Updated: date

Published: May 17, 2017

Trumponomics and trade: the future of NAFTA

Analysis by SUSY ABBONDI

Writing from Montreal

Editor’s Note: BestStory.ca welcomes its newest contributor, Susy Abbondi, a financial analyst and portfolio manager whose interest in economic issues and trends dates back to coffee house chats with her grandfather during her teenage years. Susy's biography can be found here.

No campaign promise resonated more with his supporters – and perhaps even thrust Donald Trump to presidential victory on November 8, 2016 – than his anti-free trade stance and eagerness to overhaul U.S. trade relations.

Punctuated by his “America First” slogan, one of the president’s top priorities is to renegotiate – and perhaps dismantle – international trade pacts such as the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which he has repeatedly referred to as “the worst trade deal in history”.

Trump blames unfair trade – with Mexico and China in particular – for the loss of millions of factory jobs, and, not surprisingly, has repeatedly threatened to impose hefty tariffs as high as 45 percent on their imported products.

Although these promises may very well be what secured his victory, his plan for restoring American jobs and reducing the trade deficit are oversimplified, at best. Nevertheless, American voters have come to view these trade agreements as a dirty symbol of globalization, eating away at their domestic job market.

Promises made on the campaign stump – some controversial and potentially damaging – will inevitably be limited by economic reality. Aside from a wall along the 2,000-mile southern border, if Trump follows through on his protectionist pledges, they could not only curb America’s global engagement and demolish decades of progress, but also capsize deeply-established policies on trade.

Just as anticipated, U.S. trade agreements were one of the first economic casualties of the election. On January 23, 2017 an executive order was signed for America to pull out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), an ambitious trade agreement which proposed to bring together 12 countries (including Canada), accounting for approximately 40 percent of global economic output. At the same time, Trump also reconfirmed his intentions to renegotiate NAFTA, which since its implementation on January 1, 1994 has removed tariffs on products and services exchanged among the U.S., Canada and Mexico.

As the president attempts to rewrite history, America could be facing the real threat of economically destructive trade wars, especially taking into account that presidents have a large measure of authority over trade policy, even without congressional approval.

What is at stake in terms of trade?

No other neighbors are more fundamentally linked than Canada and the United States. It is not just a matter of geography, but of common interests and values that connect us beyond our multi-layered economic ties. One of the best metaphors to describe the relationship between Canada and the U.S. came from then-prime minister Pierre Trudeau, during a 1969 state dinner in Washington. He expressed that being a neighbor to the U.S was like sleeping with an elephant – no matter how friendly or even-tempered the beast may be, his mammoth stature means that Canada is affected by even the smallest twitch or grunt.

Canada has always had friendly relations with the elephant to the south, and liberal economic ties that superseded those of NAFTA. The U.S. and Canada had a free trade agreement in place since 1988, but as NAFTA negotiations began in 1991, the goal became to integrate these two highly developed economies with that of emerging Mexico. The first time in history that rich countries and a poor country did away with trade barriers in order to compete on even terms.

The objective was to facilitate economic growth by easing the flow of goods between the three countries. Not only was Mexico seen as a lower cost investment location, but it also had the potential to be a promising new market for exports. While in Mexico, it was viewed as an opportunity to modernize the economy and give the population less reason to flee across the northern border – a win-win for all.

When NAFTA finally came into force in 1994, not only did it gradually eliminate tariffs and restrictions on trade, but it also brought with it protection for foreign investors, as well as a reduction in the overall cost of commerce. More importantly, the agreement enhanced the competitiveness of both American and Canadian companies. It was the first agreement of its kind, and to this day encompasses the world’s largest free trading bloc in terms of GDP.

Prior to the advent of free trade agreements, imported goods were taxed, while protected domestically produced goods were made at the expense of consumers, to whom the added cost was simply passed down. Economic theory tells us that higher tariffs lead to more costly goods and generally less trade. Free-trade agreements turn this equation on its head. When you remove the tariffs, not only do you lower costs for consumers, but you create a strong incentive to trade, which leads to higher productivity and increased GDP.

Aside from the general discontent of some American voters and President Trump, there are many proponents of NAFTA, and understandably so. According to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, since the agreement entered into force, trade with Canada and Mexico has nearly quadrupled, reaching over $1.3 trillion in 2014. To put it in perspective, this means that the U.S. trades more than $3.6 billion in goods and services each day with its neighbors, $2 billion of which is with Canada.

Of course, trade is a two way street; Canada and Mexico do their part by buying more than one-third of all U.S. merchandise exports, making them the largest markets in the world for U.S. goods. According to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, Canada with its modest population of 36 million, purchases more from its southern neighbor than does the whole of the European Union with a population of approximately 500 million. In fact, Meredith Lily, former Foreign Affairs and International Trade Adviser to Prime Minister Stephen Harper, wrote in Policy Magazine (Volume 5 – Issue 1, January/February 2017) that 35 U.S. states “list Canada as their number one export destination”. Also interesting to note, Mexico with its population of 125 million, purchased more than $240 billion worth of U.S. merchandise in 2014 – nearly twice the amount America shipped to China, and more than to all of the BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India and China) nations combined.

The upside of NAFTA

Mark Twain once famously said: “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes.” In fact, this is not the first time that we have seen NAFTA come under scrutiny and become a central argument in a presidential electoral campaign. In his bid for president in 1992, independent candidate Ross Perot claimed that the advent of NAFTA would ultimately result in a “giant sucking sound” of American jobs moving south of the border. His contention allowed the billionaire businessman and political outsider to shoot to the top of the polls – sound familiar? But in the end, Democrat Bill Clinton won the election, making NAFTA a reality.

In the four years immediately following the commencement of NAFTA, according to the figures provided by the U.S Chamber of Commerce, U.S. manufacturers added more than 800,000 jobs. This is a stark contrast to the period between 1980 and 1993, prior to the creation of the trading bloc, when the U.S. shed nearly 2 million manufacturing jobs. It is also interesting to note that unemployment during this period averaged 7.1 percent, while during the post-NAFTA period of 1994 to 2007 (up to the point of the financial crisis) it averaged 5.1 percent.

A study by Dr. Joseph Francois and Laura Baughman titled Opening Markets, Creating Jobs: Estimated U.S. Employment Effects of Trade with FTA Partners comprehensively examined 14 U.S. free trade agreements and arrived at some telling results. The 2010 study, commissioned by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, concluded that “trade with Canada and Mexico supports a net total of nearly 14 million U.S. jobs, and of this sum, nearly 5 million U.S. jobs are supported by the increase in trade generated by NAFTA.” The Trade Partnership offers analyses regarding the likely competitive impact of prospective or actual trade policies.

What’s more, a 2014 study by the Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE) called NAFTA at 20: Misleading Charges and Positive Achievements found that those jobs supported by the increase in trade also pay an average salary of 7 to 15 percent more than the jobs which have been displaced by the increase in imports. PIIE is a private, non-partisan, non-profit and avant-garde institution dedicated to the study of economic policy. Their main goal is to create awareness and find solutions to deal with the issues surrounding globalization.

Similarly, as per the website of the Office of the United States Trade Representative, U.S. jobs supported by the export of goods pay 13 to 18 percent more than the U.S. national average.

The NAFTA value chain

Inevitably, the enactment of NAFTA caused supply chains to evolve and production patterns to change. Today, it is common to see sourced raw materials move through stages of production in different countries, and even cross borders multiple times.

Looking at the apparel industry, for example, I think we can all agree that there is almost nothing more American than a classic pair of blue jeans or dungarees. But after cotton bales are gathered in the U.S., nearly 100 percent (as per the U.S. Department of Agriculture) of it is sent to Mexican textile mills to be transformed into apparel. As it turns out, 40 percent of good old American men’s jeans are made in Mexico, according to the U.S. International Trade Administration. Overall, the American Apparel and Footwear Association says that 98 percent of apparel available for purchase in the U.S comes from abroad.

A 2010 paper by the National Bureau of Economic Research titled Give Credit Where Credit is Due: Tracing Value Added in Global Production Chains states that 40 percent of U.S. imports from Mexico originated from American companies operating in that country. The same goes for 25 percent of U.S. imports from Canada. Overall, “these two countries account for 75 percent of all U.S. value added returned from abroad.”

