Network

Gallus told me in an interview by email in early September 2012 that Hot Rollers will introduce viewers to some of the extraordinary women in the world of roller derby, including New York's legendary Gotham Girls Roller Derby and London Rollergirls, as well as the people working behind the scenes to take this increasingly popular sport to another level. “Hot Rollers will present powerful women on a quest to test the limits of their own strength, overturning conventional notions of femininity and forging a new image: Woman as Gladiator,” Gallus said.

So as multiple cameras recorded the skaters rolling around the track on this sweltering Saturday night in July, hundreds of raucous, working-class fans — many in tank tops and shorts — soaked up the action. A couple were blowing their foghorns as they stood on the concrete floor in what is known as the “suicide section”10 feet from the track.

With 14:14 left in the first period and La Racaille trailing 45-16, Bone Machine calls a time out to give a pep talk. I’m straining to hear her words, but I can’t catch them because DJs T-Bo and Chris are cranking out on the PA the Nancy Sinatra classic, These Boots Are Made for Walkin’. As Nancy’s last notes echo through the arena, I hear Bone Machine exhort her charges: “Now play some roller derby!”

Her inspirational message doesn’t change much: by the time the 15-minute halftime rolls around, Les Contabanditas are leading 86-43. Everyone is off to their dressing rooms — the players and the volunteer officials, including all seven referees and 15 non-skating officials who are needed to keep track of a fast-paced game where each team fields five players at a time — a jammer and four blockers, including the blocker near the front of the pack called the “pivot”, who is the last line of defense and moves to help out wherever she is needed while keeping the pack together.

Patrik passes by, pearls of wisdom slipping between his ruby lips, glowing predictions to the effect that La Racaille has a history of staging second period comebacks. With a couple of minutes to go before the halftime show, Patrik gives me another primer on the salient rules of the game:

Each team designates one scoring player, known as the "jammer". Points can be scored only during "jams”, which are plays lasting up to two minutes which start when a jammer passes all the five players on the opposing team. Once this “lead” jammer passes the pack for the first time, a point is awarded to her team every time she passes an opposing player thereafter. The jam ends when either the referee blows the whistle or the lead jammer puts her hands on her hips.

Whoops, tutorial is over. Time for another brew and Dance Animal, the halftime entertainment which bills itself as “The World’s Only Comedy Dance Tribe.” The PA is belting out the 1993 hit, Holding Out For A Hero from the Bonnie Tyler album titled The Best, while Robin Henderson’s troupe, composed of four men and four women dressed in pink and black with pink headbands, dance their booties off.

Dance to the beatLike many connected with women’s roller derby in Montreal, the Ottawa-born Henderson is a transplant, arriving from London, England in 2004 to work as a choreographer and director. Under her direction, Dance Animal has won numerous citations and awards including the Just For Laughs “Best Comedy Award” in 2009 and the Cirque du Soleil “Best Original Creation” award in 2010.

The crowd is roaring its approval of the dance moves and music, the stands reverberating with the stamping of feet and the clapping of hands to the beat and lyrics of the song:

…I need a hero

I'm holding out for a hero 'til the end of the night

He's gotta be strong

And he's gotta be fast

And he's gotta be fresh from the fight…

Robin does not play the sport herself, but is a big fan of what she describes as the players’ “impressive” athleticism. She’s also thrives on the hyped-up roller derby crowd. “We love when the crowd starts to cheer and dance with us,” she told me. “The more energy the audience gives, the more we give back. Our shows are styled after rock concerts. We’re performers!”

Patrik is grooving to the beat of Dance Animal, tapping his left high-heeled bootie while his fingertips lightly caress his swaying hips. Two passing male photographers hug him. The 15-minute intermission wraps up with another lively dance rendition, this time to the beat of Footloose, the 1984 No. 1 release by American singer-songwriter Kenny Loggins for the movie of the same name.

Unfortunately for La Racaille, the high-energy halftime performance does not extend to their second half play, and they end up losing the match 163-94. In a show of good sportsmanship, a trademark of women’s roller derby, the opposing players pass one other in single file, slapping hands to the applause of spectators.