Without NAFTA, these value-added trade transactions could have gone elsewhere – dare I even say China? As a consequence of this increased production integration, Knowledge@Wharton (the business analysis journal of the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania), affirms in an article published in September 2016 and titled NAFTA’s Impact on the U.S. Economy: What Are the Facts states that cross-border investment has also grown. Foreign direct investment in Mexico, for example, has surged from approximately $15 billion prior to the enactment of NAFTA, to over $107.8 billion 20 years later.

The benefits of NAFTA go well beyond manufacturing, as the service and agricultural industries have been big winners, as well. As per the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative, Canada is the leading importer of U.S. agricultural products, just as Canada was the No. 1 supplier of agricultural imports to the U.S. in 2015. U.S. agricultural exports to Mexico have grown from $4.2 billion when NAFTA was first enacted in 1993 to $18 billion in 2015.

Convoluted impact of globalization

Granted, amidst all of this positive data, there is nonetheless a debate to be had about the impact of globalization on middle class wages and inequality. While trade has indisputably contributed to the growth of the economic pie, it has caused its distribution to change – in other words, despite the overall gains, the associated costs have not been spread equally across the population, leaving pockets of desolation in its wake. Clearly, this perceived inequality has left a scar on the American working class that has yet to heal – and which Trump was able to capitalize on. Nonetheless, the growing complexity of today’s economic challenges defy simplistic explanation, and it should be made clear at the onset of this discussion that the argument is a convoluted one. There are numerous factors at play that cannot be easily disentangled from other economic, social and political factors that have also influenced growth.

As stated previously, American manufacturing employment was stable and even grew in the years following the enactment of NAFTA, but generally speaking both backers and critics of the trade pact can agree that there has nonetheless been an overall decrease in U.S. jobs.

Estimates vary widely, ranging from 100,000 to as high as 700,000, but it is incorrect to attribute it all to NAFTA. Other factors cannot be discounted, such as the persistent decline in employment that predated the agreement, or the surge in imports once China became part of the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001. In fact, some would argue that since emerging economies are in fact emerging – by introducing economic reform and greater global integration – much of this would have likely occurred with or without the introduction of U.S. trade pacts.

Unfortunately, the threat of offshoring jobs, whether it be to a NAFTA region or beyond, allowed those manufacturers who decided to keep operating on American soil to drive a harder bargain with wages. But perhaps the biggest culprit in the reduction of blue-collar jobs may very well be automation.

Rise of the Robots

The Peterson Institute for International Economics published a 2014 policy brief titled The U.S. Manufacturing Base: Four Signs of Strength, by Theodore H. Moran and Lindsay Oldenski. The brief explores all U.S. manufacturing multinationals over a 20-year period ending in 2014, with the goal of uncovering the economic effects of broadening their operations beyond domestic borders.

The study examines manufacturing as a share of total employment, showing that in 1960 manufacturing accounted for 28.4 percent of non-farm employment in the U.S. economy, but by 2010 that share had fallen to 8.9 percent, and by 2013 it was down to 8.8 percent. Contrary to popular belief, this shrinkage is not due to a reduction in the U.S. manufacturing base, but rather it is due to an increase in output. As you might imagine, the impact of technological progress has played a huge role. Indeed, we have seen a greater than 60 percent increase in gross manufacturing output between 1987 and 2013, reaching $6 trillion.

Yet, despite the overall reduction in manufacturing jobs, the study arrives at a stunning conclusion: “The creation of jobs by U.S. multinationals abroad and the expansion of sales by U.S. multinational affiliates abroad both lead to more production and employment at home, especially in high value-added areas such as R&D.” So not only do you get efficiency gains and greater specialization, making the U.S. more competitive, but ultimately offshoring jobs results in a net positive effect on domestic investment, employment and sales.

In theory, a developed industrial country – such as the U.S. – adjusts to import competition and technological advancement by moving workers into more advanced industries that can better compete in global markets. Instead, it appears that the U.S. workforce was not nimble in adapting to its increasingly skill-intensive, computerized and service-oriented economy. Perhaps policy makers should have done more to encourage the shift from textiles and toys, to aircrafts and semiconductors. In my judgment, this remains America’s largest challenge in Trump’s mission to bring back American manufacturing jobs.

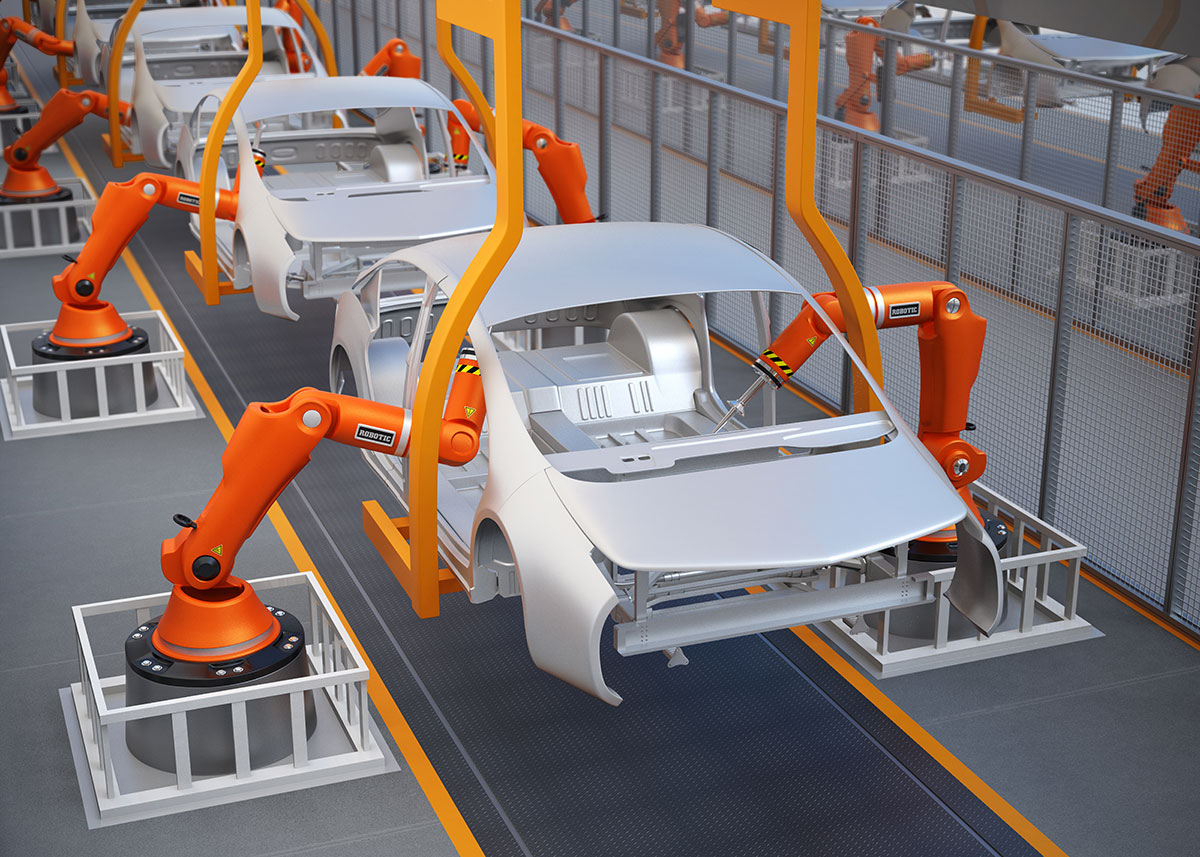

Auto industry and NAFTA

The auto industry is North America’s most prominent manufacturing sector, and although NAFTA propelled it to a new level on interconnectivity, a cross-border connection was established between Canada and the U.S. decades before the 1988 Free Trade Agreement. As noted by The Canadian Encyclopedia, the Canada-U.S. Automotive Products Agreement (commonly known as the Auto Pact), was a “a conditional free-trade agreement signed by Canada and the U.S. in January 1965 to create a single North American market for passenger cars, trucks, buses, tires and automotive parts.”

In the early 1960s the Canadian auto industry was in hardship as a consequence of substantial tariff barriers. Canada had no homegrown auto manufacturer, and there were only a handful of U.S. companies producing vehicles in Canada, almost exclusively for the Canadian market (total Canadian vehicle production in 1960 was just above 379,000).

Canada needed to take action in order to ensure the long-term viability of its auto industry. As per Michael Hart in an excerpt from his book titled The Auto Pact: Forerunner of Free Trade:

As a result of the established pattern of protection, Canadians paid considerably more for cars than did Americans and had to choose from among a narrower range of vehicles. In addition, Canadian autoworkers earned about 30 percent less than their U.S. counterparts. When the costs of the excise tax, the manufacturers’ sales tax and the extra costs of Canada’s less efficient distribution system were added, Canadians often paid as much as 50 percent more than Americans did for the same car. It is little wonder, therefore, that Canadian consumption of vehicles was a third less on a per capita basis than that of Americans. It is also not surprising that by the end of the 1950s Canadians were turning to cheaper imports, principally from the United Kingdom, Germany and Japan.

To address the competitive gap between the two countries, they arrived at a solution with some rather convoluted requirements in order to increase production for export and hopefully achieve economies of scale. Some argue that the Auto Pact only achieved mixed results; it was nonetheless the initial forging of a cooperative effort on trade.

Today, after more than half a century of trade liberalization further pronounced by the introduction of NAFTA, the auto industry has created multi-layered connections between parts suppliers and assembly points which seamlessly span two borders. The tens of thousands of parts that make up any vehicle typically come from multiple producers and different countries, and they often cross borders several times, making up approximately two-thirds of the value of a vehicle. It’s a matter of fact; you can no longer buy an American-made car, just an American-assembled car.

Each car and assembly plant varies in the amount of U.S. content. By taking a look at a new vehicle’s window sticker, we know that a Chevy Silverado pickup assembled in Indiana is made up of 51 percent Mexican content, as compared to a Ford F-Series pickup made up of 70 percent U.S. and Canadian parts. In 2015, Canada-based suppliers shipped approximately $17 billion worth of vehicle components to the U.S., while the two countries combined shipped $29 billion worth of parts to Mexico, as per the Industria National de Autopartes (Mexican auto parts industry association) and trade data from Industry Canada. Mexico in turn sent more than $61 billion back in parts to its NAFTA trading partners.

Also interesting to note, the U.S. Labor Department says that Mexican, Asian and European companies which produce vehicle parts are a growing share of U.S.-based suppliers, providing nearly 600,000 American jobs.

As compared to the 1960s, the automotive industry today is dynamic and innovative and not surprisingly, the cross-border flow of components has become a tenet of modern manufacturing.

On the Canadian auto front things have changed substantially, as reported by the Canadian Vehicle Manufacturers’ Association: Canada now produces more vehicles than they can sell domestically. In 2015, Canadian plants manufactured over 2.3 million vehicles, of which $57 billion worth were exported for sale in the U.S., equivalent to approximately 85 percent of the vehicles built in Canada – meaning 1.95 million vehicles were exported to the U.S. and 350,000 of the 2.3 million vehicles were sold in Canada. Meanwhile in the same year, Canadians purchased 1.95 million vehicles – the 350,000 made in Canada and 1.6 million imported from the U.S., Mexico and abroad.

The blossoming of the Canadian auto industry has also fostered the development of a successful Canadian auto parts industry with companies such a Magna International Inc., Martinrea International Inc. and Linamar Corp., which are recognized around the world. These companies, along with the auto manufacturers, have become lean and efficient.

In support of improved efficiency due to technological advances, analyst Dennis DesRosiers, of DesRosiers Automotive Consultants Inc., cites the fact that Canada manufactures the same number of vehicles it did in 1993, but with 13,000 fewer workers. But most importantly, integrated supply chains have not only kept costs down for consumers, but have allowed quality, technology and the overall safety of vehicles to be enhanced.

You got Trumped

Aside from the occasional hiccup, the auto industry appears to be working like a well-oiled machine (pun intended)! But before he was even inaugurated, Trump appeared adamant to rewrite the rules governing the North American auto industry – 140 characters at a time. Trump is infamous for taking to Twitter to apply pressure on companies, but few industries have spent as much time in Trump’s crosshairs as the auto sector.

GM, for example, was scolded for importing a model of the Chevy Cruz from Mexico, for which Trump threatened a “big border tax”. During his campaign, Trump also turned up the heat on Ford, which subsequently announced the cancellation of a $1.6 billion plant in Mexico while pledging to create 700 new Michigan-based jobs. Other manufacturers have also altered their plans – all it took was a few casual threats and some pricey tax handouts.

Trump may be resolute about turning back the hands of the globalization clock to the time when “Made in America” meant exactly that. But at what cost?

The return of American manufacturing is a lovely idea in theory. To Trump’s disenfranchised voters, it surely recalls a time when a hard working youngster could get a steady factory job straight out of high school, live a comfortable middle-class life and even retire by age 60. Granted, it may be a hard reality to face, but that America is gone. And no amount of campaign promises will bring it back.

Trump may have been viewed as a progressive presidential candidate, yet a great deal of his economic philosophy remains firmly lodged in yesteryear. The fact of the matter is that the promises made on the campaign trail may not be as simple to fulfill as he made it seem.

Trump can threaten and bully manufacturers to return operations to American soil, but economic reality, as well as a fiduciary duty to stakeholders, will inevitably limit the success of this tactic. Not all can be as it once was. When faced with the prospect of higher wages, a company will naturally opt for the use of more automation in an attempt to at least maintain profits, if not boost them.

We have already seen that technology is a job-eliminating force to be reckoned with that extends far beyond the manufacturing sector, and there are no signs of this trend coming to an end. Automation continues to make inroads, and no wonder: machines make few mistakes, they don’t take vacation or coffee breaks, and they most certainly don’t ask for raises!

Manufacturing is simply not a viable long-term solution for the revival of the middle-class – no matter how good it sounds on the campaign stump. As we have seen, Trump may very well be capable of bullying companies into returning or maintaining jobs on American soil, but with the presence of high-tech machinery and automation, a fundamental disconnect with the American workforce still remains. If he is successful, new jobs will inevitably be of a higher caliber, require more training and even a higher level of education – qualities lacking in the majority of the forgotten men and women whom Trump has vowed to save.

We have yet to see any attempts in tackling this conundrum, let alone an acknowledgement of its existence. Going forward, the U.S. faces two distinct challenges: to help currently displaced workers, and to prepare the labour force for the future waves of change that inevitably await it.

Ultimately, Trump needs to recalibrate his thinking, or his staunchly protectionist stand could very well dismantle decades of progress, and there most certainly will be consequences for all three NAFTA partners and the companies that currently function freely within their borders. Should Trump end the trade agreement in the same vein as TPP – or even make significant modifications – it will likely result in a slow, painful and potentially costly adjustment period. What’s more, it is certainly not clear that the U.S. or Canada would emerge as winners in terms of job growth.

Although we are unclear about most details surrounding the renegotiation of NAFTA or the effects it will have, we are certain that most companies are not willing to make large investments without more clarity on future policy. For the time being, we are hearing Trump tout potential changes to regulations as a bargaining chip, the most obvious of which is the potential for significant tax cuts on corporate earnings.

When it comes to the automakers, Trump and his cabinet are reviewing the stringent fuel economy and emission standards, which require automakers to raise the average fuel efficiency of new fleets to more than 54.5 miles per gallon by 2025. There’s no doubt that the auto manufacturers are spending significantly in order to reach this milestone, but what a potential rollback in fuel economy standards can accomplish – especially longer term – frankly eludes me.

For one, the state of California (the largest car market in the U.S.) has the power to set its own emissions policy. Plus, 11 other states have decided to follow suit, and together they represent 40 percent of the new car market. So as much as Washington may want to relax regulations for the automakers, California remains in the driver’s seat. If GM wants to sell cars in the state, it mandates that they sell more zero-emission vehicles, which in turn requires them to continue to invest in alternative-fuel technologies. A lag in fuel efficiency standards may also affect American automakers’ ability to sell their vehicles in Europe whose standards are even more demanding.