The two teams are slated to meet again in the championship game two weeks later. Sneaky Devil assures me the results will be different next time because her team won’t be playing their rookies, as it had this evening in an effort to give them experience.

It’s only 8 p.m. when the game ends. The second match of this double-header is about to begin, offering the best of Montreal Roller Derby — its all-star team, the New Skids On The Block, taking on the New Hampshire all-star team called Skate Free or Die.

The N.H. team has its own contingent of fans who made the three-hour drive to watch their team in action as they sit in folding chairs swilling beer in the suicide section of the floor, also known as the “smash section”.

Stars shine brightDJs T-Bo and Chris play the N.H. theme song Living Dead Girl by heavy metal musician Rob Zombie as the American players are introduced. The Montreal team skates out to the cheers of the crowd and the lyrics from Sexy and You Know It by the Australian hip-hop band Justice Crew.

This team is the backbone of Montreal Roller Derby; not only are they the best players in Canada, they are also heavily involved in organizing the league as a business, training and coaching the various teams, such as Bone Machine’s role with La Racaille.

None has been more influential than Georgia W. Tush, who founded the league in 2006 and outfits the players with equipment from her shop called Neon Skates. The boots she sells range from $229 to $399 for the Riedell 965, described as having “a hand sorted full grain leather upper, beige suede microfiber foam backed lining, and a padded collar and tongue.” It is hand-made in the U.S.A. with a “HF-5 heat moldable reinforcement on the outside quarter right boot.” When roller derby gals shop for boots, they’re not looking for style, as much as comfort and performance.

Tush moved to Montreal from her native Thunder Bay, Ontario in 2004 to study political science and history at Concordia University. By 2006, she had caught the roller derby bug, learning of its launch two years earlier in the U.S. and subsequently in Toronto, Vancouver and Hamilton. Why not start something in Montreal?

When she was young, Tush roller-skated, skied, swam, cycled, played hockey and volleyball. So it seemed like a natural progression of her love for sports to organize a group of 14 roller derby enthusiasts, which eventually grew into Montreal Roller Derby with her as its first president.

They held their first meeting in 2006 in the oldest alternative rock and dance venue in Montreal, called Les Foufounes Électriques, which translates into “Electric Ass”. So it’s easy to see the connection between the venue name and her roller derby name “Tush”, which is English slang originating with the Yiddish word “tokhes”, meaning buttocks.

By 2010 she had figured out that her political science and history majors weren’t going to be nearly as much fun or as lucrative as a business selling roller derby equipment, so she opened Neon Skates as a supplier of skates, accessories and apparel. Most of her clients are from Montreal, but she also sells to players in the Maritimes and Ontario.

Of course, being a member of the New Skids, one of the top 20 teams in the world, is good for business. New players like rubbing shoulders with an all-star who played for Team Canada at the first biennial World Cup, held in Toronto in December 2011. She broke her collarbone in that tournament in a winning effort against Team England, before losing the final against Team U.S.A.

When I look for wheels at Neon Skates, I find brand names like Reckless, Radar, Atom and the extra narrow Heartless, which has an illustration of a woman’s red lips on the wheel itself next to a partial face showing eyes and eyebrows.

Wheels, I discover, can be made of hollow core nylon for grip and speed, solid core for constant grip and traction or hollow, lightweight core alloy for maximum speed. They’re judged by a performance matrix for various skating styles and surface requirements. The mathematical equations remind me of a high school algebra class. Aficionados use “durometers” to measure the hardness of the cured rubber on the wheels, which determines, in part, how they grip the surface.

So like the game itself, which involves strategy and tactics, there is much to know about equipment. Regardless of outerwear and tactics, it’s obvious that the core of the sport is predicated on athletic prowess and toughness.

Apocalipstick performance

Once the second game begins, one player in particular, Apocalipstick, No. 2000 for the New Skids, catches my eye with her elegance, dexterity and speed. She is wearing the two stars on her helmet, indicating she is the designated jammer whose objective is to score points by passing opposing players. On this night, she is virtually unstoppable, deking in one direction and accelerating opposite, gliding by her opponents as though they’re skating on sand. With 23:30 left in the first period, the New Skids lead Skate Free or Die by 53-1. Of the 53 points, Apocalipstick has scored 27!