At this point, from what little we know with certainty, you may be asking yourself, how might this all play out for the North American auto industry?

One outcome we can be sure of is that major changes to NAFTA (or its demise) would weaken the auto industry in all three countries, making it unlikely that industry manufacturers would make major new investments in North America. This is probably the biggest flaw in the administration’s argument against free trade, as they effortlessly assume that changes to NAFTA will automatically result in jobs returning to America. There is an entire world of possibilities (literally!), which may make more economic sense. This includes manufacturing in larger trading blocs such as Europe or Asia, any of the other countries with which the U.S. has free trade agreements, or member countries of the World Trade Organization which allow for trade with low, non-punitive tariff rates.

Should Trump succeed in imposing new border restrictions on trade, it is possible that it may lead to some marginal gains for a limited number of workers, although I suspect they would be short lived.

Let me explain: what is more likely to happen with the imposition of American content rules is that U.S. consumers will ultimately pay more for an American vehicle than they do today (as will purchasers in Canada and Mexico). In time, this will not only dampen demand, but diminish the relative competitiveness of American automakers. Vehicles produced by competitors who work within open borders will inevitably become more attractive – just as we saw happen in Canada during the 1960s – even with the addition of a punitive tariff. As a consequence, the number of vehicles produced in the U.S. could fall, and ultimately jobs would be lost.

The auto industry aside, 90 percent of Fortune 500 companies have investments in Mexico, so for U.S. business the potential damage extends far beyond the auto sector. Needless to say, should President Trump decide to take unilateral action, it will almost certainly result in a tit-for-tat retaliation, hurting not only corporate profits but causing a general slowdown of the economy. Not surprisingly, there is little evidence that turning the United States into an island is a recipe for sustained growth. In fact, there are some interesting theories on how protectionism not only slows growth, but also innovation; we have examples such as Argentina to prove it.

Trump and the trade economy

Despite all the talk and speculation surrounding the possibility of renegotiating NAFTA, Trump’s underlying issue with trade appears to be the resulting deficit, and as far as we can tell, his goal is to eliminate it.

Trade should not be a zero-sum game, but rather an exchange of mutual benefit. Contrary to the administration’s belief, you do not come out on top from simply running a trade surplus. Americans are winning everyday from an improved quality of life by having access to higher quality goods at lower prices.

The administration’s nationalistic and protectionist stance is a far cry from Adam Smith’s concept of the invisible hand, which has also typically been the approach of the Republican Party. The invisible hand is an unobservable market force, which in a truly free market without government intervention allows the strongest economy to emerge by bringing supply and demand into balance. This, in turn, maximizes output and efficiency.

Surely, if push came to shove, America could produce the majority of what it needs, but forcing businesses to make poor economic decisions will not only come at the expense of consumers, but as mentioned earlier, over time the country would also be plagued with a lack of innovation, productivity and selection. The U.S. is far better off to engage in trade with countries which can make the products they need for less, and to spend the savings elsewhere, or invest them in pursuit of commercial opportunities which make the most sense for the economy and the nation.

We often hear President Trump complaining that he has “inherited a mess.” With the U.S. having experienced steady job growth, the unemployment rate has worked its way down to 4.8 percent (near nine-year lows), and it has been accompanied by rising wages, improved readings on manufacturing, industrial production and housing. This has resulted in GDP growth of about 2 percent per year since the recovery of the financial crisis.

The economy is far from being in shambles, and you could argue it is quite strong. But given Trump’s rhetoric, he is clearly not satisfied, as his economic agenda not only aims to reduce or eliminate the deficit, but to boost economic growth. The administration is forecasting 3.2 percent annual growth in GDP over the next decade, along with the creation of 25 million new jobs. Meanwhile, America’s economy has not been able to top 3 percent GDP growth in a full year since 2005, when that growth figure may have very well been inflated by the financial wizardry of Wall Street and the euphoric optimism of Main Street, which was liberally borrowing against artificially inflated home values.

Trump and the troubled deficit

If we take a look back at history, to the era of the 80s and 90s, which are often cited as an exemplary time of thriving economic growth, we should not ignore the fact that it was also accompanied by a growing trade deficit.

Actually, America’s trade deficit has been the world’s largest for the last 40 years, and yet America has continued to prosper. In other words, the mere existence of a trade deficit does not mean that wealth is necessarily flowing out of the country. Nor is it a signal that the U.S. has been outnegotiated, or is the loser in the trading game.

Yes, by its very definition, a trade deficit represents an outflow of domestic currency to foreign markets. Perhaps the distaste for the deficit stems from a fear that those dollars will be lost forever? As it turns out, the outflow is more akin to a temporary leakage that is eventually replenished via the capital account in the form of foreign direct investment.

Whether it is an investment in property, plant or equipment, corporate or government debt, these foreign dollars ultimately support U.S. economic activity. Had protectionist measures not permitted those dollars to be used to purchase imports in the first place, many Americans would not have been able to enjoy the subsequent benefits of foreign investments in local factories, research centers, hotel, or shopping malls, etc.

This phenomenon also explains why we have not seen the inverse relationship, which should have occurred between the growth of the trade deficit and job creation, or a decline in output, had a growth in the deficit truly been hazardous to America’s economic health.

In 2015 and 2016, the overall U.S. deficit of both goods and services combined amounted to just over $500 billion. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, Mexico and Canada make up a mere 10 percent of the total U.S. trade deficit for 2015 (8 percent is attributable to Mexico). Japan is the next largest culprit, responsible for 9 percent of the deficit, the European Union is at 20 percent, and China is the largest contributor of all making up 48 percent of the trade deficit. The remaining 13 percent is from a combination of other smaller nations.

At first glance, it seems that Trump’s disruptive political agenda may have been misdirected towards NAFTA when he has some much bigger fish to fry. In fact, Canada rarely finds itself at the top of the U.S. political agenda, let alone the focus of any aggressive policies. We are, of course, part of NAFTA, but luckily Trump and his voters do not seem to be under the impression that Canadians have stolen their jobs. Nonetheless, today we find ourselves in the middle of two nations – the U.S. and Mexico – that have started off a new relationship on the wrong foot, and tensions appear to be building.

Trump has tweeted: “The U.S. has a 60 billion dollar trade deficit with Mexico” and he continued on a second tweet, “It has been a one sided deal from the beginning…with massive numbers of jobs and companies lost.” He may have exaggerated the pact’s effect on manufacturing jobs, but his figures on the Mexican deficit are accurate. The U.S. went from a trade surplus of $1.7 billion prior to NAFTA taking effect, to over $55 billion deficit in 2015 and over $63 billion in 2016.

Currency swings also played a part in aggravating the situation, as the value of the Mexican peso took a plunge after the enactment of the treaty. This made Mexican imports much cheaper and certainly played a role in pricing American products out of the market. And you can point your finger to the auto parts trade as the principal offender for the growing American trade deficit with Mexico, so it is not surprising to see why the automakers have made their way into the Trump limelight.

The U.S. also runs a deficit with Canada ($11.9 billion in 2015), but closer scrutiny of our bilateral trade flows reveals that the import of fossil fuels is the largest factor affecting the trade balance.

Actually, Canada plays an important role in U.S. energy, as “we provide 100 percent of their imported electricity, 85 percent of their imported natural gas, and 43 percent of their imported oil” as per a conversation with former prime minister Brian Mulroney in Policy Magazine (Volume 5 – Issue 1, January/February 2017). If fossil fuels were to be excluded from the trade balance, there would be no deficit with Canada at all. So perhaps America’s problem is not so much the deficit but geography and geology!

On a positive note, thanks in part to America’s shale revolution and NAFTA, the U.S. has reduced its reliance on oil imports from more hostile regions such as the Middle East and Venezuela. And, in turn, Americans benefit from lower gas prices at the pump.

Trade barriers and taxes

So what is it about the deal with Mexico that is unfair towards America? For one, Trump firmly believes that Mexico’s Value Added Tax (VAT) works as a trade barrier, tilting the balance against American manufacturers.