Those who remember the Amazonian women who played old-fashioned roller derby on the banked tracks in the 60s and 70s might be surprised to learn that today’s players can actually be petite and look very feminine. With her helmet on, I can’t garner a full view of Apocalipstick, but I do notice that she is svelte. League statistics list her as 5 foot, 3 inches. A team profile photo of her wearing sunglasses without the helmet show a woman with long dark hair tied back, with a pearl earring in each lobe.

Based on her profile “likes” of “looking good!” and “dislikes” of “wearing a helmet on a good hair day!”, I conclude that roller derby has not bruised her feminine vanity.

She shows off her cat sharp reflexes, constantly readjusting her nimble, rolling feet on the concrete track as she dips and doodles between opposing players. I later learn that she had a long career as a figure skater before trading in her blades for quads. Her favorite expression, “No nuts all glory,” says it all about women’s roller derby.

It’s a sport where a smaller, agile female physique with good skating ability can excel. The Guinness World Records cites Debbie Rice, a.k.a. BarbieBont of the Tampa Tantrums, a WFTDA all-star travel team, as the fastest woman on skates at the equivalent of 61 m.p.h.

The Rev, who coaches the New Skids and plays for the Mont-Royals team in a men’s league, acknowledges that women, rather than men, dominate the sport. Why? “These women are real athletes,” he told me. “They’ve more than made the sport their own. They’ve hoisted it above their heads.”

The women’s game is robust, but fights are rare to non-existent. Blocks on the sides, chest and hips are legal, as players try to push their opponents outside or maneuver them inside the track. Swinging the elbows or forearms to deliver a hit is illegal, as are checks from behind, hits to the head, as well as tripping, kicking, slapping and choking. Violators are usually banished to the penalty box for one minute or sometimes for a double if they have committed more than one infraction. They can be expelled from the game for an act of extreme violence, but that rarely happens.

There are numerous injuries to fingers, arms and legs, but on this night most require only superficial treatment, such as ice and tape, administered by rink-side physiotherapists Tara McAleer and Véronique Rondeau of Concordia University, who are paid by the league.

At halftime, the score is 197-8. Despite encouragement from their fans in the Smash Section waving a “Go New Hampshire” placard, Skate Free or Die seems to be doing a little of both, still skating hard but barely alive when its jammer and co-captain Moxie Moonwalk scores 4 points with 7:38 left in the game making the score 332-17.

“Hustle, hit, never quit,” the N.H. players are chanting. Moxie Moonwalk tries to no avail to get her teammates on the bench to do the “wave”, but they have little energy left near the end of this grueling match, which ends 354-30 in favour of the New Skids.

When the final whistle blows, I am once again struck by the sportsmanship and positive attitudes, as players from both teams hug and slap hands to the cheers of the crowd. N. Raging Grace, the New Hampshire team’s co-captain who works in the medical insurance field in Whitman, Massachusetts, 25 miles south of Boston, says the comradeship is one of the reasons that women’s roller derby is growing so quickly.

When her friends find out she is playing roller derby, she says their reaction is one of disbelief that roller derby is back. “They think it’s cool and different. Those who know, come to see me play.” Like N. Raging Grace, most players in leagues around the world hold white collar jobs by day, cross-training and attending roller derby practices on weeknights, with games scheduled on weekends.

Moxie Moonwalk, who works for an investment bank in Boston, tells me that her team performed to about 90 percent of its capacity, but couldn’t handle the “tight game” and the New Skids’ high level of skating. “It’s a learning experience,” she said of the loss. “They’re a great team. We beat the snot out of each other, but now we’ll go to the after-party and have drinks together.”

Every after-party is held a couple of blocks away at the Royal Phoenix Bar, co-owned by one of the league stars, Smack Daddy, who plays for the New Skids and coaches Les Filles du Roi. Smack Daddy was still out of action as of August 2012 due to a spiral fracture to her right tibia and fibula suffered during practice in March 2012. It took a plate and 13 screws to repair, but the MVP of the first Roller Derby World Cup held in Toronto in December 2011 was healing well and planning her comeback.

Smack Daddy grew up in the affluent municipality of Beaconsfield, just west of Montreal, in a family that loved to play hockey and watch it. She studied sociology at Concordia University, specializing in issues of gender and sexuality.

Her roller derby bio says she is known as “Daddy” because she is very loyal and protects teammates as though they are her family and “Smack” because she knows how to give a smackdown to opponents when necessary. Like most of the other roller derby gals, she was introduced to the sport by a friend, Beater Pan-Tease, who plays for Les Filles du Roi.

Sports and sexualityThe 5 foot, 8 inch Smack Daddy, who rocks a Mohawk, tells me she was born athletic and lesbian, but had to deal with a homophobic West Island community where she grew up. She came out of the closet towards the end of her undergraduate studies at Concordia, where she also played soccer. She went on to New York University for a master’s degree in visual arts.

She would have loved to stay in New York City and play for the Gotham Girls Roller Derby, considered the No. 1 league in the world. But Smack Daddy, who gives the impression of following her heart when making lifestyle decisions, says she did not fall in love in New York and ended up returning to Montreal, which is also known for its hot night life.

These days, she celebrates rather than hides her sexuality, telling me that many lesbians play in the Montreal Roller Derby, but the majority of participants are straight. Between 30 and 40 percent of the New Skids are lesbian, she said, but nobody cares about a player’s sexual orientation; they’re all passionate about the game.

There is hope among roller derby players and organizers that their sport can one day be included in the Olympics, which New York Times op-ed columnist Frank Bruni described in a July 21, 2012 article as the arena where female athletes are liberated from “the straitjackets of convention and conformity,” allowing them to be fully recognized as the athletic equals of men. He pointed out that the 2012 U.S. Olympic team was, for the first time, composed of more women than men — 269 compared with 261.

The Olympics “acknowledge that female glory takes many forms,” Bruni wrote. “That’s important not because of any vague, reflexive political correctness, but because saluting women’s athletic achievements encourages their athletic pursuits, which can impart invaluable life lessons about teamwork, tenacity, sacrifice, conviction.”

Smack Daddy says it “kills” her when she sees bikini-clad babes being treated as serious athletes competing in beach volleyball at the Summer Games every four years. But she knows that one of the major impediments blocking inclusion of women’s roller derby as an Olympic sport is the issue of transgender players — that is players who were born men but are now living and playing as women.

It is a touchy subject for all the women’s roller derby leagues. The issue is at what point transgender individuals are to be considered women. In its constitution, which is an evolving document, the Montreal Roller Derby follows the lead of the WFTDA in specifying that transgendered persons who wish to play in their league do not have to undergo sex reassignment surgery, but they must prove that they have been living full-time as women and have had female hormone levels for at least one year.

Aside from transgender issues, the subject of “alternate femininities” has drawn the attention of several academics, including Natalie Marie Peluso of the University of Connecticut who wrote a dissertation which became a 368-page book titled High Heels and Fast Wheels: Alternative Femininities in Neo-Burlesque and Flat-Track Roller Derby, published in January 2010. In an abstract, she argues that flat track roller derby “offers women performative opportunities to transgress cultural norms regarding gender and sexual identities, and the appearance and performance of the physical body.” She says her study also examines whether “derby skaters view what they do as oppositional or political.”

Nancy J. Finley of the University of Alabama wrote an academic paper titled, Skating Femininity: Gender Maneuvering in Women’s Roller Derby, published in the Journal of Contemporary Ethnography in August 2010. The abstract from her paper reads in part: “…alternative femininities in the image of a derby girl…can be important in challenging hegemonic gender relations….the athletes feminize their participation in an aggressive sport through resistance, adaptation, mockery, and parody of hegemonic femininity….”

In 2008, Carolyn E. Storms of the University of Buffalo wrote in Vol. 3 of The New York Sociologist a paper titled, There’s No Sorry in Roller Derby. In the introduction, Storms wrote:

The purpose of this ethnographic study is to explore challenges and issues of identity, such as questions regarding the femininity of women who engage in full contact competitive athletics. The nature of the research question is to discover what changes in identity occur for women who participate in physically aggressive sports such as roller derby.

So while academics have twisted their knickers in a knot trying to decipher the myriad implications of women’s roller derby, Smack Daddy seems less concerned with analysis and more intent on living for the moment, as personified by Cyndi Lauper’s 1983 smash single, Girls Just Want To Have Fun. The partial lyrics:

My mother says, When you gonna live your life right?