As per the first presidential debate on September 26, 2016, Donald Trump said: “They have a VAT tax. We are on a different system. When we sell into Mexico, there’s a tax. When we sell in, automatically, 16 percent, approximately. But when they sell into us, there’s no tax. It’s a defective agreement. It’s been defective for a long time, many years, but the politicians haven’t done anything about it.”

Trump’s claims are misleading to say the least. VAT is not a tariff, but rather a consumption based tax, common to more than 160 countries around the world, including Mexico and China. It is neither a trade subsidy nor a trade barrier, and Trump’s statement makes it sound like America was duped by Mexico in negotiations, when in fact the VAT has nothing to do with NAFTA.

A VAT is basically the equivalent of a sales tax whereby the consumers of goods and services will all bear the same tax burden – no matter the origin of the product. Meaning that goods produced and sold in Mexico are taxed just the same as the ones that arrived from the United States. In other words, not only is the VAT blind to a product’s origin, but also both local and foreign products are offered to consumers on equal terms.

It is also not entirely accurate to allege that there’s no tax when Mexico sells its products in America, as they are subject to a sales tax in all but five states. And just like the VAT, it applies equally to U.S.-made items and foreign products. Much like Canada’s GST, PST or HST, which are essentially just another form of VAT by another name.

Perhaps confusion arises because of the difference in the two systems. In the U.S. (and Canada) for example, a corporation does not pay sales tax on purchased inputs used in manufacturing, and the entire tax burden applies to the final consumer. As compared to American (and Canadian) manufacturers, inputs purchased for production under the Mexican VAT system are paid no matter the stage of production.

As the VAT is not payable on exported goods, it is only natural that when these items are shipped abroad, that the producer who has paid VAT to its suppliers will in turn receive a credit for the VAT that it will not consequently collect from the foreign purchaser. Once again, this puts the American company and the foreign company on equal footing.

Despite the fact that VAT is not a protectionist policy, and completely kosher under international trade rules, there are a couple of possibilities that have been proposed and discussed by Congress and the White House, which would not only counteract the effects of the administration’s proposed tax cuts, but would also help to pay for the planned border wall with Mexico.

Border adjustment vs. border tax

Speaker of the House Paul Ryan has rolled out a new tax plan which promises to lower rates and significantly simplify the federal tax system. A core component of the plan includes a so-called “border adjustment tax” provision. Under the measure, U.S. imports would be taxed at a rate of 20 percent and would no longer be a deductible expense. Meanwhile, exports would be exempt of tax in order to encourage American companies to move or increase production at home.

If it were to pass, the border fee is meant to raise $1 trillion over the next decade (or approximately $100 billion per year). Congress’s proposed measure would not only affect Mexico, but it would also affect Canada or any other country that exports their products to the U.S.

Perhaps Republicans hoped the proposed measure could satisfy the president’s protectionist urges, but thus far he has been ambivalent and noncommittal and even criticized the border-adjustment as “too complicated”. Instead he has presented a more straightforward 20 percent tax on products imported from south of the border, which could potentially be included as part of a comprehensive tax package passed by Congress. Although we are told this is just one possibility Trump is considering in order for Mexico to pay for the wall.

The administration is adamant that the plan would not only increase U.S. wages, help U.S. businesses and consumers, but also deliver “huge economic benefits.” For the time being, without more transparency on the details of the plan, it remains impossible to substantiate those claims. But despite the obscurity, from what we know to date, one important question remains unanswered: would Mexicans ultimately be footing the bill, or would Americans?

Feeling the pinch

Whether you want to call it a tax or a tariff – or any other descriptive name for that matter – it is ultimately the Americans who will feel the pinch. Companies importing products will not bear the brunt of the added cost and instead will adjust prices upwards: Americans will find themselves paying a premium for a variety of products from groceries to electronics, not to mention favorites like Corona beer and tequila.

Mexico is also a large provider of industrial products used in American manufacturing. The cost of many vehicles would be slated to rise, such as the Kentucky-built Toyota Camry. James Lentz, CEO of Toyota Motor North America, estimates that because approximately a quarter of the vehicle’s parts are sourced from Mexico, a 20 percent tax would raise costs by about $1,000.

Granted, there is the potential for a secondary effect on the Mexican economy. If the import tax results in less sales of Mexican-made products, then consequently there would be an impact on profits, and perhaps eventually over time even on the wages of Mexican workers. As you might imagine, this could, in turn, once again ignite the desire for Mexicans to flee north – or maybe fuel an industry for ladders tall enough to get over the border wall.

Not surprisingly, representatives from the likes of Walmart and Target, as well as those of specialty retailers, have been heading to Capitol Hill to warn of the crippling repercussions of a border tax. Similarly, the Retail Industry Leaders Association (RILA) has launched a national campaign called Americans for Affordable Products to create awareness of the dangers. Despite the honorable effort on the part of Congress, the price of even the most basic and necessary apparel is likely to rise, given that 98 percent of the apparel sold in the U.S. is made abroad.

Grocery bills would also go up. For example, U.S. waters cannot produce enough fish and seafood to satisfy domestic consumption. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, 80 percent of the seafood consumed in the U.S. is imported. Also, items such as coffee, tea, spices, chocolate and bananas cannot be produced in substantial quantity on home soil.

Unless the congressional proposal is amended, the border-adjustment measure unjustly shifts the burden onto bulk importers and retailers – especially onto those which low-income Americans rely on the most. Ultimately, if these businesses cannot deduct the cost of goods as an expense, they would end up paying tax on the full amount of revenue in the already low margin retail game. In essence, paying tax on more than just profits. Who knows, perhaps one day we will see the likes of Target reverse its “Expect more. Pay Less.” slogan!

The proposed border adjustment is also a large issue for the energy sector. Oil refiners would no longer be able to deduct the cost of their largest production input, imported oil.

As such, a corresponding hike in gasoline prices would be expected. According to the Wall Street Journal, in an article titled Border Tax Divides Energy Sector (February 23, 2017), both the American Petroleum Institute and American Fuel and Petrochemical Manufacturers have concluded in internal reports that the price of gasoline would rise by 20 cents or more a gallon.

Meanwhile, large industrial and technology companies such as General Electric, Oracle and Boeing are very much in favour of the proposed border-adjustment proposal. Given their business model, it is completely feasible for them to achieve not paying any taxes at all. In the perfect world, the resulting effects of importing and exporting would cancel each other out, but as it turns out many companies have exposure overwhelmingly on just one side of the equation.

Currency fluctuations

Needless to say, either the congressional border-adjustment proposal or the administration’s tariff-like border tax, are a radical change from the status quo. For those businesses strong enough to survive the shock, it would inevitably take time, and in some cases quite a bit of money to adjust their business models to the new reality. But proponents of change argue that because the terms of trade would be altered, it would lead to a sharp increase in the dollar that would even the playing field.

Let me explain that without a change in the dollar’s value, the likely outcome would be a decrease in imports and a rise in exports, which in turn would cause the trade deficit to narrow. A decline in imports would then reduce demand for foreign currencies to pay for them, and instead there would be an increased demand for dollars. Meaning that the dollar is likely to rise as a result, theoretically enough to offset the proposed tax. So if the dollar’s rise is met with a proportional decline in the Mexican peso or the Canadian dollar for example, then the price of the items in question remains the same. What changes is the purchasing power of the dollars the exporter to the U.S. receives in exchange.

In this scenario, it is true that the burden of the tax would fall on the foreign exporter. Of course, economic theory and reality do not always coincide. There is a real chance that the dollar would not rise fast enough or to a level sufficient to offset the negative impacts.

U.S. companies and individuals alike would also be faced with another challenge should the value of the dollar rise as a response to the proposed border-adjustment tax because it would result in a reduced value of foreign investment. Thus far, estimates predict that the dollar could strengthen by as much as 25 percent.

There is also a matter of legality in Trump’s border tax scenario, which could be in violation of obligations under NAFTA and WTO rules in place to safeguard from protectionist trade policies. Should Trump decide to penalize Mexico with a 20 percent tax, it is likely to be challenged.

The perverse effects of protectionism

To make the administration’s case against a crackdown on trade even more compelling, changes to the U.S. trade deficit calculation are being contemplated.

Reports say the preeminent calculation methodology under consideration would exclude from the export tally any products that enter the country in transit (without being altered), before they are shipped to another country, such as Mexico and Canada. By not including product re-exports into the equation, it would inflate the trade deficit numbers, and perhaps give Trump the ammunition he needs to lift political support for the cause, and as leverage in bilateral negotiations.

Thus far, I have spoken at length of the most obvious drawbacks to protectionism, namely higher prices and restricted selection. The worry is that should Trump move forward with his trade-busting agenda, there are many more perverse effects which may manifest themselves.

By blocking the power of the invisible hand in the free market, the government is picking economic winners and losers, while probably sheltering a few inefficient firms that would have not otherwise survived along the way.

Ultimately, punitive tariffs are aimed at reducing competition by raising the price of foreign goods in order to render locally manufactured ones more attractive. This type of protectionism typically has the effect of temporarily creating jobs for domestic workers, and potentially even boosting wages. This, in turn, increases the incentive of workers to remain low skilled instead of advancing their abilities, education or respective careers. As mentioned earlier, this is a grave problem which the U.S. has yet to tackle successfully.

If the United States closes its borders, other countries will do the same. The temporary increase in jobs would eventually reverse itself as other countries also adopt protectionist measures – let’s not forget that hanging in the balance would be14 million U.S. jobs supported specifically by trade.

Just as the workforce has no incentive to improve, neither does industry when it remains protected. Longer term, the lack of competition eliminates the need to remain on the cutting edge of innovation, and over time product quality declines. Without trade, there is less incentive to move the business forward, and it will evolve slowly and towards obsolescence, eventually producing a more expensive, lower-quality product than that of a foreign competitor operating within truly open borders. Not to be dramatic, but insulation eventually leads to isolation, depressing not only the economy but also civilization.

Additionally, for the “America First” ecosystem to work, consumers need to be willing to pay premium prices, otherwise the system collapses. Americans who voted for Trump in essence agreed to pay up for the benefits of protectionism, but when faced with the real decision of spending actual hard-earned dollars, human nature may push them towards fixing old items instead of buying new ones. Why go out and purchase a new Toyota Camry whose price just jumped by $1,000 when you could save in the short term by upping the maintenance or making minor repairs in order to keep driving your current vehicle for longer?

Under this scenario, there are negative cascading effects. Let’s take, for example, the U.S. farming industry which exports about a third of its total production. If they are no longer shipping their farmed goods abroad, then future crops are likely to be smaller. Farming less land translates into a diminished need for tractors. Fewer tractors means that less steel is needed to build them. And less steel implies fewer steelworkers, and generally a reduced need for labour along every step of the value chain.

At this stage, without a single official policy in place, we are already seeing companies make questionable investment decisions. Thus far, the lack of pushback from America’s largest corporations has been surprising, given that nearly 50 percent of the revenue for companies which make up the S&P 500 comes from abroad.

I can only speculate that the silence is in an effort to appease the president and avoid his Twitter wrath, which often results in reactionary stock price declines. Of course, this is not without favors which the administration will need to deliver, such as tax breaks and deregulation. For the time being, American companies are going along for the ride, knowing that they can survive and even remain profitable (at least for a while) if given generous subsidies while making minimal investments in the business.

Déjà vu?

Ultimately, the repudiation of free trade could resemble something that the U.S. economy has already experienced during the 1930s era of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff.

The Smoot-Hawley Tariff was an attempt to assist Americans in need. Specifically, it was designed to protect local farmers by forcing consumers to buy American-farmed products instead of those coming from Europe. The hope was to shift demand towards American consumption while pushing the burden of the crisis onto foreigners. But by the time the bill made it through Congress, it had expanded to include punitive measures on numerous other imports.

As you would expect, other countries retaliated, which then further contracted the demand for U.S. exports. The result was a competitive trade war and the downward spiral of commerce around the globe.

Although the tariffs did not cause the crisis or the resulting Great Depression, they most certainly exacerbated the situation. Unemployment reached a peak of 25 percent in 1933, and it did not fall below 10 percent for almost a decade until the start of Second World War.

When the war was finally over, 23 nations decided to come together in 1947 in an effort to learn from their mistakes, which resulted in the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). It is now generally understood that retaliatory tactics are also accompanied by catastrophic results, and that the benefits of trade are dispersed and only appreciable over time. Today, the basis of the GATT lives on as the World Trade Organization.

The Trump White House represents a large shift in American ideology, and this populist globalization backlash threatens to undermine the country’s position and influence in the world. Since the Smoot-Hawley era and the end of the Second World War, the U.S. has been exemplary in the promotion of free markets and liberal trade. America’s retreat is a strategic gain for China, which is eager to take over the leadership role in the globalized world.

America is abandoning the world stage as it builds border walls and pulls out of crucial multilateral trade agreements such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). Meanwhile, China is solidifying relationships, increasing connectivity and even promising to uphold the ideals of free trade in the world (even if it practices a mix between free trade and mercantilism) at the World Economic Forum in Davos in January 2017. It is in the process of creating its own economic zone and Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, which now has 52 members. Not surprisingly, the U.S. has refused to join, but membership includes the likes of the United Kingdom, Germany and France. Canada has also applied to take part.

From a strategic standpoint, the U.S. is giving up much of its dominance in Asia, where the notion of American exceptionalism has already begun to fray. Despite the fact that the entire world has benefited from America’s role in trade by instilling the rule of law, if American traditional values recede, it leaves room for China to fashion new trading rules to better suit its needs. It may also make it more difficult for the U.S. to export to Asia, which is still undergoing fast-paced growth, as compared with the rest of the world.

In a speech in Mexico City on May 4, 2017, Bank of Canada Governor Stephen Poloz said President Trump’s protectionist threats were already slowing business growth in Canada and weakening the value of the Canadian dollar. He suggested that part of the solution for both Canada and Mexico would be to revive TPP negotiations – without the involvement of the U.S. – in order to open new markets beyond North America.

Poloz called Trump’s decision in January 2017 to pull out of TPP negotiations “unfortunate”, but pointed out that officials from Canada and 10 other countries had scheduled a meeting in Toronto the weekend of May 6-7, 2017 to discuss the possibility of reviving the TPP negotiations without the U.S.

He noted that Canada has free trade agreements with 15 countries, representing 20 percent of the global economy, and that figure would shoot up when the Canada-European Union trade deal came into force in July 2017.

The future of NAFTA

Needless to say, both Canada and Mexico are important trading partners for America after nearly a quarter century of the North American continent’s three economies being tied together via NAFTA. In 2016, Canada was America’s No. 1 export market for goods (not including services) at a value of $246 billion, followed by Mexico as its No. 2 export market with purchases of $212 billion worth of goods. In his May 4, 2017 speech in Mexico, Bank of Canada Governor Stephen Poloz made a point of saying that in the auto parts sector, Canadian companies have more than 150 plants in the U.S., employing 43,000 Americans. But with Trump’s promises of drastic change, both Canada and Mexico currently find themselves teetering on the precipice of the unknown.

Perhaps Canada initially thought it was in an enviable position as compared with Mexico because we did not appear to be the main target in Trump’s desire to reopen NAFTA. After all, our bilateral trade with the U.S. is almost on equal terms, resulting in only a minor deficit for the U.S. when both trade and services between the two counties are taken into account.

Nonetheless, even after a friendly meeting between President Trump and Prime Minister Justin Trudeau on February 13, 2017, we were not much closer to knowing the fate of the trilateral trade deal and the effect any changes would have on the intricacies of economic integration formed over the last 23 years.

You could say the meeting raised more questions than it answered. Granted, there was no talk of punitive tariffs or the need to rewrite the rules in order for trade between the two countries to become fair – just some “tweaking”, in the president’s words. Phew – but wait, what exactly did he mean by a tweak? The statement was ambiguous and left ample room for interpretation. It is quite possible that one man’s tweak could be another’s complete overhaul!

For the process to begin, the White House needs to provide Congress with a 90-day notice, which was expected to happen sometime in spring 2017, according to Wilbur Ross, the newly appointed U.S. Secretary of Commerce.

The negotiations are expected to take a year to complete, and it could be drawn out as the U.S. government is required by law to consult private sector advisers, as well as lawmakers, throughout the process. Despite the Republican majority in Congress, there are many who do not share the economic nationalistic views of Trump and some members of his cabinet.