My father yells, Whatcha gonna do with your life?

The refrain: Oh girls just wanna have fun!

That suits to a T the attitude of Smack Daddy, who describes herself as “a little bit of a charmer” in her younger party days. Lately, the derby girls have toned down their wild after-parties that used to devolve into alcohol-fueled, topless orgies of passion, raging until 3 a.m. amid the rotating strobe lights and humid, perfumed air of the Royal Phoenix.

Oh, Derby Baby!The league is getting more serious these days with its emphasis on dedicated athletes, training and diet, rather than its earlier party days when players could be spotted sipping beers on the bench during a game. “Now it’s 90 percent sport and 10 percent entertainment,” Smack Daddy tells me, adding that she is making connections with other sports leagues, such as Team Canada’s women’s hockey team, to establish training protocols.

If you want some perspective on the international scope and popularity of women’s flat track roller derby, check out the 2012 documentary titled Derby Baby! produced by Ron Patrick and directed by Dave Wruck and Robin Bond. Between June and fall 2012, there were close to 200 screenings scheduled in cities around the world, with revenues available as fund-raisers for women’s flat track roller derby leagues.

Ron told me in a telephone interview from Denver in early September that DVDs and Blu-rays were to be sold online at derbybabythefilm.com, with a sizeable percentage of the gross revenues going to the international charity Plan International, which promotes children’s rights and fights children’s poverty in 50 developing countries in Africa, Asia and the Americas.

Dave and Robin, Emmy Award-winning filmmakers, travelled around the world on their own nickel interviewing players and filming action in various leagues in a quest to understand what is attracting tens of thousands of women to the sport. Over a period of two years, two months, they captured the drama, passion, friendships and allure of the sport.

In sync with the sport’s DIY ethos, they paid out of pocket for 88 percent of production costs, with only the 12 percent needed for sound finishing and colour correction coming from corporate sponsors. In an effort to get the film distributed internationally via theatres, DVDs and Blu-rays, they collected $80,763 in one month from 734 donors on kickstarter.com, a crowd-funding, U.S. website which raises money for creative projects. Their original goal was to raise $30,000.

They’ve posted a spunky trailer for their documentary on YouTube which describes women’s flat track roller derby as “the fastest growing, most misunderstood sport in the world”, concluding that it is “an international phenomenon at the tipping point of stardom.”

The documentary is narrated by actress/musician Juliette Lewis, whom the filmmakers met in Toronto in December 2011 where they shot footage of the first Roller Derby World Cup, won by undefeated Team U.S.A. which hammered Team Canada 336-33 in the final.

It may be hard to believe but those 33 points scored by second-place Team Canada represented the most points scored against Team U.S.A., described by Team Canada co-captain Brim Stone, who hails from Haliburton, Ontario, as “the fiercest competitors….”

One of those fierce Team U.S.A. competitors is Suzy Hotrod, a 32-year-old jammer for the all-star Queens of Pain of the Gotham Girls Roller Derby league in New York and one of the best skaters in the world, which is quite an accomplishment considering she couldn’t skate when she started playing the game eight years ago.

If the name or muscular body ring a bell, it may be that you saw a photo of her as one of the featured athletes in the 2011 Body Issue of ESPN magazine. The image of her 5 foot, 7 inch body airborne in the buff, wearing only skates and tattoos, was reproduced on the WFTDA’s website in November 2011, a month before she skated in Toronto for Team U.S.A.

She says that her signature move is “hopping and jumping all over the place,” describing her jamming style as “just on the edge of out of control.” She calls herself “a fighter” who will go down swinging, if need be. And if her buttocks look tight in that ESPN photo, it’s because they are! Her team profile states: “My leaguemate told me that getting hit with my ass hurt like being beaten with a rolling pin. I blushed.”

Her star power is such that she was transformed into a video character in Jam City Rollergirls, the video game developed by Frozen Codebase, with a lot of input from Suzy Hotrod. Roller derby has changed her life and body, she says, explaining that she played guitar in a punk band and hadn’t exercised in four years when she first started skating in 2004.