The next big question hanging over the renegotiations is what form will they take, as Trump has made his preference for bilateral agreements clear. Whether it will be a two-tiered renegotiation which results in two separate parallel bilateral agreements, or a new trilateral agreement, the challenge lies in the fact that what happens to one party will inevitably have a profound effect on the others. Given the deep-seated economic ties, it would be difficult to merely tweak the agreement for Canada while making significant changes for Mexico –without fully reopening the agreement and starting negotiations anew.

Naturally, each country will aim to look after its own interests, but it is clear that times have changed, and the U.S. is less likely than ever before to budge on its plan to put “America First.” During a March 8, 2017 Bloomberg news interview, Wilbur Ross stated: “They all know they’re going to have to make concessions. The only question is what’s the magnitude, and what’s the form of the concessions.” Given that Canada and Mexico are the weaker trade partners due to their smaller economies and that America is generally less dependent on NAFTA, the U.S. may very well have a leg up in negotiations.

In the meantime, we are faced with many unknowns. Will Trump attempt to put his negotiation skills to the test to broker a completely new deal, or will he simply aim for better terms while maintaining the general infrastructure of NAFTA? Will Trump require Canada and Mexico to essentially “pay” to access the U.S. market? If Mexico is forced out of NAFTA or if the agreement’s rules of origin become more onerous, will we be able to produce Canadian goods that qualify for preferential U.S. treatment? If the administration is not satisfied, will America pull out of the agreement entirely? More importantly, from our Canadian perspective, what would North American trade relations look like without NAFTA?

To tweak or not to tweak?

As per NAFTA Article 2205, the U.S. can pull out of the agreement with a six-month notice. Should it ultimately meet its demise, it would resurrect the pre-existing FTA between Canada and the United States, which originally came into effect in 1988. Canada would be cut off from Mexican inputs, but Mexico would be left with nothing – other than barriers, both physical and economic. Even though Canada and Mexico could theoretically continue on with the pact, it was designed around the U.S. elephant and would make little sense without its participation.

In a December 2016 interview conducted by Policy Magazine Editor L. Ian MacDonald with former prime minister Brian Mulroney, who was responsible for enacting NAFTA, Mulroney referred to it as “an insurance policy.” Stating that “we were concerned that something might happen in the future and we knew that the backbone of our financial success and our economic success as a nation was going to be trade with the United States.”

Yes, Canada would dust off the old documents and have something to fall back upon, but it’s far from a perfect option. The trade deals of today expand their focus beyond just the reduction or elimination of trade barriers and punitive tariffs. NAFTA, for example, pioneered the incorporation of labour and environmental provisions. It also included other improvements over the FTA, such as provisions protecting investors via an independent dispute-settlement process. Today, given the amount of time that has passed and the fundamental changes economies have undergone – such as the advent and rise of e-commerce – the FTA and even NAFTA are due for some much-needed modernization.

Even though the TPP agreement has been abolished, it contained many provisions the U.S. sought from trading partners, and it could be used as a basis for the renegotiation of NAFTA. Canada has the recent pact with the European Union it can use as a guide covering similar provisions, called the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA). Key elements include addressing the digital economy by way of provision of goods and services in the form of data, and minimum labour standards, including a requisite minimum wage, as well as mobility of labour.

Revising the rules of origin will also be a topic of great importance for all parties involved and likely an area in which the U.S. will seek concessions. Rules of origin classify goods by way of how much North American materials they contain in order to qualify for duty-free access. For example, foreign fabric is considered as local content in the clothing industry as long as the item of clothing meets certain conditions such as being cut, sewn or assembled within the trade-free zone. The U.S. is likely to tighten the rules of origin in order to encourage more American production, while Canada will seek to make the rules more comprehensive and straightforward.

Most other concessions America will seek are readily identifiable as the U.S. Trade Representative publishes them annually in the National Trade Estimate Report. Let’s get into some of the specifics.

Perhaps no sector has more to lose than Canada’s dairy industry, which is currently highly protected, with price and supply regulated through quotas. Most U.S. dairy imports are subject to punitive tariffs of up to 300 percent if they surpass quota levels. Under TPP, Canada had already ceded 3 percent of the market, so it is likely that in this coming round of NAFTA negotiations, the U.S. will push for more.

In an April 17, 2017 story written by Caitlin Dewey, The Washington Post indicated that one of the immediate flash points in NAFTA negotiations could be the issue of milk protein concentrates, known as “ultrafiltered milk” which is used as a protein added to cheese.

Dewey reported that ultrafiltered milk was developed after NAFTA’s 1994 enactment and, as a result, did not face high tariffs such as most American dairy products entering Canada’s protected market. The bulk of ultrafiltered milk produced in the U.S. has been shipped to Canada in the 23 years since NAFTA came into force.

However in April 2016, dairy farmers in Ontario dramatically cut their prices on Canadian ultrafiltered milk to undercut U.S. imports of that product, and other provinces were planning to follow suit, according to the newspaper, which described a price war as “a dire threat to U.S. farms.”

“This could certainly become an issue in any attempt to renegotiate NAFTA,” Luis Ribera, an agricultural economist and North American trade expert at Texas A&M, told the Post, which reported in its story that American industry groups, as well as state and congressional politicians were calling on Trump to intervene directly in the dispute, as well as in a similar issue involving Canadian price cuts on skim milk powder.

Similar to the dairy industry, production quotas apply to the poultry and egg markets, which are also likely to be under scrutiny as part of a new NAFTA negotiation. In this scenario, we could see Canada ask for some quid pro quo, as America’s dairy industry benefits from its own protectionist policies.

The topic of Canada’s softwood lumber exports emerged as a flashpoint once again, as it has been a long-running battle between the U.S. and Canada since the early 1980s. Canada owns (by way of provincial and the federal governments) the majority of the lands where Canadian timber is harvested, as compared to the U.S. where lots are normally privately owned. As such, the price of Canadian timber is treated more as an administrative matter, rather than set in a competitive marketplace as it is across the border. As a result, despite the clear and favorable bias of the U.S. house-building industry towards Canadian softwood lumber, the U.S. government would like to impose limits on its import into the U.S. in order to favor American softwood lumber producers. In 2016 alone, the U.S. imported $5.7 billion of Canadian softwood lumber, mainly for residential home building.

Just as the U.S. has a case against Canada’s softwood lumber, Canada has a similar case against American drywall. There is likely no easy resolution in all of the matters mentioned, especially not since Trump’s visit to Wisconsin on April 19, 2017 where he used a speech meant to focus on “buy American, hire American” (before signing a new executive order) to make a sudden and pointed attack on Canadian trade policies. Given that he was in America’s dairyland, Trump was no doubt playing to his constituents by bringing up the “terrible” plight of American dairy farmers. Citing it as “another typical one-sided deal against the United States” he vowed it “won’t be happening for long”, referring to the pricing changes in ultrafiltered milk products that make American imports less competitive.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau calmly made his rebuttal the following day during an interview with Bloomberg Editor-in-Chief John Micklethwait in Toronto by pointing out that “the U.S. has a $400 million dairy surplus with Canada. So it's not Canada that is the challenge here." To which he added: “Let’s not pretend that we are in a global free market when it comes to agriculture. Every country protects, for good reason, its agricultural industries. We have a supply management system that works very well here in Canada. The Americans and other countries choose to subsidize to the tune of hundreds of millions of dollars, if not billions of dollars, their agricultural industries, including their dairy.” And despite the finger pointing, we also know that the troubles of Wisconsin dairy farmers stem from a combination of overproduction and low global milk prices.

On April 21st, Trump doubled down on his previous comments by expanding his list of trade irritants from dairy to lumber and energy. Trump’s fighting words, reminiscent of his protectionist campaign rhetoric, make it clear that Canada is in for much more than just a “tweak” to its trade policies.