With colourful, talented athletes like her, Smack Daddy and 258 others on the 13 international teams competing, is it any wonder that the four-day competition in Toronto, organized by L.A.-based Blood & Thunder Magazine, was sold out one week before it began on December 1, 2011, with tickets for the 1,500 seats ranging between $20 and $125.

Team England finished third, followed by Australia, Finland, Sweden, France, New Zealand, Germany, Ireland, Scotland, Brazil and Argentina. Derby Baby! producer Ron Patrick said that substantial footage was shot at the Roller Derby World Cup in Toronto, including an interview with Suzy Hotrod.

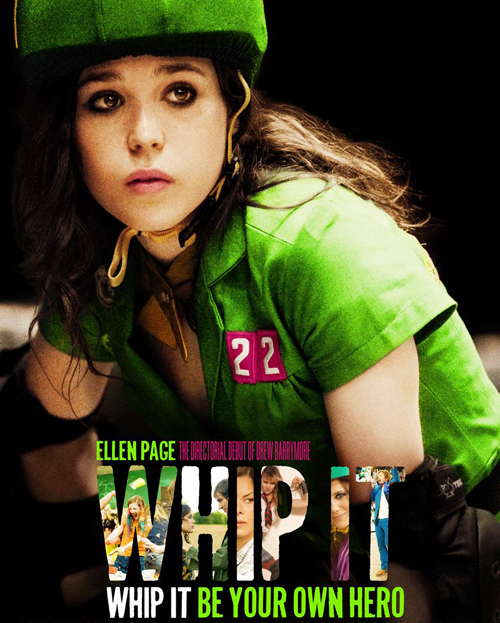

The documentary’s narrator Juliette Lewis also starred in the 2009 Hollywood roller derby movie Whip It, directed by and starring Drew Barrymore, along with Canadian actress Ellen Page and Kristen Wiig. Despite some inaccurate depictions, such as spectacular but illegal hits and a banked track rather than a flat track, that movie has helped put the sport on the public’s radar.

In Whip It, Page plays an indie-rock-loving misfit in Bodeen, Texas who deals with her small-town misery by joining a roller derby league in nearby Austin. The movie poster shows Page wearing a green helmet and a matching uniform, with the No. 222. The subhead on the poster says: “Be Your Own Hero”.

Be your own heroThat could well be the motto for Smack Daddy, who lives and breathes roller derby, spending about 20 hours a week on the sport, including three to four practices. Her bar, which opened in June 2011, is advertised as a “joint for everyone who likes a stiff drink, a wild dance party, homemade fries, 5 à 7 time with friends and a perfectly stylish and unpretentious vibe.”

Smack Daddy, who turned 33 in 2012 but whose derby profile describes her as “somewhere between a kid and an adult”, says the idea of opening a bar grew out of her involvement with Montreal Roller Derby because she and other players wanted a clubhouse where all players and patrons — straight or gay — would feel welcome. Although many think of the Royal Phoenix as primarily lesbian, she encourages a mixed clientele which reflects the makeup of women’s roller derby.

The comradeship engendered at practices before games and at after-parties is an integral part of the roller derby experience. It is the perfect antidote to what scientists and medical authorities are beginning to recognize as a serious problem of social isolation and diminishing interpersonal relationships caused by a digital culture where young people are more adept dealing with computers than with other living beings.

I make a note to visit her bar after the championship game in two weeks time, which turns out to be another sweltering Saturday night at the beginning of August. As during the double-header two weeks earlier, Smack Daddy is on the floor, cheering on the players from La Racaille and Les Contrabanditas, who by halftime are again leading, this time 71-41.

Dressed in a green tank top, white shorts and wearing a gold link chain around her neck, Smack Daddy is a vibrant, animated presence, especially during the halftime show which features two males wrestlers in a temporary ring stomping and body slamming each other. Clutching a beer in one hand, she alternately thrusts her arms in the air with clenched fists or gives a thumbs down when the action in the ring does not meet her expectations.

A perfectly bilingual French-Canadian, she’s high profile in Montreal’s lesbian community, hosting events in the annual parade every August for the LGBT community (lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender). She describes herself as “a visual artist working in performance, intervention, video and photography”, having appeared in a solo stage show in 2009 called “Peur Laine”, which broke down Quebec cultural stereotypes while telling her story as a French-Canadian lesbian. She also starred in “Hot Hot Gossip”, a 2008 multimedia lesbian soap opera. In the past, she worked as a DJ for Montreal’s lesbian Meow Mix parties and managed Faggity Ass Fridays, a monthly party for queers.

She describes her current role as a roller derby player and a bar owner as her “dream job”. As pertains to the sport, she tells me that it is still openly debated as to what came first: lesbian athletes with elevated testosterone levels or flat track roller derby which attracted such female athletes. Whatever the case, it’s really not a lesbian sport at this point she said. “We have many married straight girls. It’s a huge mix. Roller derby is the epitome of the queer community. It’s about breaking down stereotypes and being accepted.”

As the second period of the championship game is about to begin, Smack Daddy removes her running shoes, dancing on the concrete floor in her white socks to the tune of Tom Petty’s 1989 single, I Won’t Back Down. The lyrics seems appropriate to her credo and lifestyle:

Well I know what’s right, I got just one life

In a world that keeps on pushin’ me around

But I’ll stand my ground and I won’t back down

With 24 minutes left in the game, La Racaille closes the gap to 71-65 and 30 seconds later takes the lead for the first time 75-71. But Les Contrabanditas storm back, winning 184-130, retaining their title as league champions.

Party on amigo!Like many of the fans, I head off to the Royal Phoenix Bar two blocks away, thinking I might run into Sneaky Devil and congratulate her on a hard-fought match. When I arrive at the bar 15 minutes later at 10:40 p.m., patrons and fans have already started sauntering in.

Strobe lights and techno music greet me. There is a large dance floor and one unisex bathroom with sinks on the right, urinals on the left with a few stalls a few feet beyond that. Cheap drinks entice — three shots of vodka or whiskey for $10, two Canadian beers for $7 or the premium Mexican beer, Sol, for $6. I buy two bottles of Sol, one for myself and one for my photographer, Karen.

Most of the patrons are women, but there are numerous men: many tank tops and lots of love. Two women next to me embrace, exchanging a deep kiss. Karen and I carry our beers to a standup, elevated table where two men in their 20s are in deep conversation as they nurse their drinks. One of them, from Toronto, is wearing a black t-shirt with blue, yellow and pink lettering which reads: “Fuck You + Your Toys”. The man facing him is a local and seems to be enjoying the conversation until he is interrupted by a third fellow, this one French-speaking, who brushes his hand discreetly across his buttocks. Allo Montréal!

At 10:55 p.m. Smack Daddy arrives, a black top covering her roller derby sweater. She walks behind the bar, exchanging words with the DJs in the control booth. Suddenly the music switches to the disco beat of the 70s and everyone is on the dance floor. Black ceiling-to-floor curtains are drawn across all the windows and candle warmers are lit on the tables.

She’s “da man”, the good time gal spreading joy. A vaunted after-party is gearing up and promises to be everything as advertised. All comers are welcome, enjoying the laissez-faire nocturnal ambience. But Sneaky Devil is nowhere to be found.

I later discover that between 30 and 40 members of the two teams who played in the championship celebrated into the wee hours of the morning in the green space near the arena parking lot, imbibing cold beer and champagne. They gabbed in English and French about the game, the season, vacations, hopes and dreams.

Sneaky Devil’s mother, Marjorie, recalls for me in a telephone interview that her daughter was “a quiet kid who didn’t say much and didn’t open up” as a youngster in Assiniboia, Saskatchewan, but adds that “she had a mind of her own and knew what she wanted.”

Now that shy girl has evolved into a roller derby diehard playing the game with gusto and then kicking back with what she calls her “little diverse family” of skaters. On the track, it’s game on. Off, it’s a lifestyle emphasizing freedom of action and expression, which was perhaps a factor in her recent decision to return to college to study 3D animation.

“The flat track is like home to this flatlander,” Sneaky Devil wrote in her team bio. When asked whether she would ever move back to Saskatchewan, the girl with the sugar skull tattoo replies without hesitation: “I can’t imagine living in a small town any time soon. Especially one without roller derby.”