To begin with, Trump announced that punitive tariffs of up to 24 percent were to be slapped on Canadian softwood lumber imports beginning April 24, 2017. Softwood lumber products do not fall under NAFTA: over several decades they have been regulated by side agreements, the last of which expired in 2015. So it was known that a new agreement would have to be hammered out between Canada and the U.S. at some point, but Trump used his April visit to Wisconsin as a jumping-off point to fire the first salvo by imposing onerous softwood tariffs, which are, in many cases, retroactive 90 days and will throw smaller Canadian producers into dire economic straits.

As if the softwood tariffs weren’t enough of a shock to the trade relationship, Trump mused on April 26, 2017 that he was thinking of giving the required 180-day notice to terminate NAFTA in its entirety to coincide with his 100th day in office two days later. In an interview with The Washington Post on April 27th, he said: “I was all set to terminate. I looked forward to terminating. I was going to do it.” Trump said he reconsidered after speaking with advisers and with the prime minister of Canada and the president of Mexico, saying: “I like them a lot, both of them. We have a very good relationship. And it’s very hard when you have a relationship, it’s very much something that would not be a nice act. It would not be exactly a friendly act.”

White House insiders told the Post that Trump’s stated intention to terminate NAFTA rattled business executives across America, various agricultural groups, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, state governments, members of Congress, as well as Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross, Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue and Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, who all urged the president to back down. The message was that ending NAFTA would impact negatively all U.S. business and could devastate the U.S. agriculture industry.

The only Trump advisers urging him to keep on his course to cancel NAFTA were trade adviser Peter Navarro and chief strategist Stephen K. Bannon, the Post reported, adding that at the same time two cabinet-level Mexican officials contacted their U.S. counterparts to deliver the blunt message that Mexico would not return to the negotiating table with “a gun to its head” if Trump announced his intention to withdraw from NAFTA. Arturo Sarukhan, a former Mexican ambassador to the United States, described Trump’s threat as a “my way or the highway ambush” from the White House.

Mexican Foreign Minister Luis Videgaray went on to say in an April 27th interview on Mexican television that Canada and Mexico had mapped out a joint strategy for dealing with Trump’s threat to withdraw from NAFTA. “We had the same position,” Videgaray said.

So in reality, Trump had already made up his mind to back down even before he spoke with Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and President Enrique Peña Nieto on Wednesday night, April 26th, the Post reported.

The newspaper gave an interesting anecdote to illustrate how Trump’s advisers, starting with his son-in-law Jared Kushner – who had urged him to back away from cancelling NAFTA – have to play up to him to salve his ego. At one point during The Washington Post interview in the Oval Office on April 27th, Trump, who had already backed down on the issue, turned to Kushner and asked: “Was I ready to terminate NAFTA?”

“Yeah,” Kushner said, before explaining the case he had made to the president: “I said, ‘Look, there’s pluses and minuses to doing it’, and either way he would have ended up in a good place.”

A Canadian Press story published May 8, 2017 in The Toronto Star reported that at 6 p.m. on April 26th Kushner called Katie Telford, Prime Minister Trudeau’s chief of staff, in Ottawa to suggest that it would be good idea for the prime minister to call the president – who was free “right now” – to discuss NAFTA.

The Canadian prime minister followed Kushner’s suggestion and spoke to Trump, as did Mexican president Peña Nieto – although it has not been reported whether Kushner was the White House adviser who triggered the call from the Mexican president. What is known is that Trump spun the calls from the two leaders into what he thought would be a face-saving ploy to explain his change of position about ending NAFTA, saying that Trudeau and Peña Nieto had asked him to back down and that he had acceded to their requests because he likes both men.

Given the mercurial temperament of this president, one wonders how many major changes NAFTA might undergo even if he eventually opts not to pull the plug on the entire agreement. For example, the Trump administration has toyed with the idea of abolishing

NAFTA’s dispute settlement regime (known as NAFTA Chapter 11) – which addresses anti-dumping and countervailing disputes – despite the fact that it seems to have worked in favour of the U.S.

Scott Sinclair of the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives documented the 77 known NAFTA investor-state settlement claims made up to January 1, 2015, which included 35 against Canada, 20 against the U.S. and 22 against Mexico: Canada paid out damages totaling $172 million (Cdn); Mexico paid damages of $204 million (U.S.), while the U.S. had not lost a single NAFTA Chapter 11 case up to that point.

Intellectual property rights are also a continuing priority for America, especially in the realm of pharmaceuticals, as the U.S. has serious concerns regarding certain patent utility requirements that Canada has adopted. Ideally, the U.S. would also like additional co-operation in the fight against counterfeit goods (especially goods shipped from China), as Canadian legislation does not allow for inspection of in-transit goods destined for the U.S. via Canadian ports.

The U.S. may also pursue changes to Canadian personal duty exemptions. For short-term travellers, they are far less generous than those provided to Americans who return from travel in Canada. U.S. retailers have raised concerns on the diminishing effects of spending when on their side of the border. The same goes for personal imports of U.S. wines and spirits, which are subject to high provincial taxes and duties.

On a similar note, given the rise of American e-commerce companies, the U.S. would like to see an increase in Canada’s de minimis threshold (DMT). It is the value below which shipments from abroad are exempt from duties and taxes and customs processes, and it is currently set at a mere $20. As you might imagine, it was set in the pre-digital universe nearly three decades ago. It is also the lowest DMT in the world, as compared to the U.S., which has the highest at $800.

Canada spends a great deal of money and resources to collect the tax and inspect these small parcels at the border – it does not even come close to covering the cost of doing so. A C.D. Howe Institute trade and international policy briefing entitled “Rights of Passage: The Economic Effects of Raising the de minimis Threshold in Canada” (published in June 2016 by Christine McDaniel, Simon Schropp and Olim Latipov), reveals that for the government to collect $39 million in additional revenues on these small value shipments, it comes at a cost of $166 million. Needless to say, this is a money-losing endeavour where both countries could stand to benefit if changes were made.

The U.S. is also weary of the support the provincial and federal governments provide to Canada’s aerospace industry – namely Bombardier. Whether it be in the form of the direct aid the company has received or whether it is masked under the veil of research and development grants, or the commercial loans the government is providing to potential purchasers of their CSeries aircraft and the additional credits they receive when the aircraft is sold in the U.S. market – the U.S. views these as subsidies working against American-made products. Meanwhile, Canada, in return, would likely solicit the opportunity to participate in U.S. government procurement projects. This would require the relaxation of local content rules, which in most cases preclude Canadian companies from even participating in the bidding process.

Other than the reciprocal requests briefly outlined above, Canada may also want to solidify measures to prevent a great unraveling of the fully integrated auto-manufacturing sector. Canada could also seek an update to the list of professionals who qualify for temporary entry to the U.S., something they were not able to achieve in TPP negotiations. But the biggest ask would be for the U.S. to open up its agricultural sector, namely the sugar industry, which is heavily protected and currently excluded from NAFTA.

Opportunity pipeline

Despite the concessions and the potential downside of reopening negotiations, there is one large potential opportunity for Canada and it comes in the form of the Keystone XL pipeline, as part of Trump’s plan for energy independence.

The Obama administration had originally vetoed the project, but Trump encouraged TransCanada Corp., the Keystone pipeline builder, to reapply for a permit. The project was finally given a presidential approval on March 24, 2017. If completed, the pipeline would be capable of sending up to 830,000 barrels a day from Canada’s Alberta oil sands to America’s refiners on the Gulf Coast. It also has the potential to create thousands of jobs for Canadians, particularly where they are most needed – in Western Canada.

Despite Trump’s blessings, the project still faces numerous hurdles, namely state-level approvals are needed in Nebraska and South Dakota, and there is continued opposition from environmentalists. There’s also the matter of Trump’s pledge for the exclusive use of American steel in its construction, as well as his expressed desire for a piece of the profits. It is now clear that the U.S. steel promise is unlikely to be fulfilled as the pipeline was already under construction and the materials were previously acquired, although this will be a requirement for new projects. As for the profit-sharing, it appears he has also backed away from pervious comments that would have otherwise been a clear violation of our capitalistic system.

With the arrival of the pipeline also comes consequences for the oil market. Keystone may very well impact oil production in the U.S. and, as such, the price of oil. And if oil prices are depressed, that could, in turn, make expensive oil sands projects – whose heavy crude sells at a discount to the light sweet variety – less viable than they already are today.